Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Monetary Policy rePort

February 23, 2018

For use at 11:00 a.m., EST

February 23, 2018

Letter of transmittaL

B G

F R S

Washington, D.C., February 23, 2018

T P S

T S H R

The Board of Governors is pleased to submit its Monetary Policy Report pursuant to

section 2B of the Federal Reserve Act.

Sincerely,

Jerome H. Powell, Chairman

Adopted effective January24, 2012; as amended effective January30, 2018

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is rmly committed to fullling its statutory

mandate from the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate

long-term interest rates. The Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public

as clearly as possible. Such clarity facilitates well-informed decisionmaking by households and

businesses, reduces economic and nancial uncertainty, increases the eectiveness of monetary

policy, and enhances transparency and accountability, which are essential in a democratic society.

Ination, employment, and long-term interest rates uctuate over time in response to economic and

nancial disturbances. Moreover, monetary policy actions tend to inuence economic activity and

prices with a lag. Therefore, the Committee’s policy decisions reect its longer-run goals, its medium-

term outlook, and its assessments of the balance of risks, including risks to the nancial system that

could impede the attainment of the Committee’s goals.

The ination rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the

Committee has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for ination. The Committee rearms its

judgment that ination at the rate of 2percent, as measured by the annual change in the price

index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the

Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate. The Committee would be concerned if ination were running

persistently above or below this objective. Communicating this symmetric ination goal clearly to the

public helps keep longer-term ination expectations rmly anchored, thereby fostering price stability

and moderate long-term interest rates and enhancing the Committee’s ability to promote maximum

employment in the face of signicant economic disturbances. The maximum level of employment

is largely determined by nonmonetary factors that aect the structure and dynamics of the labor

market. These factors may change over time and may not be directly measurable. Consequently,

it would not be appropriate to specify a xed goal for employment; rather, the Committee’s policy

decisions must be informed by assessments of the maximum level of employment, recognizing that

such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The Committee considers a

wide range of indicators in making these assessments. Information about Committee participants’

estimates of the longer-run normal rates of output growth and unemployment is published four

times per year in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections. For example, in the most

recent projections, the median of FOMC participants’ estimates of the longer-run normal rate of

unemployment was 4.6percent.

In setting monetary policy, the Committee seeks to mitigate deviations of ination from its

longer-run goal and deviations of employment from the Committee’s assessments of its maximum

level. These objectives are generally complementary. However, under circumstances in which the

Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it follows a balanced approach in

promoting them, taking into account the magnitude of the deviations and the potentially dierent

time horizons over which employment and ination are projected to return to levels judged

consistent with its mandate.

The Committee intends to rearm these principles and to make adjustments as appropriate at its

annual organizational meeting each January.

statement on Longer-run goaLs and monetary PoLicy strategy

Note: This report reects information that was publicly available as of noon EST on February 22, 2018.

Unless otherwise stated, the time series in the gures extend through, for daily data, February21, 2018; for monthly

data, January2018; and, for quarterly data, 2017:Q4. In bar charts, except as noted, the change for a given period is

measured to its nal quarter from the nal quarter of the preceding period.

For gures 15 and 33, note that the S&P 500 Index and the Dow Jones Bank Index are products of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its afliates and

have been licensed for use by the Board. Copyright © 2018 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its afliates. All rights reserved.

Redistribution, reproduction, and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. For more

information on any of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC’s indices please visit www.spdji.com. S&P® is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial

Services LLC, and Dow Jones® is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC. Neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark

Holdings LLC, their afliates nor their third party licensors make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the ability of any index to

accurately represent the asset class or market sector that it purports to represent, and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings

LLC, their afliates nor their third party licensors shall have any liability for any errors, omissions, or interruptions of any index or the data included therein.

contents

Summary ..................................................1

Economic and Financial Developments ......................................... 1

Monetary Policy ........................................................... 2

Special Topics ............................................................. 2

Part 1: Recent Economic and Financial Developments ................ 5

Domestic Developments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Financial Developments .................................................... 21

International Developments ................................................. 27

Part 2: Monetary Policy ....................................... 31

Part 3: Summary of Economic Projections ......................... 39

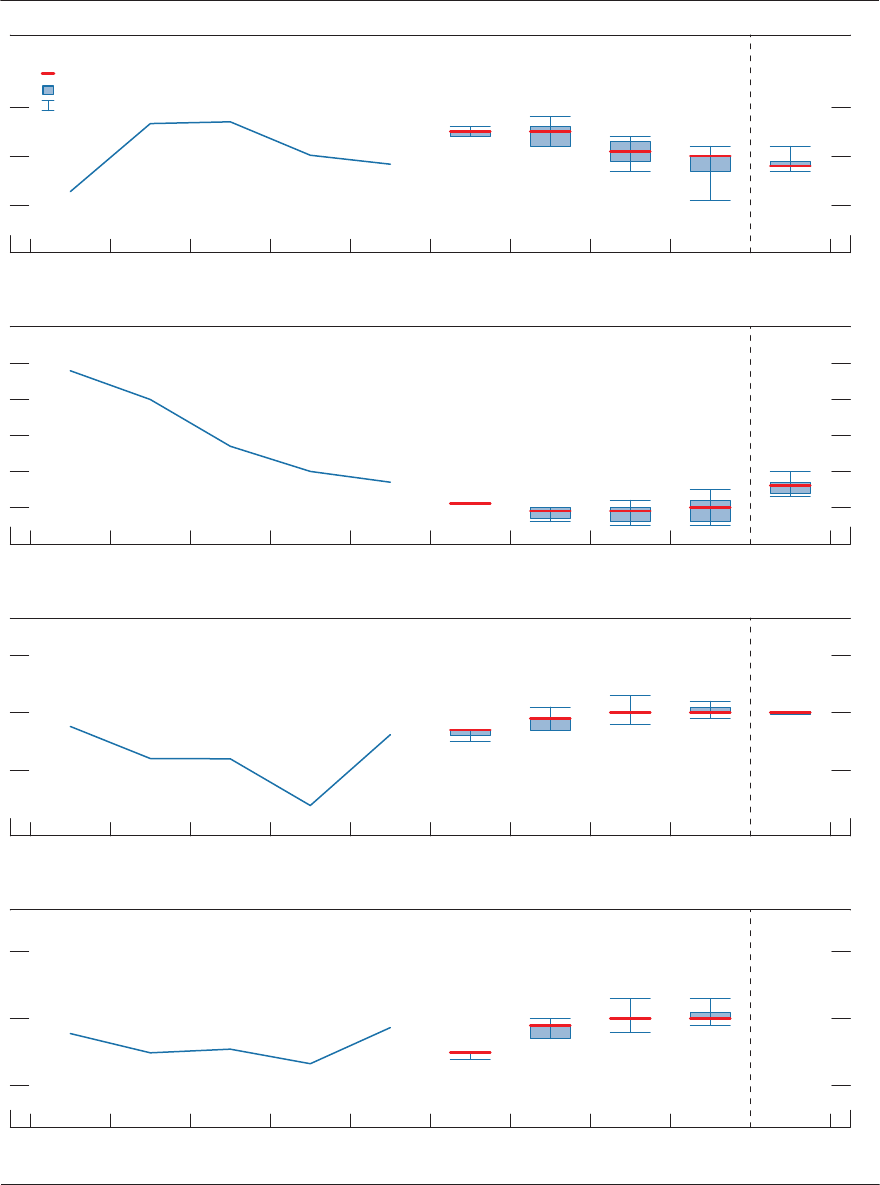

The Outlook for Economic Activity ............................................ 40

The Outlook for Ination ................................................... 45

Appropriate Monetary Policy ................................................ 45

Uncertainty and Risks ...................................................... 45

Abbreviations ..............................................55

List of Boxes

How Tight Is the Labor Market? ................................................ 8

Low Ination in the Advanced Economies ...................................... 14

Developments Related to Financial Stability ..................................... 24

Monetary Policy Rules and Their Role in the Federal Reserve’s Policy Process ............ 35

Forecast Uncertainty ....................................................... 54

1

summary

Economic activity increased at a solid pace

over the second half of 2017, and the labor

market continued to strengthen. Measured

on a 12-month basis, ination has remained

below the Federal Open Market Committee’s

(FOMC) longer-run objective of 2percent.

The FOMC raised the target range for the

federal funds rate twice in the rst half of

2017, resulting in a range of 1 to 1¼percent

by the end of its June meeting. With the

federal funds rate rising toward more normal

levels, at its September meeting, the FOMC

decided to initiate a program of gradually

and predictably reducing the size of its

balance sheet. At its meeting in December,

the Committee judged that current and

prospective economic conditions called for

a further increase in the target range for the

federal funds rate, to 1¼ to 1½percent.

Economic and Financial

Developments

The labor market. The labor market has

continued to strengthen since the middle of

last year. Payroll employment has posted solid

gains, averaging 182,000 per month in the

seven months starting in July2017, about the

same as the average pace in the rst half of

2017. Although net job creation last year was

slightly slower than in 2016, it has remained

considerably faster than what is needed,

on average, to absorb new entrants into the

labor force. The unemployment rate declined

from 4.3percent in June to 4.1percent in

January—somewhat below the median of

FOMC participants’ estimates of its longer-

run normal level. Other measures of labor

utilization also suggest that the labor market

has tightened since last summer. Nonetheless,

wage growth has been moderate, likely held

down in part by the weak pace of productivity

growth in recent years.

Ination. Consumer price ination has

remained below the FOMC’s longer-run

objective of 2percent. The price index for

personal consumption expenditures increased

1.7percent over the 12 months ending in

December2017, about the same as in 2016.

The 12-month measure of ination that

excludes food and energy items (so-called

core ination), which historically has been

a better indicator of where overall ination

will be in the future than the headline gure,

was 1.5percent in December—0.4percentage

point lower than it had been one year earlier.

However, monthly readings on core ination

were somewhat higher during the last few

months of 2017 than earlier in the year.

Measures of longer-run ination expectations

have, on balance, been generally stable,

although some measures remain low by

historical standards.

Economic growth. Real gross domestic product

(GDP) is reported to have increased at an

annual rate of nearly 3percent in the second

half of 2017 after rising slightly more than

2percent in the rst half. Consumer spending

expanded at a solid rate in the second half,

supported by job gains, rising household

wealth, and favorable consumer sentiment.

Business investment growth was robust, and

indicators of business sentiment have been

strong. The housing market has continued

to improve slowly. Foreign activity remained

solid and the dollar depreciated further in the

second half, but net exports subtracted from

real U.S. GDP growth as imports of consumer

and capital goods surged late in the year.

Financial conditions. Financial conditions

for businesses and households have

eased on balance since the middle of

2017 amid an improving global growth

outlook. Notwithstanding nancial market

developments in recent weeks, broad measures

of equity prices are higher, and spreads of

yields on corporate bonds over those of

comparable-maturity Treasury securities have

narrowed. Most types of consumer loans

2 SUMMARY

remained widely available, though credit

was still dicult to access in credit card and

mortgage markets for borrowers with low

credit scores or harder-to-document incomes.

Longer-term nominal Treasury yields and

mortgage rates have moved up on net. The

dollar depreciated, on average, against the

currencies of our trading partners. In foreign

nancial markets, equity prices generally

increased in the second half of 2017, and most

of those indexes remain higher, on net, despite

recent declines. Most longer-term yields rose

noticeably.

Financial stability. Vulnerabilities in the U.S.

nancial system are judged to be moderate on

balance. Valuation pressures continue to be

elevated across a range of asset classes even

after taking into account the current level

of Treasury yields and the expectation that

the reduction in corporate tax rates should

generate an increase in after-tax earnings.

Leverage in the nonnancial business sector

has remained high, and net issuance of risky

debt has climbed in recent months. In contrast,

leverage in the household sector has remained

at a relatively low level, and household debt

in recent years has expanded only about in

line with nominal income. Moreover, U.S.

banks are well capitalized and have signicant

liquidity buers.

Monetary Policy

Interest rate policy. The FOMC continued

to gradually increase the target range for the

federal funds rate. After having raised it twice

in the rst half of 2017, the Committee raised

the target range for the federal funds rate

again in December, bringing it to the current

range of 1¼ to 1½percent. The decision

to increase the target range for the federal

funds rate reected the solid performance of

the economy. Even with this rate increase,

the stance of monetary policy remains

accommodative, thereby supporting strong

labor market conditions and a sustained return

to 2percent ination.

The FOMC expects that, with further gradual

adjustments in the stance of monetary policy,

economic activity will expand at a moderate

pace and labor market conditions will remain

strong. Ination on a 12-month basis is

expected to move up this year and to stabilize

around the Committee’s 2percent objective

over the next few years. The federal funds

rate is likely to remain, for some time, below

levels that are expected to prevail in the longer

run. Consistent with this outlook, in the most

recent Summary of Economic Projections

(SEP), which was compiled at the time of the

December FOMC meeting, the median of

participants’ assessments for the appropriate

level of the federal funds rate through the end

of 2019 remains below the median projection

for its longer-run level. (The December SEP is

presented in Part 3 of this report.) However,

as the Committee has continued to emphasize,

the actual path of the federal funds rate will

depend on the economic outlook as informed

by incoming data. In particular, with ination

having persistently run below the 2percent

longer-run objective, the Committee will

carefully monitor actual and expected ination

developments relative to its symmetric

ination goal.

Balance sheet policy. In the second half of

2017, the Committee initiated the balance

sheet normalization program that is described

in the Addendum to the Policy Normalization

Principles and Plans the Committee issued in

June.

1

Specically, since October, the Federal

Reserve has been gradually reducing its

holdings of Treasury and agency securities

by decreasing the reinvestment of principal

payments it receives from these securities.

Special Topics

How tight is the labor market? Although

there is no way to know with precision, the

1. The June addendum is available on the Board’s

website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/

files/FOMC_PolicyNormalization.20170613.pdf.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2018 3

labor market appears to be near or a little

beyond full employment at present. The

unemployment rate is somewhat below most

estimates of its longer-run normal rate, and

the labor force participation rate is relatively

close to many estimates of its trend. Although

employers report having more diculties

nding qualied workers, hiring continues

apace, and serious labor shortages would likely

have brought about larger wage increases than

have been evident to date. (See the box “How

Tight Is the Labor Market?” in Part1.)

Low global ination. Ination has generally

come in below central banks’ targets in the

advanced economies for several years now.

Resource slack and commodity prices—as

well as, for the United States, movements in

the U.S. dollar—appear to explain ination’s

behavior fairly well. But our understanding is

imperfect, and other, possibly more persistent,

factors may be at work. Resource slack at

home and abroad might be greater than it

appears to be, or ination expectations could

be lower than suggested by the available

indicators. Moreover, some observers have

pointed to increased competition from online

retailers or international developments—

such as global economic slack or the

integration of emerging economies into the

world economy—as contributing to lower

ination. Policymakers remain attentive

to the possibility of such forces leading to

continued low ination; they also are watchful

regarding the opposite risk of ination moving

undesirably high. (See the box “Low Inflation

in the Advanced Economies” in Part 1.)

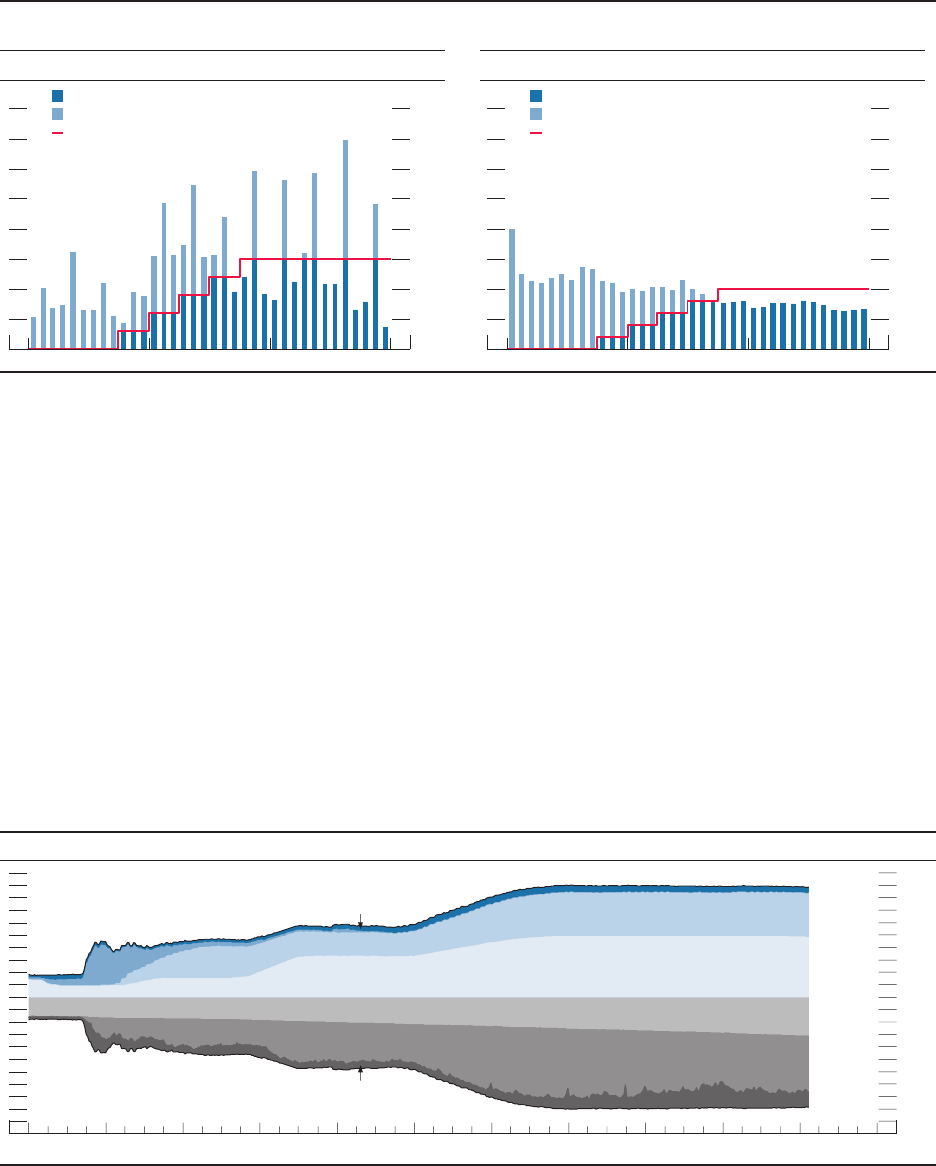

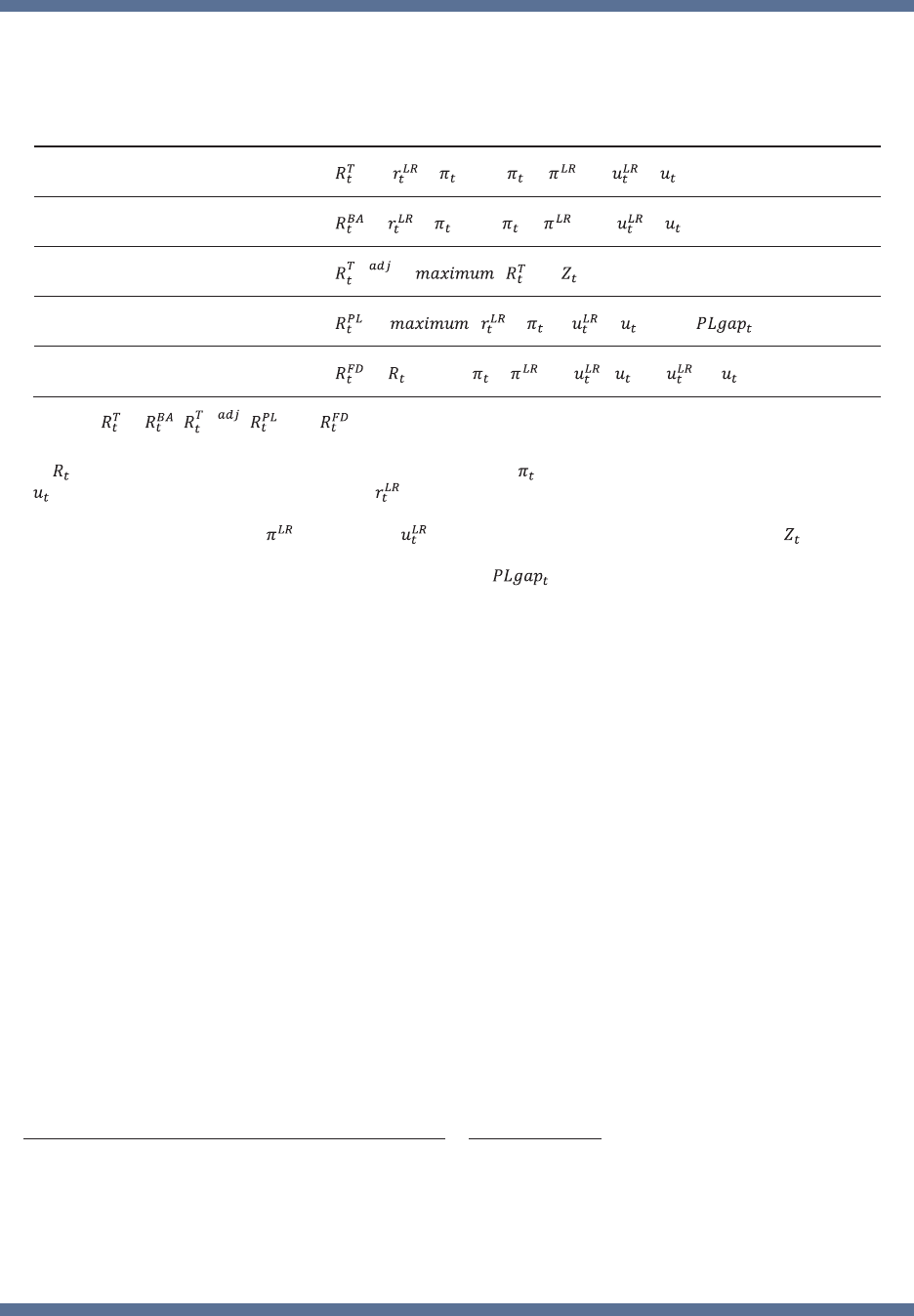

Monetary policy rules. Monetary policymakers

consider a wide range of information on

current economic conditions and the outlook

before deciding on a policy stance they deem

most likely to foster the FOMC’s statutory

mandate of maximum employment and stable

prices. They also routinely consult monetary

policy rules that connect prescriptions for the

policy interest rate with variables associated

with the dual mandate. The use of such rules

requires careful judgments about the choice

and measurement of the inputs into these

rules as well as the implications of the many

considerations these rules do not take into

account. (See the box “Monetary Policy Rules

and Their Role in the Federal Reserve’s Policy

Process” in Part 2.)

5

Domestic Developments

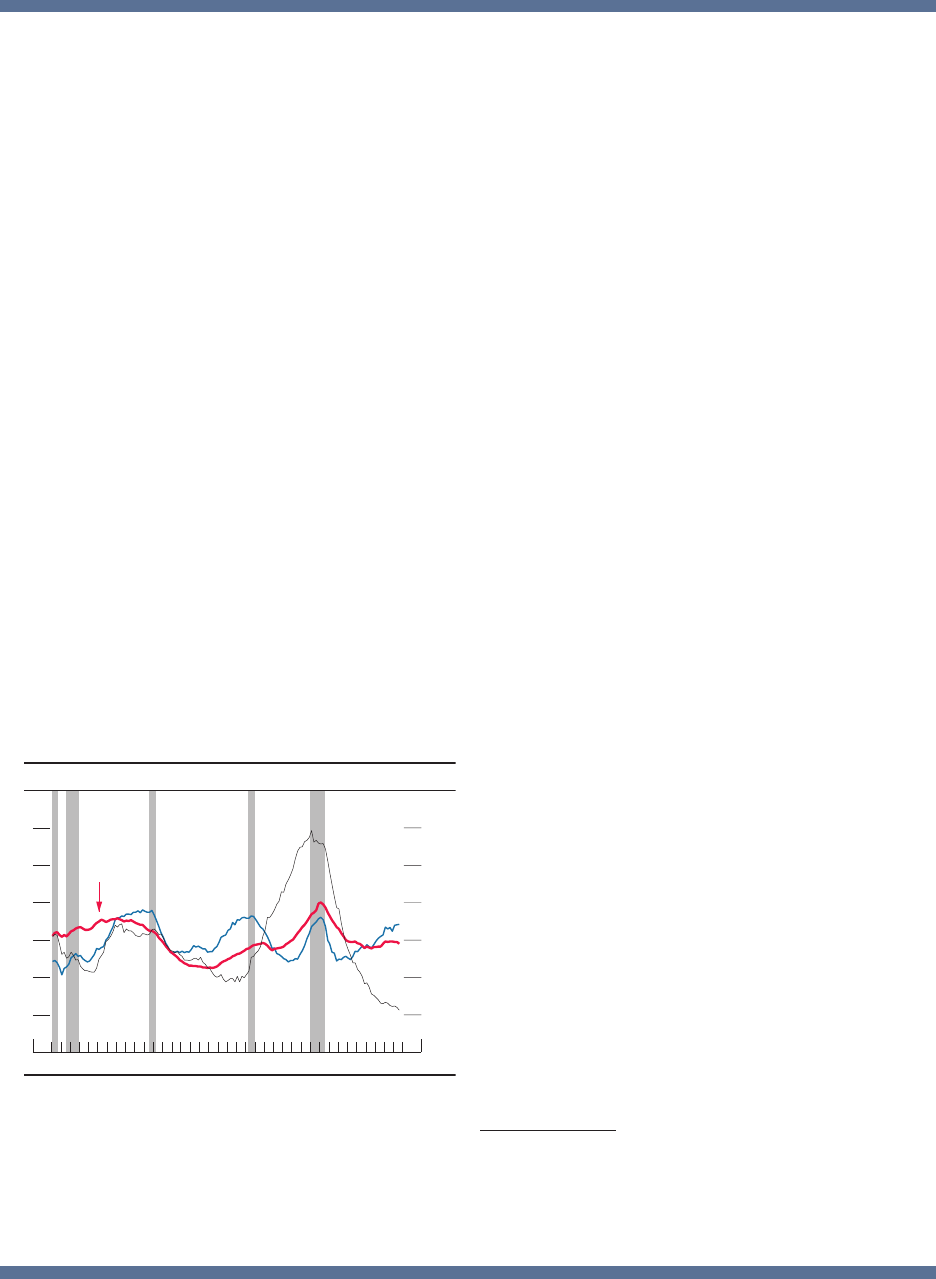

The labor market strengthened further

during the second half of 2017 and early

this year

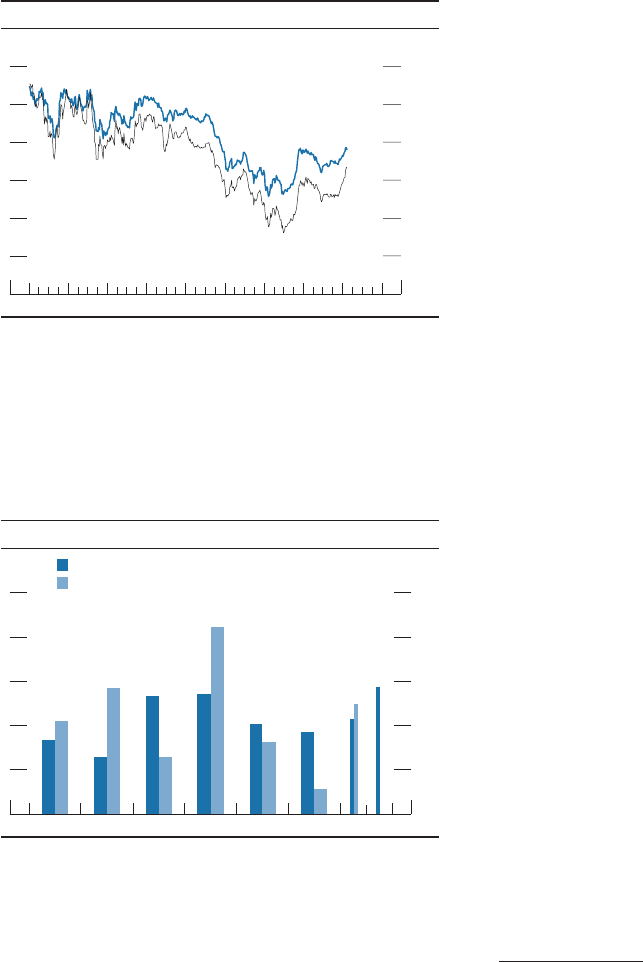

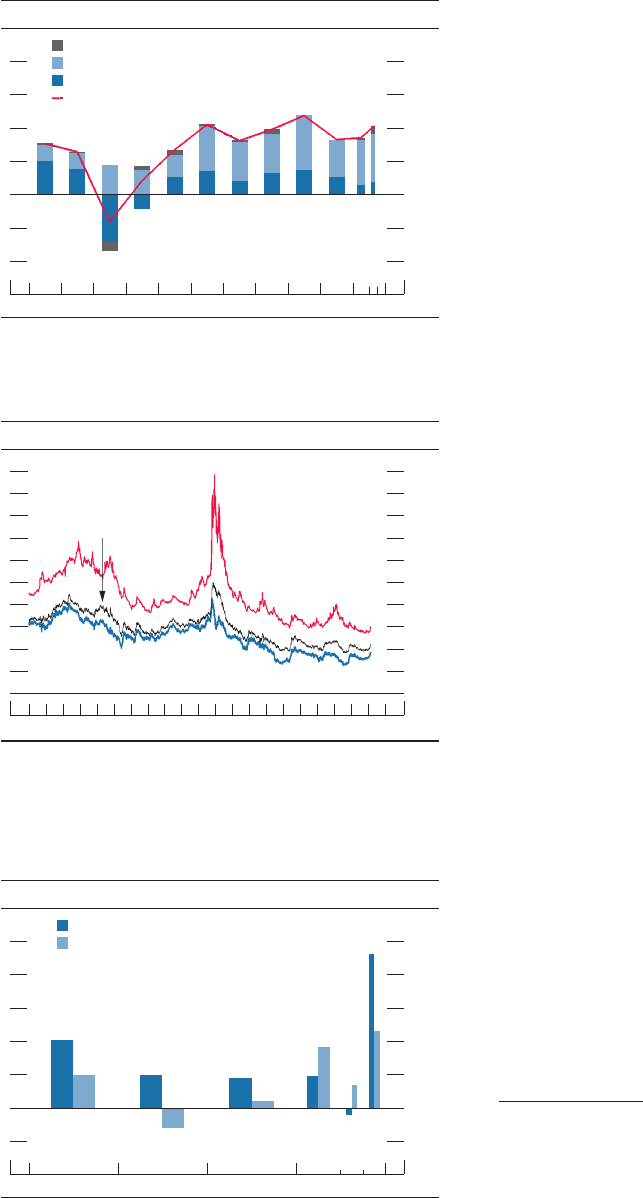

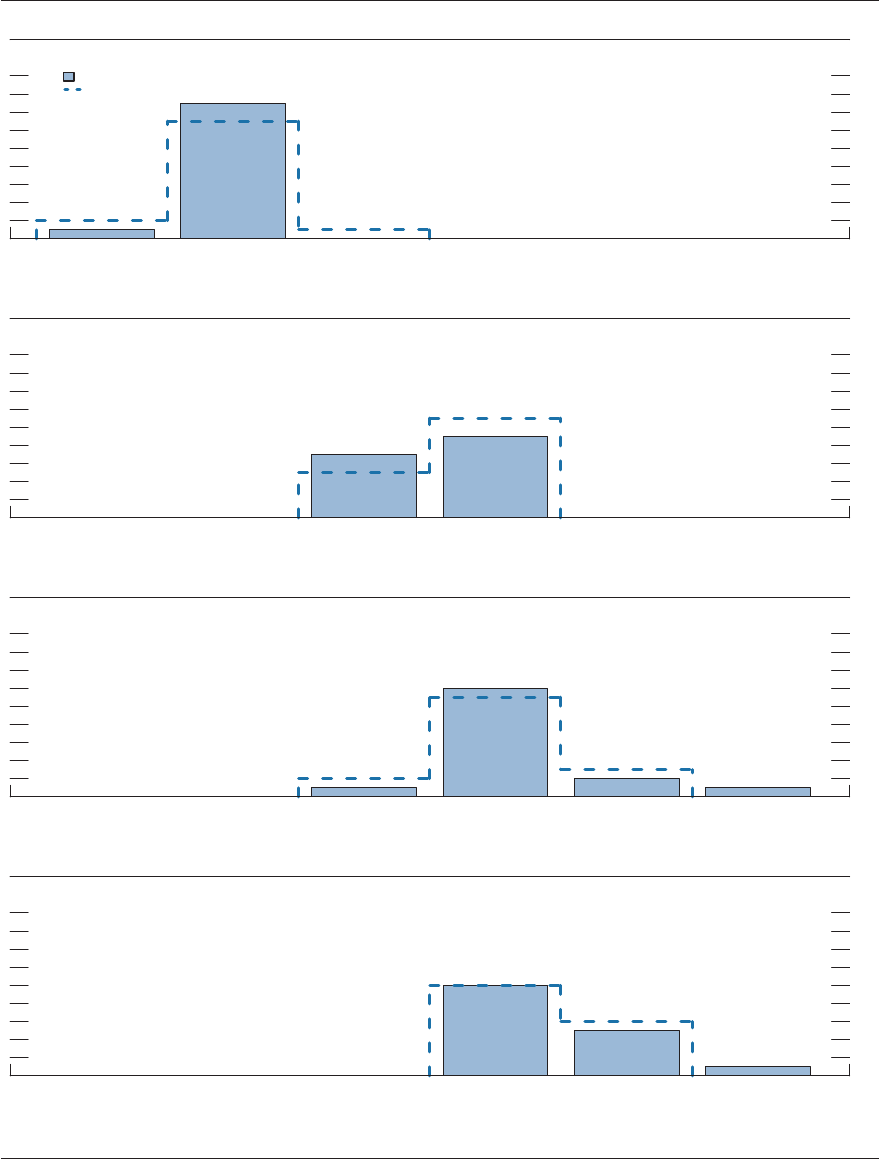

Payroll employment has continued to post

solid gains, averaging 182,000 per month

in the seven months starting in July2017,

about the same pace as in the rst half of

2017.

2

Although net job creation last year was

slightly slower than in 2016, it has remained

considerably faster than what is needed, on

average, to absorb new entrants to the labor

force and is therefore consistent with the

view that the labor market has strengthened

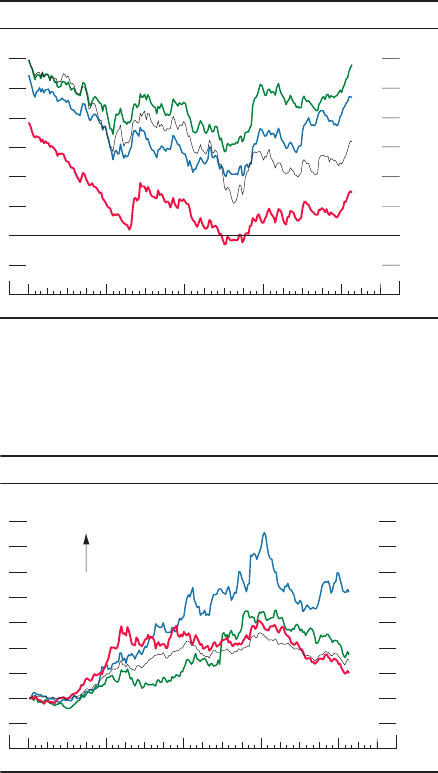

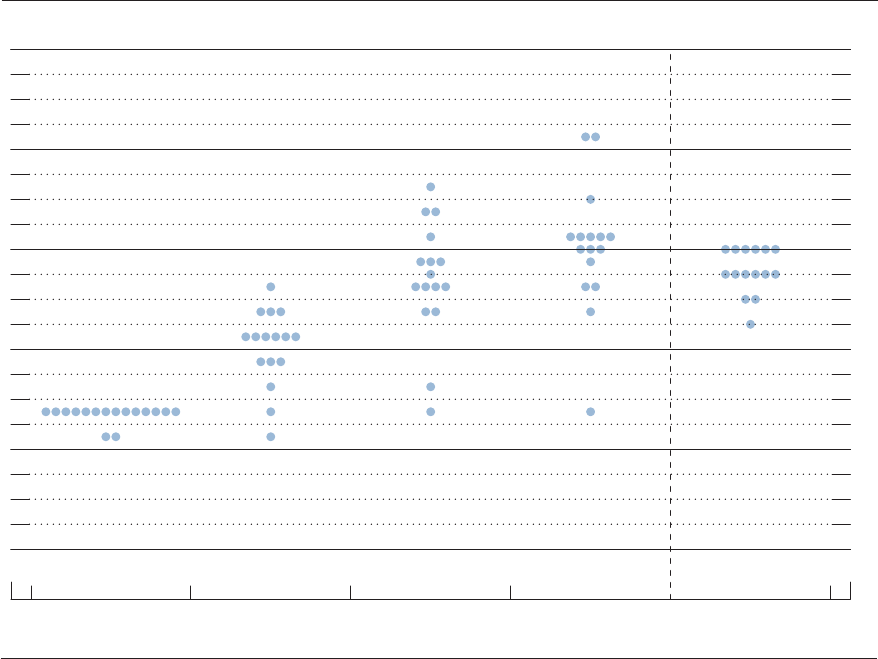

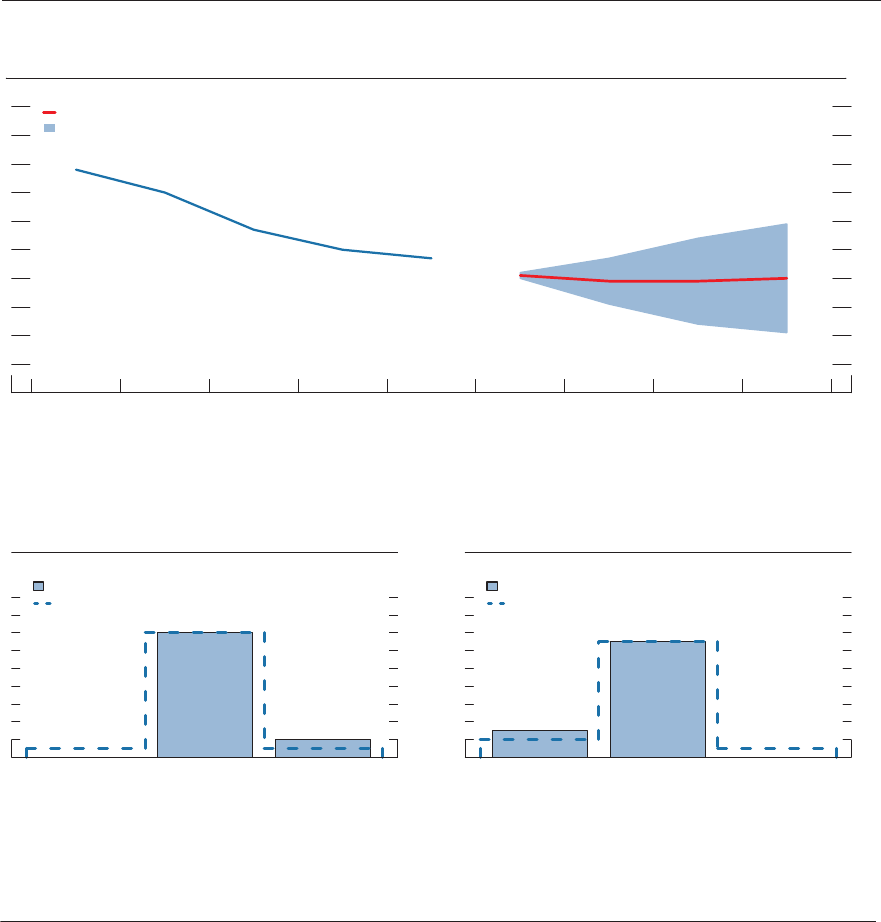

further (gure1). The strength of the labor

market is also evident in the decline in the

unemployment rate to 4.1percent in January,

¼percentage point below its level in June2017

and about ½percentage point below the

median of Federal Open Market Committee

(FOMC) participants’ estimates of its longer-

run normal level (gure2).

Other indicators also suggest that labor

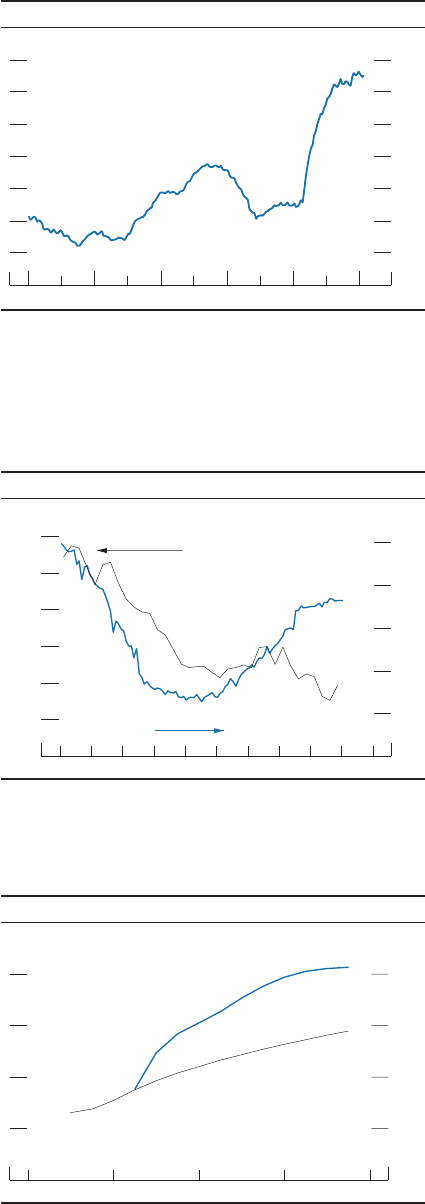

market conditions have continued to tighten.

The labor force participation rate (LFPR)—

that is, the share of adults either working or

actively looking for work—was 62.7percent

in January. The LFPR is little changed, on

net, since early 2014 (gure3). However, the

average age of the population is continuing

to increase. In particular, the members of the

baby-boom cohort increasingly are moving

into their retirement years, a time when labor

force participation typically is low. That

development implies that a sustained period

in which the demand for and supply of labor

were in balance would be associated with a

downward trend in the overall participation

rate. Accordingly, the at prole of the LFPR

2. The hurricanes that struck the United States during

the second half of last year caused substantial variation

in the month-to-month pattern of job gains, but the

average performance over the period as a whole was

probably substantially unaected.

during the past few years is consistent with

an overall picture of improving labor market

conditions. In line with this perspective, the

LFPR for individuals aged 25 to 54—which is

much less sensitive to population aging—has

been rising since 2015. The employment-

to-population ratio for individuals 16 and

older—that is, the share of people who are

working—was 60.1percent in January and has

been increasing since 2011; this gain primarily

reects the decline in the unemployment rate.

(The box “How Tight Is the Labor Market?”

describes the available measures of labor

market slack in more detail.)

Other indicators are also consistent with

continuing strong labor demand. The

number of people ling initial claims for

unemployment insurance has remained near

its lowest level in decades.

3

As reported in the

Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, the

rate of job openings remained elevated in the

second half of 2017, while the rate of layos

remained low. In addition, the rate of quits

stayed high, an indication that workers are able

to obtain a new job when they seek one.

3. Initial claims jumped in the fall of 2017 as a

consequence of disruptions from the hurricanes and then

returned to a low level.

Total nonfarm

800

600

400

200

+

_

0

200

400

Thousands of jobs

2018201720162015201420132012201120102009

1. Net change in payroll employment

3-month moving averages

Private

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

Part 1

recent economic and financiaL deveLoPments

6 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Employment-to-population ratio

Prime-age labor force participation rate

56

58

60

62

64

66

68

Percent

80

81

82

83

84

85

20182014201020062002

3. Labor force participation rates and

employment-to-population ratio

Percent

Labor force participation rate

NOTE

: The data are monthly. The prime-age labor force participation

rate

is a percentage of the population aged 25 to 54. The labor force

participation

rate and the employment-to-population ratio are percentages of the

population

aged 16 and over.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

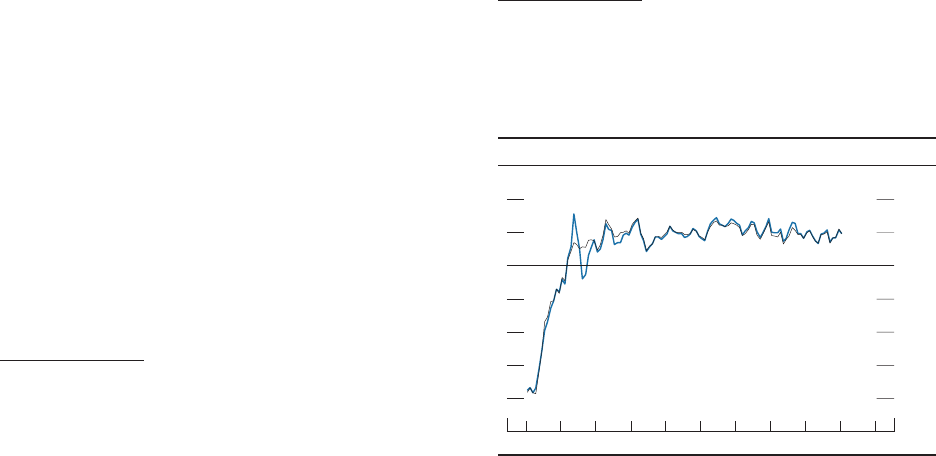

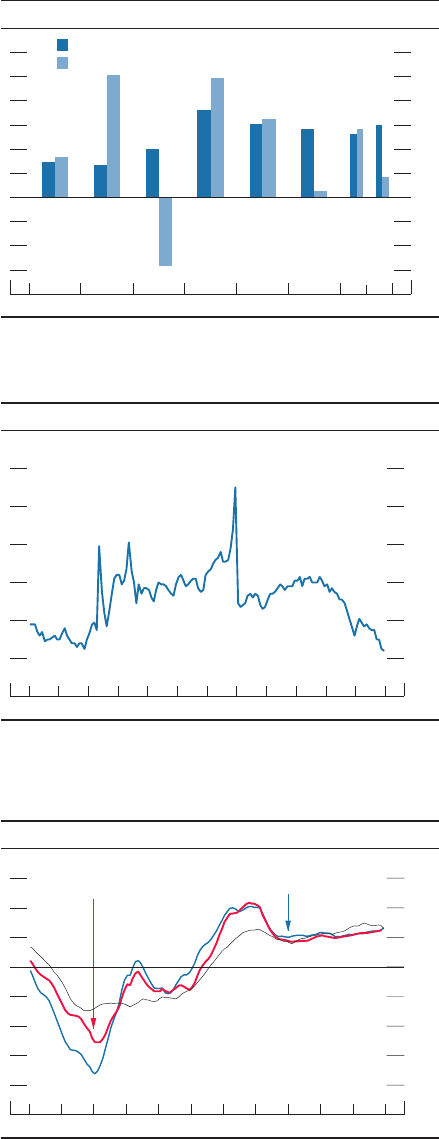

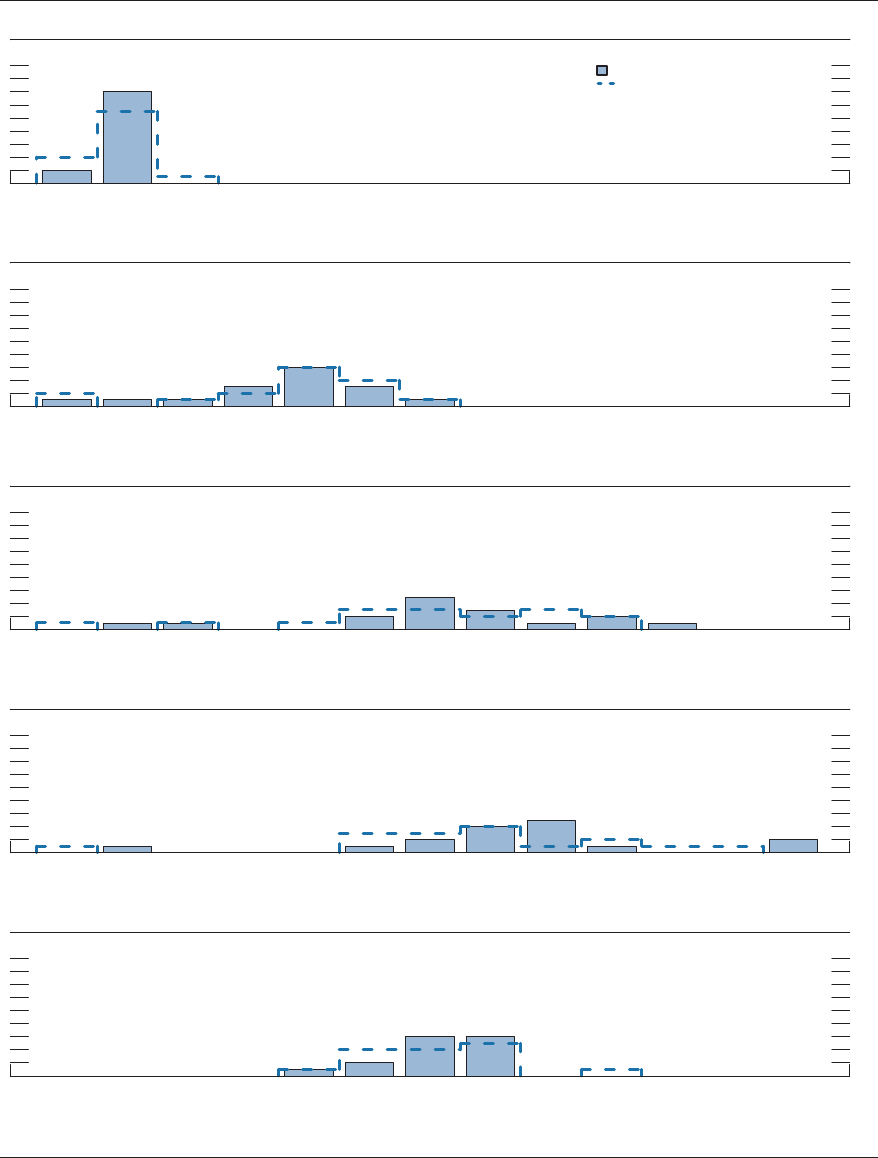

Unemployment rates have declined across

demographic groups, but unemployment

remains high for some groups

Unemployment rates have trended downward

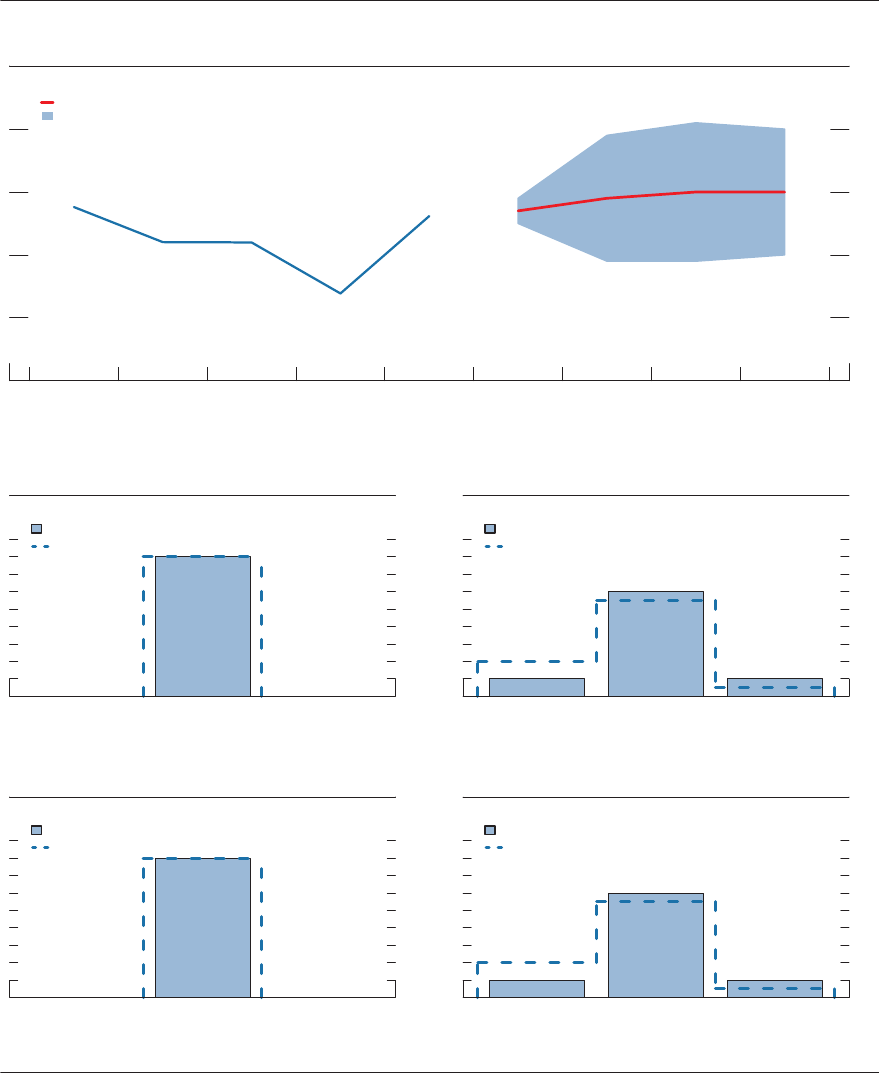

across racial and ethnic groups (gure4). The

decline in the unemployment rate for blacks or

African Americans over the past few years has

been particularly notable. This broad pattern

is typical: The unemployment rates for blacks

and Hispanics tend to rise considerably more

than the rates for whites and Asians during

recessions, and then they decline more rapidly

during expansions. Yet even with the recent

narrowing, the disparities in unemployment

rates across demographic groups remain

substantial and largely the same as before the

recession. The unemployment rate for whites

has averaged 3.7percent since the middle of

2017 and the rate for Asians has been about

3.3percent, while the unemployment rates for

Hispanics or Latinos (5.0percent) and blacks

(7.3percent) have been substantially higher.

In addition, the labor force participation

rates for blacks, Hispanics, and Asians have

generally been lower than those for whites

of the same age group. As the labor market

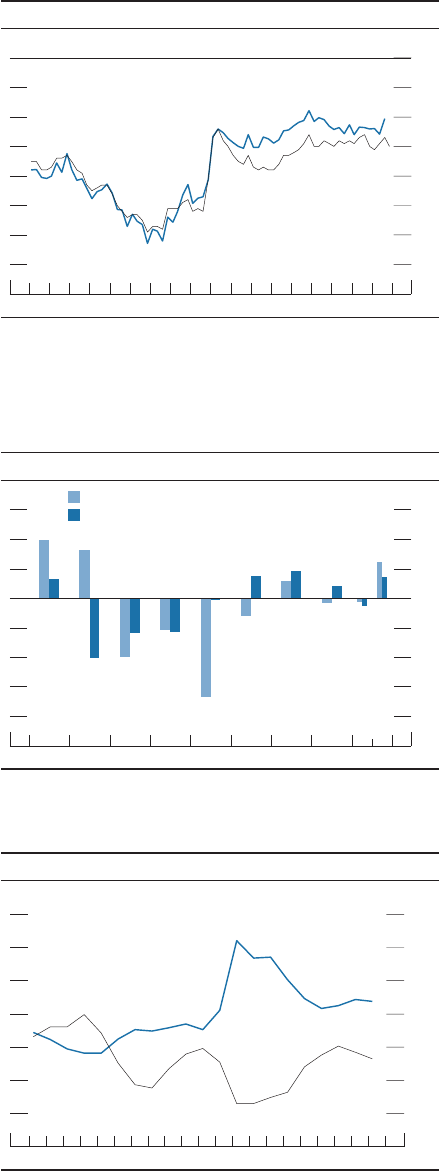

U-5

U-4

U-6

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

Percent

2018201620142012201020082006

2. Measures of labor underutilization

Monthly

Unemployment rate

N

OTE: Unemployment rate measures total unemployed as a percentage of the labor force. U-4 measures total unemployed plus discouraged workers, as a

percentage of the labor force plus discouraged workers. Discouraged workers are a subset of marginally attached workers who are not currently looking for work

because they believe no jobs are available for them. U-5 measures total unemployed plus all marginally attached to the labor force, as a percentage of the labor

force plus persons marginally attached to the labor force. Marginally attached workers are not in the labor force, want and are

available for work, and have looked

for a job in the past 12 months. U-6 measures total unemployed plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a

percentage of the labor force plus all marginally attached workers. The shaded bar indicates a period of business recession as defined by the National Bureau of

Economic Research.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2018 7

has strengthened over the past few years, the

participation rates for prime-age individuals in

each of these groups have risen.

Growth of labor compensation has been

moderate . . .

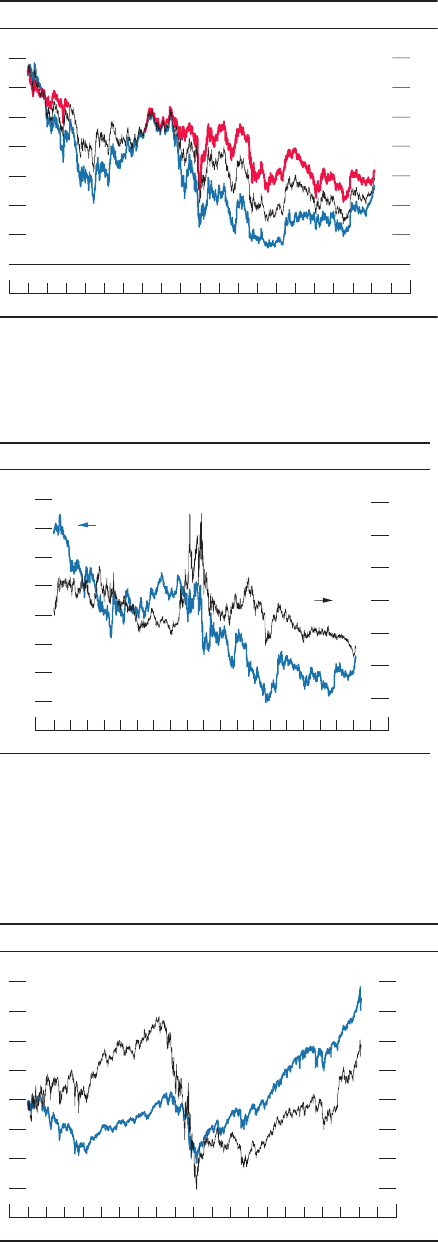

Despite the strong labor market, the available

indicators generally suggest that the growth

of hourly compensation has been moderate.

Growth of compensation per hour in the

business sector—a broad-based measure

of wages, salaries, and benets that is quite

volatile—was 2¼percent over the four

quarters ending in 2017:Q4 (gure5), well

above the low reading in 2016 but about in

line with the average annual increase from

2010 to 2015.

4

The employment cost index—

which also measures both wages and the cost

to employers of providing benets—was up

about 2½percent in the fourth quarter of

2017 relative to its year-ago level, roughly

4. The compensation per hour measure of wages and

salaries declined at the end of 2016, possibly reecting

the shifting of bonuses or other types of income into

2017 in anticipation of a possible cut in personal income

tax rates.

Black or African American

Asian

Hispanic or Latino

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

Percent

2018201620142012201020082006

4. Unemployment rate by race and ethnicity

Monthly

White

N

OTE: Unemployment rate measures total unemployed as a percentage of the labor force. Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of

any race. The shaded bar indicates a period of business recession as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

Employment cost index

Atlanta Fed's Wage Growth Tracker

Average hourly earnings

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Percent change from year earlier

20182016201420122010

5. Measures of change in hourly compensation

Compensation per hour,

business sector

N

OTE: Business-sector compensation is on a four-quarter

percentage

change basis. For the employment cost index, change is over the 12

months

ending in the last month of each quarter; for average hourly earnings,

change

is from 12 months earlier; for the Atlanta Fed's Wage Growth Tracker,

the

data are shown as a 3-month moving average of the 12-month

percent

change.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics; Federal

Reserve

Bank of Atlanta, Wage Growth Tracker.

8 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

The fact that the LFPR for prime-age men remains

below its pre-recession levels might suggest that slack

remains along this dimension; however, the lower

level of the LFPR for prime-age men primarily seems

to reect the continuation of a decades-long secular

decline rather than a cyclical shortfall in their LFPR. In

addition, the U-6 measure of labor utilization—which

includes the unemployed, those marginally attached

to the labor force, and those employed part time who

would like full-time work—rose even more steeply

than the unemployment rate during and immediately

after the recession and has since recovered to near

its pre-recession level. Although there is substantial

uncertainty about the trends in each of the components

of U-6, its current level can be cautiously interpreted

as consistent with a labor market close to full

employment.

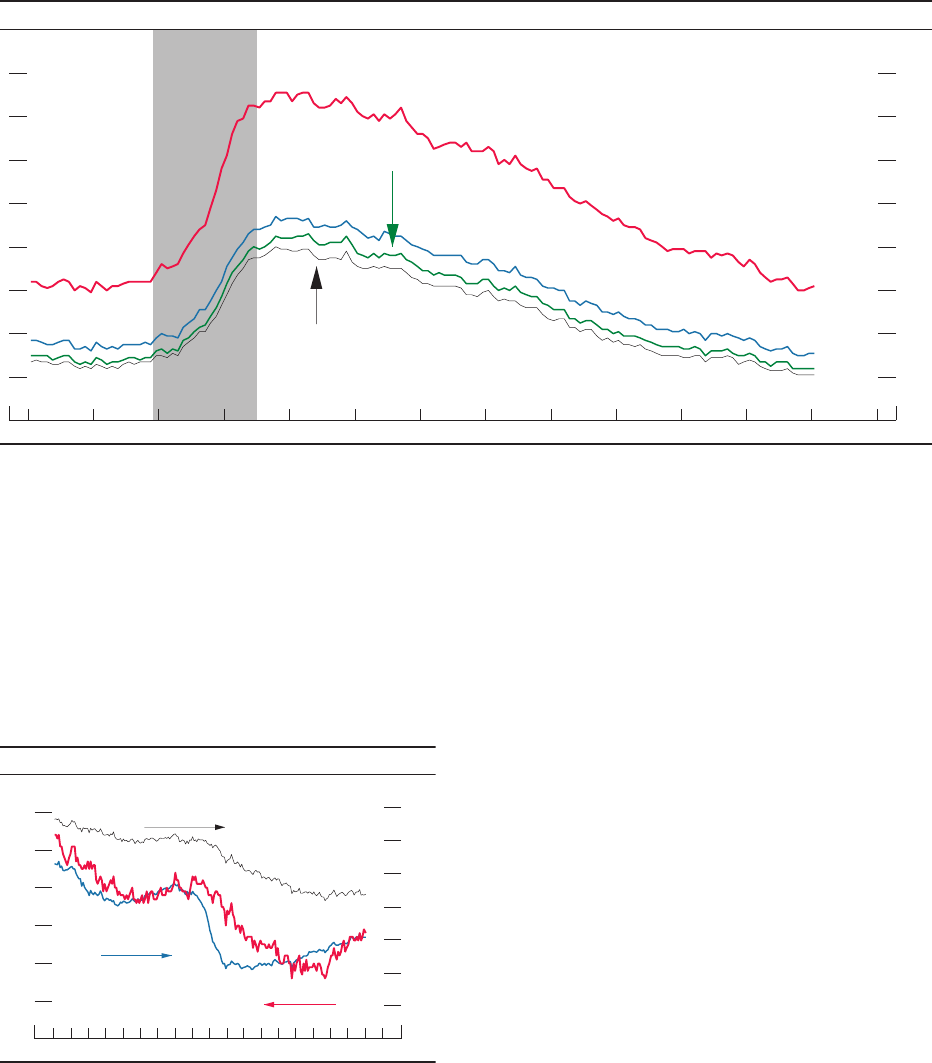

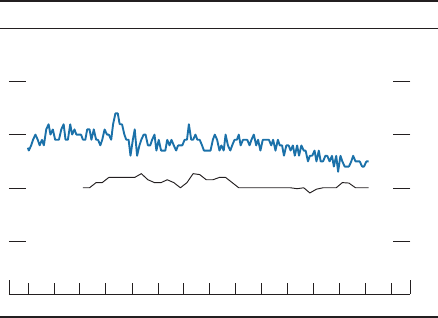

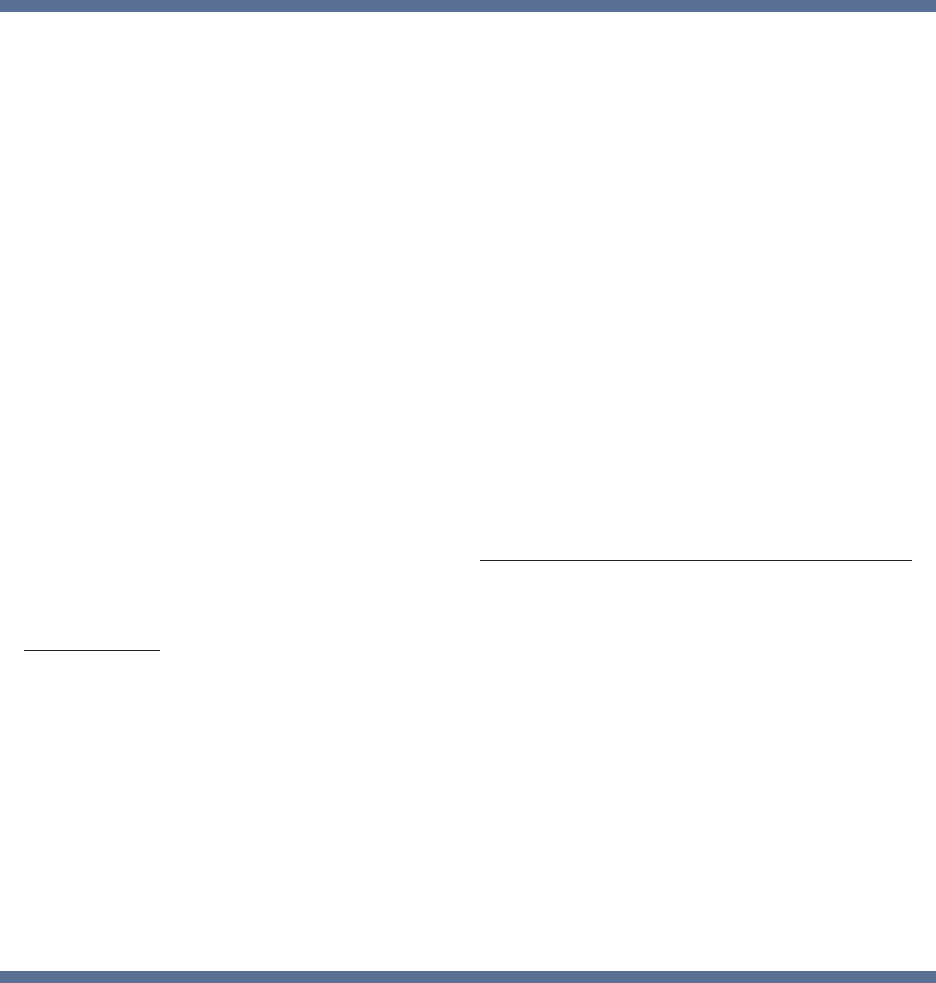

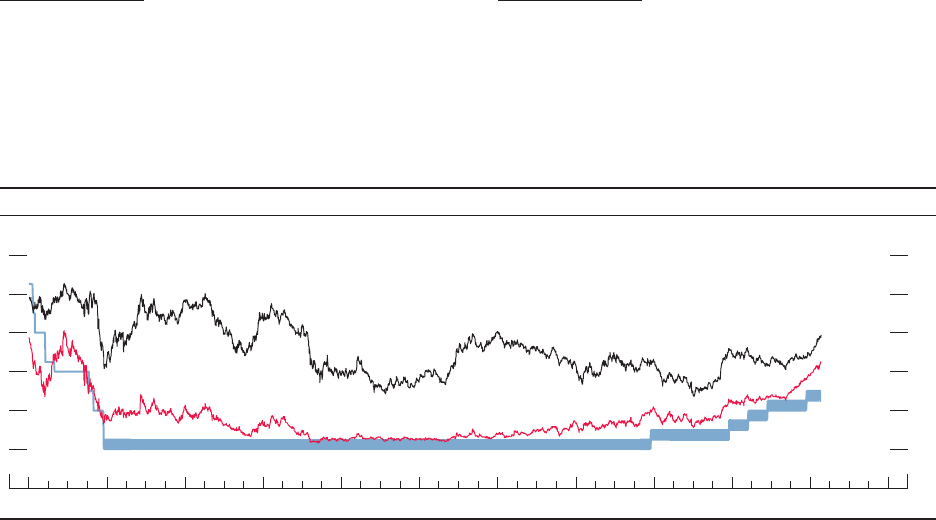

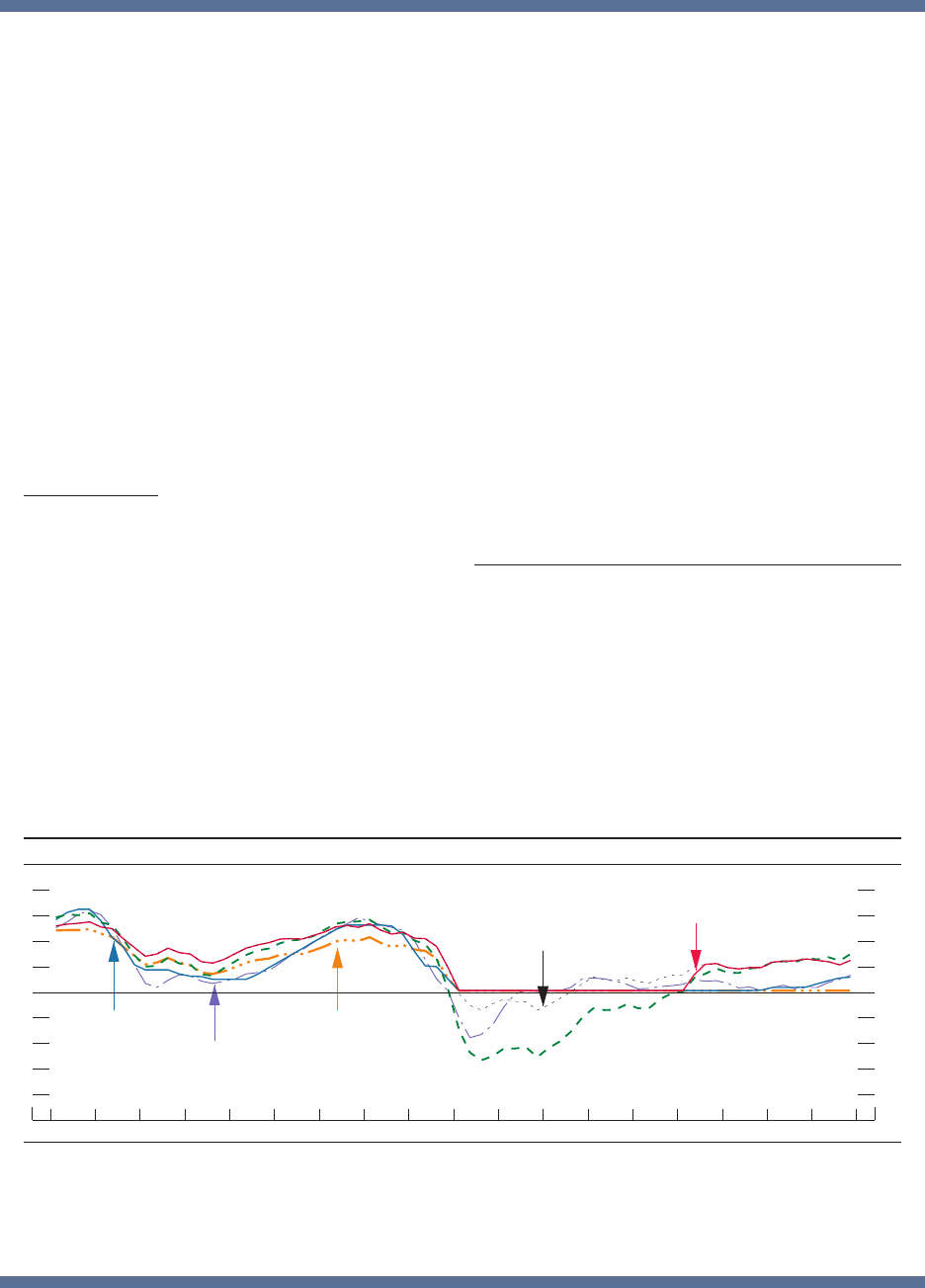

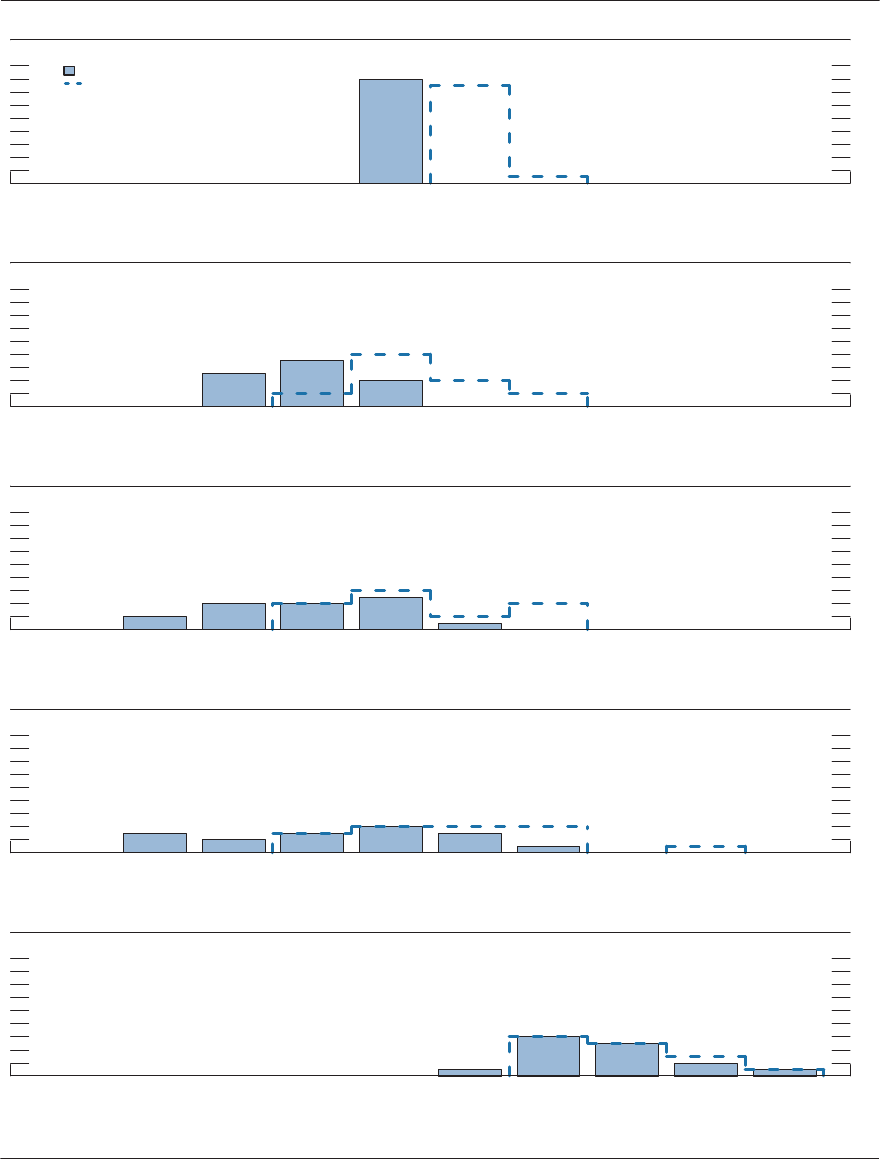

One can also look at less-direct indicators of labor

market tightness. For example, the share of small

businesses with at least one job opening that they view

as hard to ll is now close to its record levels in the late

1990s (as seen in the black line in gure B), consistent

with the notion that as the labor market tightens,

businesses nd it increasingly difcult to hire additional

workers. Similarly, survey measures of households’

Any assessment of labor market tightness is

inherently uncertain, as it involves comparing current

labor market conditions with an estimate of conditions

that would prevail under full employment, where the

latter circumstance cannot be directly observed or

measured and can change over time. Many economists

would describe the labor market as being at full

employment when the unemployment rate has reached

an “equilibrium” level, sometimes called the natural

rate of unemployment or the longer-run normal rate of

unemployment. In judging the level of full employment,

one may also consider additional margins of labor

utilization—including the labor force participation rate

(LFPR), the share of workers employed part time who

would like to be working full time, and individuals

who are classied as marginally attached to the labor

force—as compared with trends in these measures.

While the uncertainty around the “normal” trends in

all of these variables is substantial, the labor market

in early 2018 appears to be near or a little beyond full

employment.

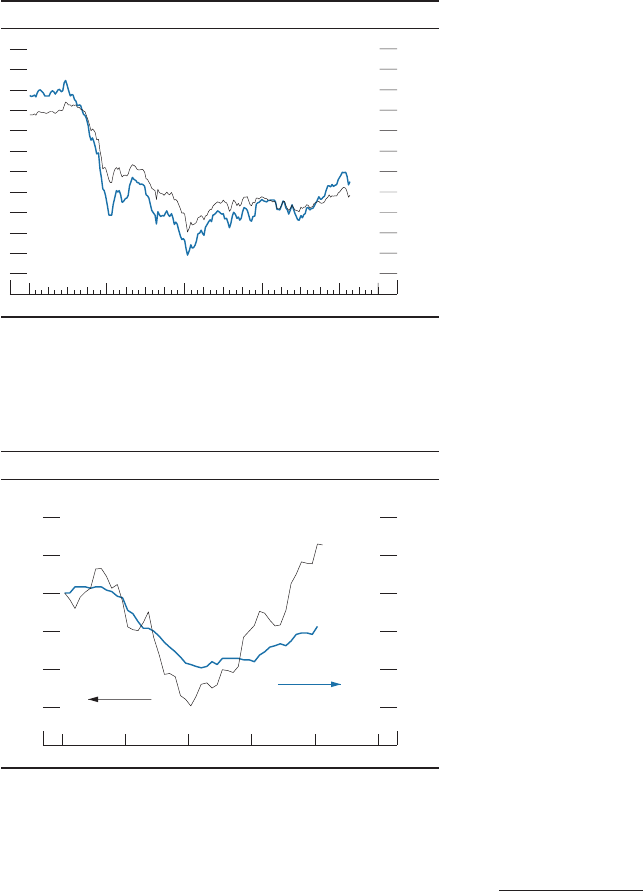

The unemployment rate is now somewhat below

most estimates of its natural rate. Specically, the

unemployment rate in January, at 4.1percent, is

½percentage point below the median of Federal Open

Market Committee (FOMC) participants’ estimates of

the longer-run normal rate of unemployment, which

was reported to have been 4.6percent as of the

December2017 FOMC meeting. The unemployment

rate is also about ½percentage point below the

Congressional Budget Ofce’s (CBO) current estimate

of the natural rate; by this measure, the labor market is

about as tight as it was in the late 1980s but less tight

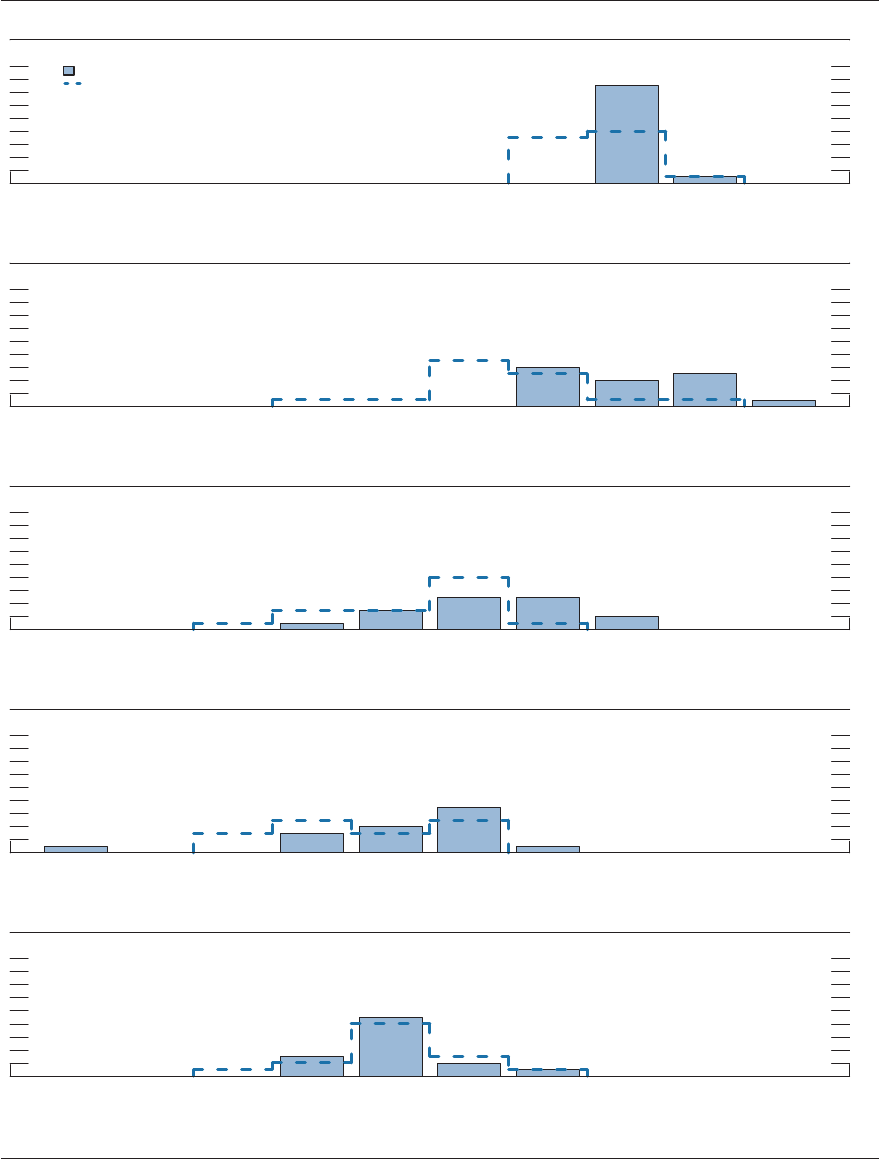

than in the late 1990s (gure A). That said, the median

of FOMC participants’ estimates of the longer-run

normal rate of unemployment and the CBO’s estimate

of the natural rate of unemployment have both been

revised down by about 1percentage point over the past

few years, one indication of the substantial uncertainty

surrounding estimates of the “full employment” rate of

unemployment.

1

As discussed in the main text, the LFPR has been

roughly unchanged, on net, over the past four years,

representing an important cyclical improvement

relative to its declining trend. While estimates of the

trend LFPR are subject to substantial uncertainty and

differ among analysts, the current level of the LFPR

is relatively close to many estimates of its trend.

2

How Tight Is the Labor Market?

1. As another indication of this uncertainty, the range of

FOMC participants’ estimates of the longer-run normal rate of

unemployment was 4.3 to 5.0percent in December2017.

2. For a variety of approaches to assessing the level

of trend LFPR and the associated range of estimates, see

Stephanie Aaronson, Tomaz Cajner, Bruce Fallick, Felix

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

Percent of labor force

2017201320092005200119971993198919851981

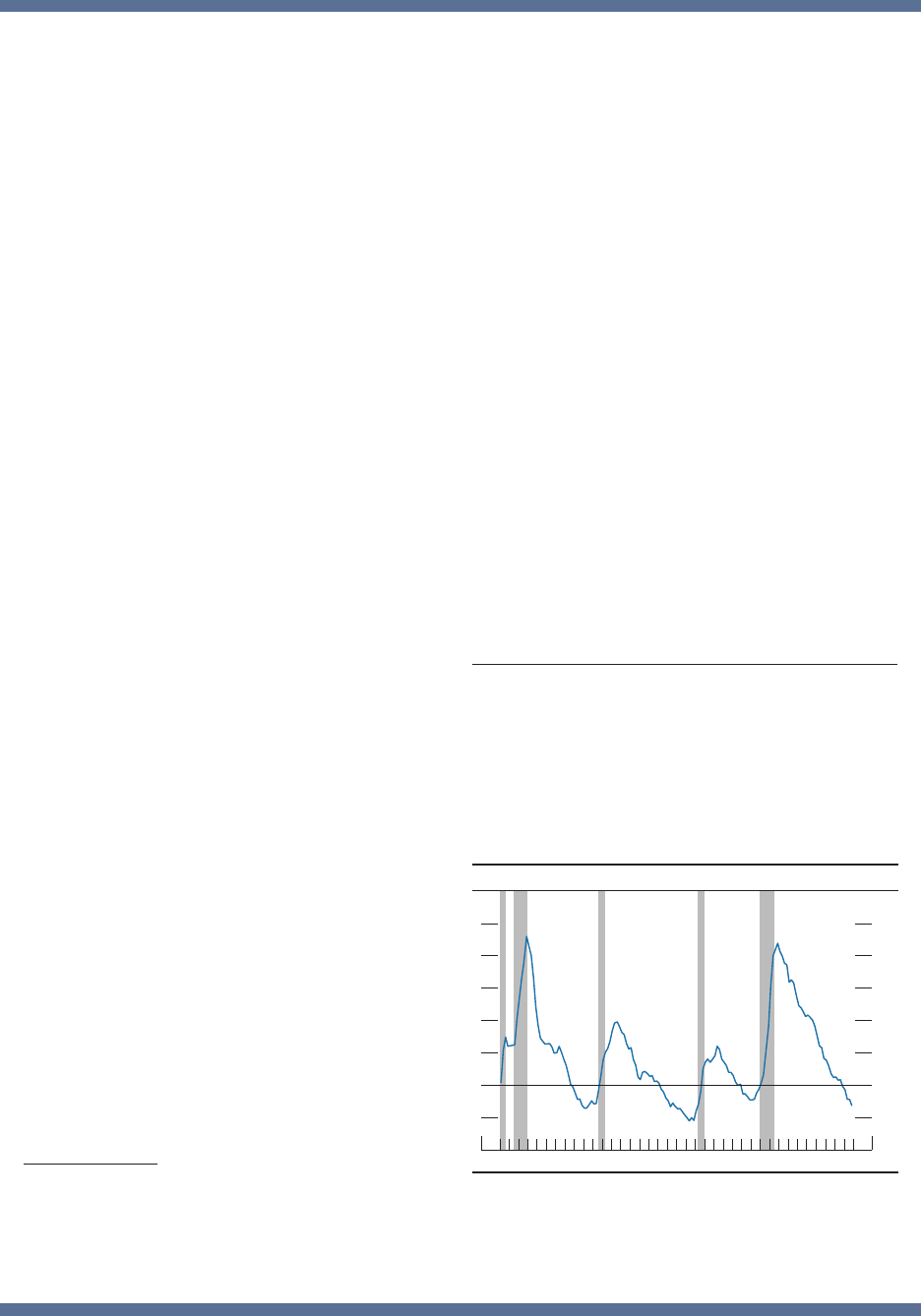

A. Unemployment rate gap

Quarterly

NOTE

: The unemployment rate gap is the unemployment rate minus

the

Congressional

Budget Office's estimate of the natural rate of

unemployment.

The

shaded bars indicate periods of business recession as defined by

the

National Bureau of Economic Research.

SOURCE: For unemployment rate, Bureau of Labor Statistics; for

natural

rate of unemployment, Congressional Budget Office; all via Haver Analytics.

Galbis-Reig,Christopher Smith, and William Wascher (2014),

“Labor Force Participation: Recent Developments and

Future Prospects,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity,

Fall, pp. 197–275, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/

uploads/2016/07/Fall2014BPEA_Aaronson_et_al.pdf.

Estimates of trend LFPR are also provided by the CBO in their

recurring publication The Budget and Economic Outlook and

its updates.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2018 9

taken longer for businesses to nd workers in recent

years, yet wage growth has remained steady or slowed.

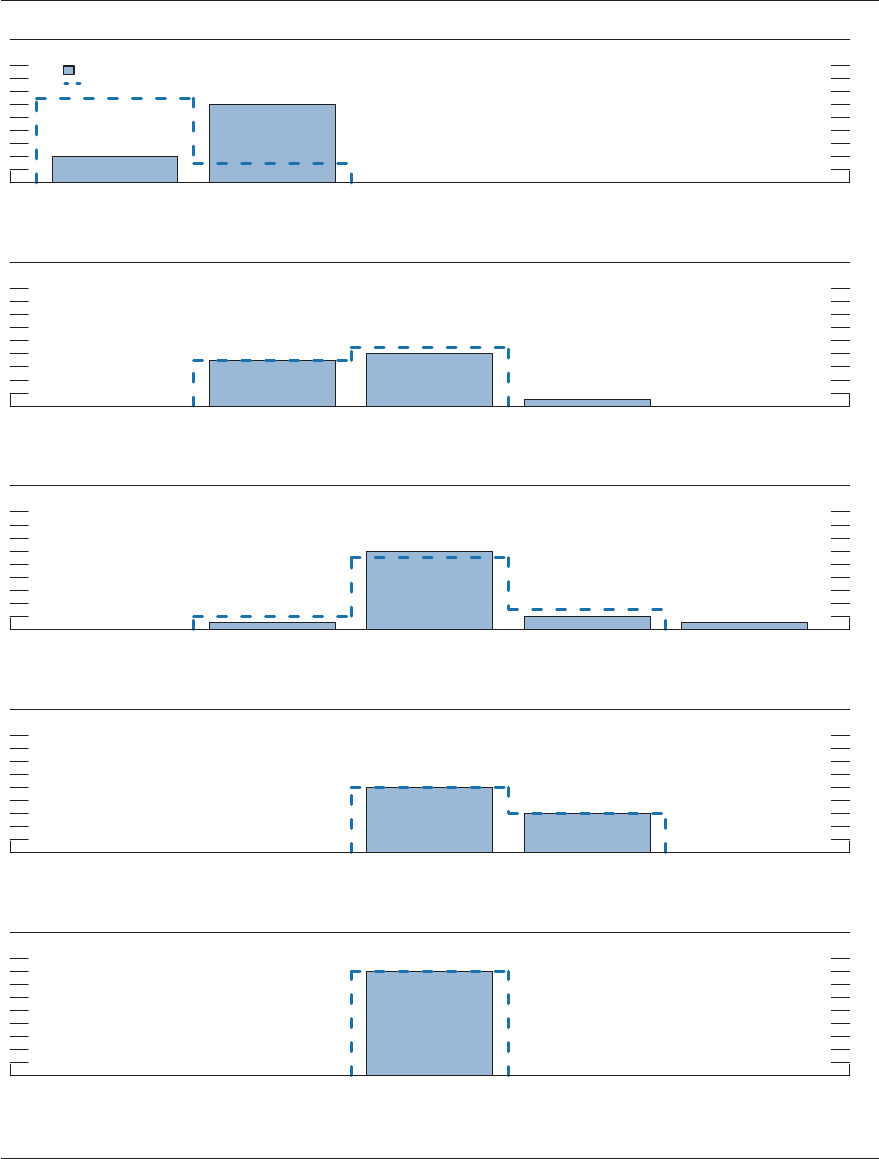

Finally, while the aggregate labor market appears

to be modestly tight at the moment, not all individuals

have beneted equally from these developments. As

discussed in the main text, noticeable differences

in labor market outcomes remain present across

racial and ethnic groups. Moreover, the labor market

improvement in recent years has not been sufcient

to make important progress in narrowing income

inequality. Finally, regional disparities are also striking,

and in certain aspects these disparities have widened

in recent years; for example, the employment-

to-population ratio for prime-age individuals has

recovered less for those outside of metro areas than for

those in metro areas (gure C).

5

perceptions about job availability are currently at high

levels, as shown by the blue line in gure B.

However, despite reports that employers are now

having more difculties nding qualied workers,

hiring has continued apace. Although payroll

employment gains have gradually slowed over time

from about 250,000 per month, on average, in 2014

to about 180,000 per month, on average, in 2017, job

growth remains consistent with further strengthening

in the labor market.

3

Finally, the pace of wage gains

has been moderate; while wage gains have likely been

held down by the sluggish pace of productivity growth

in recent years, serious labor shortages would probably

bring about larger increases than have been observed

thus far.

It is possible that labor shortages have arisen in

certain pockets of the economy, which could be an

early indication of bottlenecks that are not yet readily

apparent in the aggregate labor market. However, even

at the industry level it is difcult to see much evidence of

emerging supply constraints.

4

In some industries, such as

trade and transportation as well as leisure and hospitality,

employment growth has slowed markedly and it has

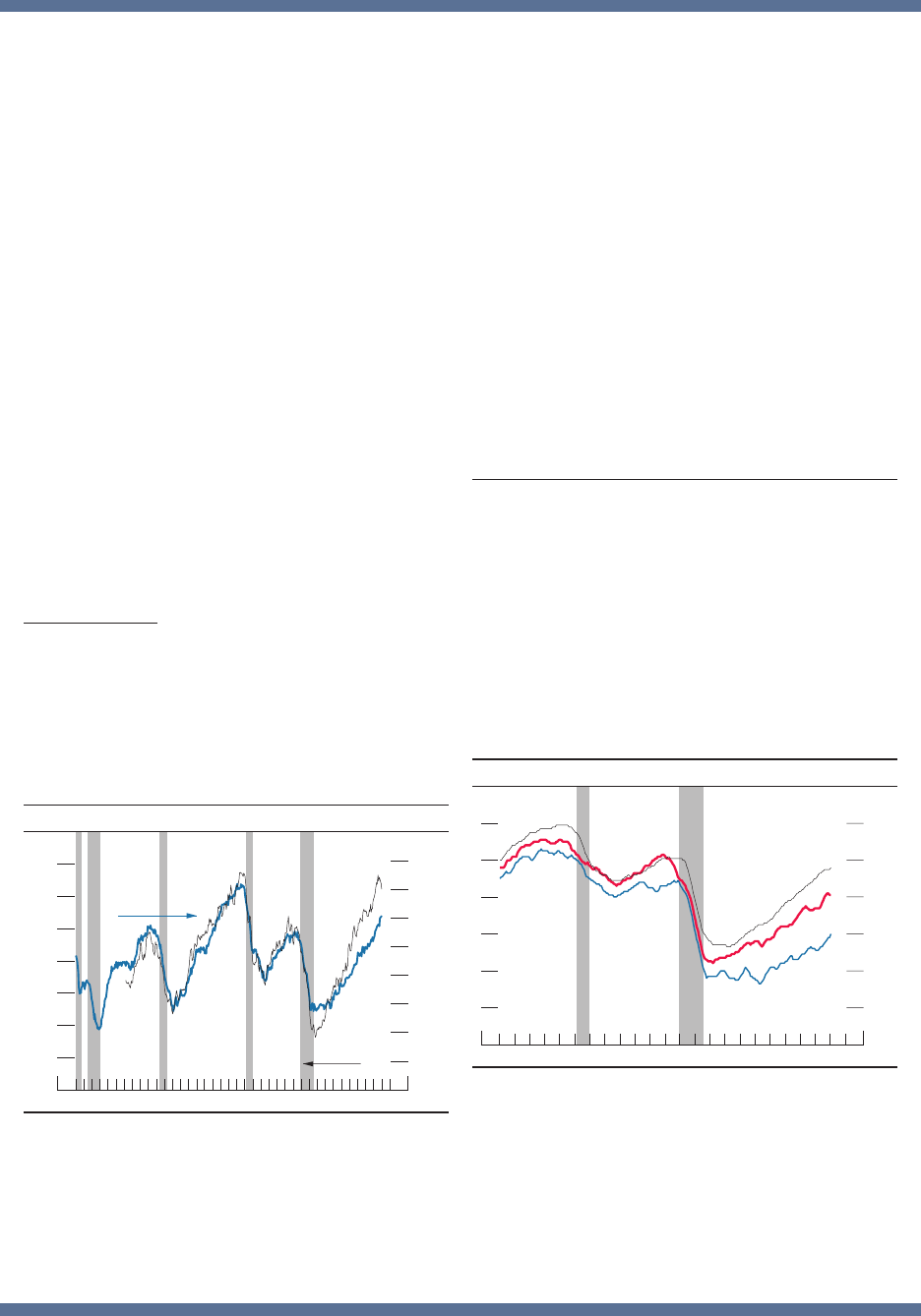

Job availability

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Index

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

2018201420102006200219981994199019861982

B. Job availability and hard-to-fill positions

Percent

Hard-to-fill

N

OTE: Job availability is the proportion of households believing jobs

are

plentiful

minus the proportion believing jobs are hard to get, plus

100.

Hard-to-fill

is the three-month moving average of the percent of

small

businesses

surveyed with at least one hard-to-fill job opening, and it

is

seasonally adjusted by Federal Reserve Board staff. Monthly hard-to-fill data

from

the National Federation of Independent Business start in January

1986.

The

shaded bars indicate periods of business recession as defined by

the

National Bureau of Economic Research. Data are monthly.

SOURCE

: For job availability, Conference Board; for hard-to-fill,

National

Federation of Independent Business.

3. Payroll gains in the range of about 90,000 to 120,000

per month are estimated to be consistent with a constant

unemployment rate and a decline in the labor force

participation rate in line with its demographically driven trend.

4. The analysis behind this statement considered six

broad industries—construction, manufacturing, trade and

Non-metro

Smaller MSAs

72

74

76

78

80

82

Percent

201820162014201220102008200620042002200019981996

C. Prime-age employment-to-population ratio by

metropolitan status

Monthly

Larger MSAs

N

OTE: The data are 12-month centered moving averages.

Larger

metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) consist of 500,000 people or more,

and

smaller MSAs consist of 100,000 to 500,000 people. The shaded bars

indicate

periods of business recession as defined by the National Bureau of Economic

Research.

S

OURCE

: Alison Weingarden (2017), “Labor Market Outcomes

in

Metropolitan and Non-metropolitan Areas: Signs of Growing

Disparities,”

FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve

System, September 25),

www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/

labor-market-outcomes-in-metropolitan-and-non-metropolitan-areas-signs-of

-growing-disparities-20170925.htm. Calculations use data from the

U.S.

Census Bureau, Current Population Survey; note that the Bureau of

Labor

Statistics is involved in the survey process for the Current Population Survey.

transportation, health and education, leisure and hospitality,

and professional and business services.

5. See Alison Weingarden (2017), “Labor Market Outcomes

in Metropolitan and Non-metropolitan Areas: Signs of

Growing Disparities,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of

Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September25),

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/labor-

market-outcomes-in-metropolitan-and-non-metropolitan-

areas-signs-of-growing-disparities-20170925.htm.

10 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

½percentage point faster than its gain a year

earlier. Among measures that do not take

account of benets, average hourly earnings

rose slightly less than 3percent through

January of this year, a gain that was somewhat

faster than the average increase in the

preceding few years. Similarly, the measure

of wage growth computed by the Federal

Reserve Bank of Atlanta that tracks median

12-month wage growth of individuals

reporting to the Current Population Survey

showed an increase of about 3percent in

January, similar to its readings from the past

three years and above the average increase in

the preceding few years.

5

. . . and likely was restrained by slow

growth of labor productivity

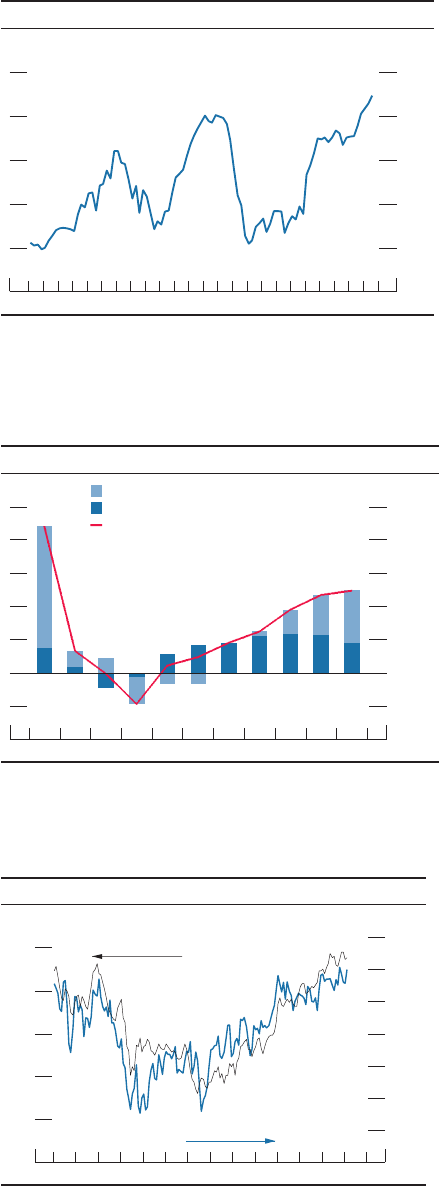

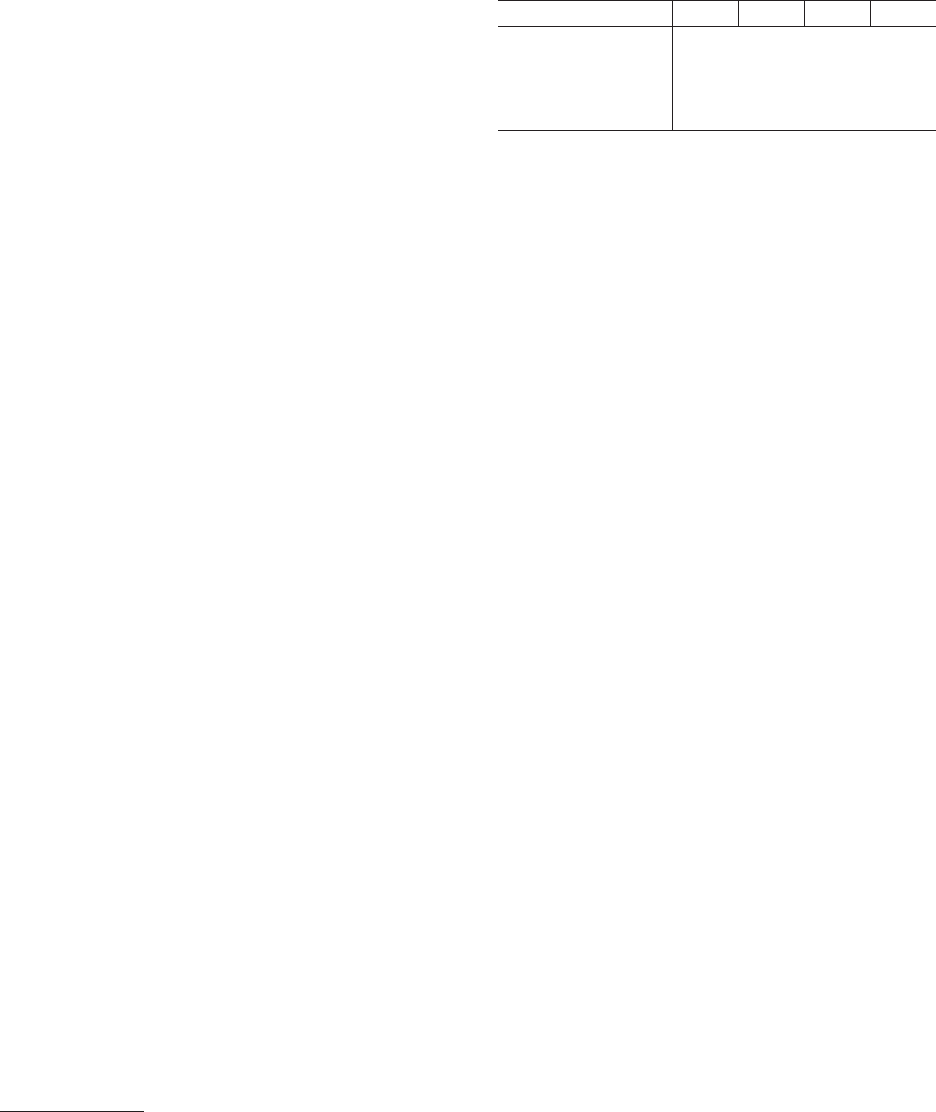

These moderate rates of compensation gain

likely reect the osetting inuences of a

tightening labor market and persistently

weak productivity growth. Since 2008, labor

productivity has increased only a little more

than 1percent per year, on average, well

below the average pace from 1996 through

2007 and also below the gains in the 1974–95

period (gure6). Considerable debate remains

about the reasons for the general slowdown in

productivity growth and whether it will persist.

The slowdown may be partly attributable

to the sharp pullback in capital investment

during the most recent recession and the

relatively long period of modest growth

in investment that followed, but a reduced

pace of capital deepening can explain only

a portion of the step-down. Beyond that,

some economists think that more recent

technological advances, such as information

technology, have been less revolutionary than

earlier general-purpose technologies, such as

electricity and internal combustion. Others

have pointed to a slowdown in the speed at

which capital and labor are reallocated toward

their most productive uses, which is reected

in fewer business start-ups and a reduced

5. The Atlanta Fed’s measure diers from others in

that it measures the wage growth only of workers who

were employed both in the current survey month and

12months earlier.

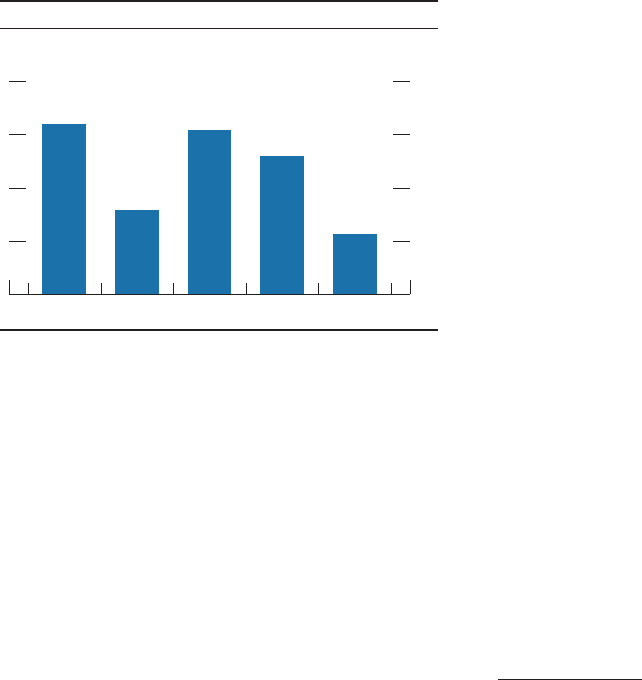

1

2

3

4

Percent, annual rate

6. Change in business-sector output per hour

1948–

73

1974–

95

1996–

2000

2001–

07

2008–

present

NOTE

: Changes are measured from Q4 of the year immediately

preceding

the period through Q4 of the final year of the period. The final period

is

measured from 2007:Q4 through 2017:Q4.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2018 11

pace of hiring and investment by the most

innovative rms. Still others argue that there

have been important innovations in many

elds in recent years, from energy to medicine,

often underpinned by ongoing advances in

information technology, which augurs well for

productivity growth going forward. However,

those economists note that such productivity

gains may appear only slowly as new rms

emerge to exploit the new technologies and

as incumbent rms invest in new vintages of

capital and restructure their businesses.

Price ination remains below 2percent,

but the monthly readings picked up

toward the end of 2017

Consumer price ination, as measured by

the 12-month change in the price index for

personal consumption expenditures (PCE),

remained below the FOMC’s longer-run

objective of 2percent during most of 2017.

The PCE price index increased 1.7percent

over the 12 months ending in December2017,

about the same as in 2016 (gure7). Core

ination, which typically provides a better

indication than the headline measure of

where overall ination will be in the future,

was 1.5percent over the 12months ending in

December2017—0.4percentage point lower

than it had been one year earlier.

Both measures of ination reected some

weak readings in the spring and summer

of 2017. A portion of those weak readings

seemed attributable to idiosyncratic events,

such as a steep 1-month decline in the price

index for wireless telephone services. However,

the monthly readings on core ination were

somewhat higher during the last few months

of 2017, in contrast to the more typical pattern

that has prevailed in recent years in which

readings around the end of the year have

tended to be slightly below average. Moreover,

the 12-month change in the trimmed mean

PCE price index—an alternative indicator of

underlying ination produced by the Federal

Reserve Bank of Dallas that may be less

sensitive to idiosyncratic price movements—

was 1.7percent in December2017 and has

slowed by less than core PCE price ination

Excluding food

and energy

Trimmed mean

+

_

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

12-month percent change

2017201620152014201320122011

7. Change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures

Monthly

Total

NOTE

: The data extend through December 2017; changes are from one year

earlier.

SOURCE: For trimmed mean, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas; for all else,

Bureau of Economic Analysis; all via Haver Analytics.

12 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

over the past 12 months.

6

(For more discussion

of ination both in the United States and

abroad, see the box “Low Ination in the

Advanced Economies.”)

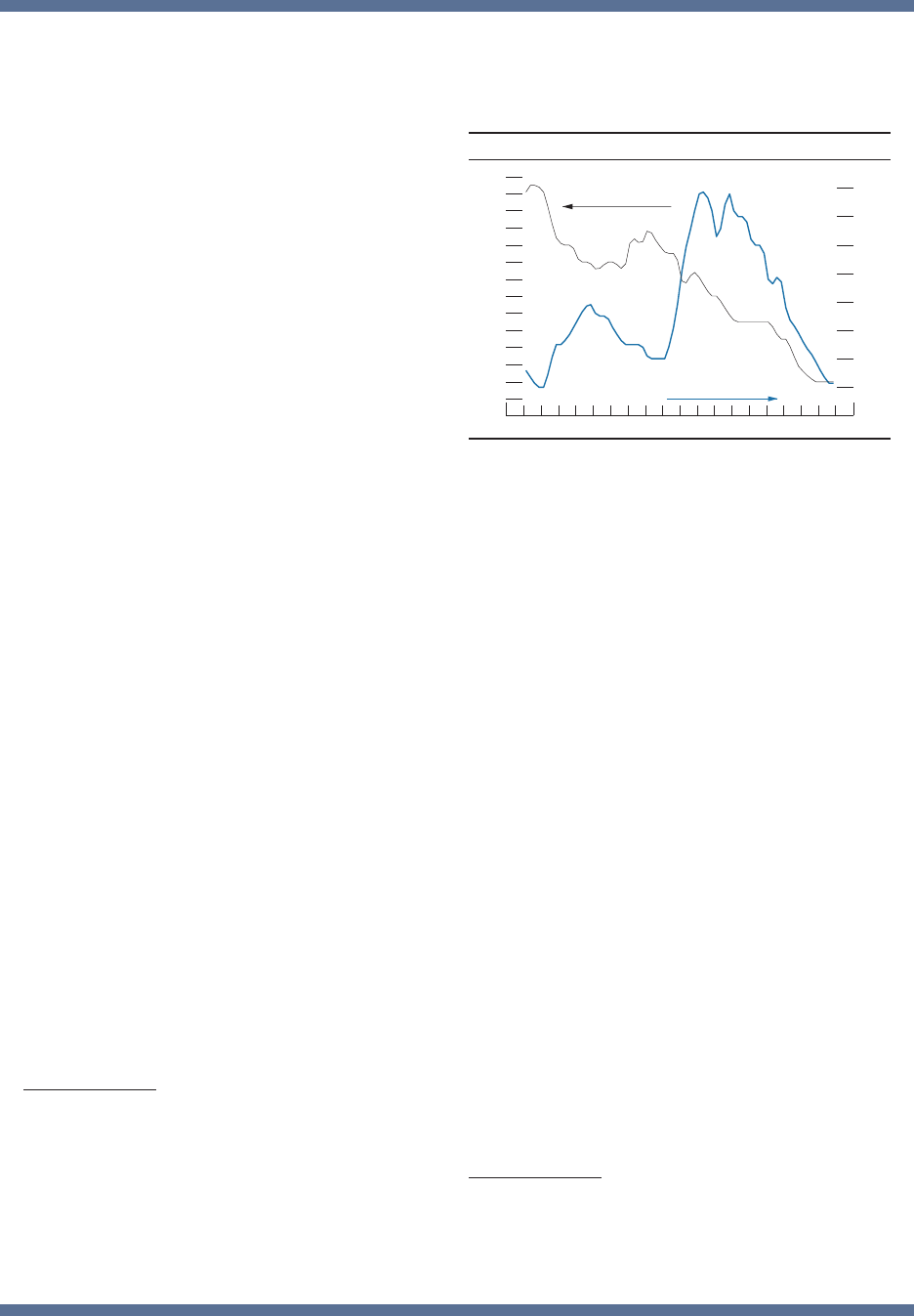

Oil and metals prices increased notably

Headline ination was a little higher than

core ination last year, which reected a rise

in consumer energy prices. The price of crude

oil rose from $48 per barrel at the end of June

to a peak of about $70 per barrel early in the

year and, even after recent declines, remains

more than 30percent above its mid-2017 level

(gure8). The upswing in oil prices appears to

have been driven primarily by strengthening

global demand as well as OPEC’s decision to

further extend its November2016 production

cuts through the end of 2018. The higher oil

prices fed through to moderate increases in the

cost of gasoline and heating oil.

Ination momentum was also supported by

nonfuel import prices, which rose throughout

2017 in part because of dollar depreciation

(gure9). That development marked a turn

from the past several years, during which

nonfuel import prices declined or held at.

In addition to the decline in the dollar,

nonfuel import prices were driven higher by a

substantial increase in the price of industrial

metals. Despite recent volatility, metals prices

remain higher, on net, boosted primarily by

improved prospects for global demand and

also by government policies that restrained

production in China.

In contrast, headline ination has been

held down by consumer food prices, which

increased only about ½percent in 2017 after

having declined in 2016. Food prices have

6. The trimmed mean index excludes whatever prices

showed the largest increases or decreases in a given

month; for example, the sharp decline in prices for

wireless telephone services in March2017 was excluded

from this index.

Spot price

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

Dollars per barrel

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

8. Brent spot and futures prices

Weekly

24-month-ahead

futures contracts

N

OTE

: The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend

through

February 21, 2018.

S

OURCE: ICE Brent Futures via Bloomberg.

Nonfuel import prices

94

96

98

100

102

104

January 2014 = 100

70

80

90

100

110

120

20182017201620152014

9. Nonfuel import prices and industrial metals indexes

January 2014 = 100

Industrial metals

N

OTE

: The data for nonfuel import prices are monthly. The data for

industrial

metals are a monthly average of daily data and extend through

February 21, 2018.

S

OURCE

: For nonfuel import prices, Bureau of Labor Statistics; for

industrial

metals, S&P GSCI Industrial Metals Spot Index via Haver

Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2018 13

been restrained by softness in the prices of

farm commodities, which in turn has reected

robust supply in the United States and abroad.

Although the harvests for many crops in the

United States declined in 2017, they were

larger than had been expected earlier in

the year.

Survey-based measures of ination

expectations have been generally stable. . .

Expectations of ination likely inuence actual

ination by aecting wage- and price-setting

decisions. Survey-based measures of ination

expectations at medium- and longer-term

horizons have remained generally stable. In the

Survey of Professional Forecasters conducted

by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia,

the median expectation for the annual rate of

increase in the PCE price index over the next

10years has been around 2percent for the past

several years (gure10). In the University of

Michigan Surveys of Consumers, the median

value for ination expectations over the next

5 to 10years—which had drifted downward

starting in 2014—has held about at since the

end of 2016 at a level that is a few tenths lower

than had prevailed through 2014.

. . . and market-based measures of

ination compensation have increased in

recent months but remain relatively low

Ination expectations can also be gauged

by market-based measures of ination

compensation, though the inference is not

straightforward because market-based

measures can be importantly aected

by changes in premiums that provide

compensation for bearing ination and

liquidity risks. Measures of longer-term

ination compensation—derived either from

dierences between yields on nominal Treasury

securities and those on comparable Treasury

Ination-Protected Securities (TIPS) or from

ination swaps—have increased since June,

returning to levels seen in early 2017, but

Michigan survey expectations

for next 5 to 10 years

1

2

3

4

Percent

2018201620142012201020082006

SPF expectations

for next 10 years

10. Median inflation expectations

NOTE

: The Michigan survey data are monthly and extend

through

February; the February data are preliminary. The SPF data for

inflation

expectations for personal consumption expenditures are quarterly and

extend

from 2007:Q1 through 2018:Q1.

SOURCE: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers; Federal

Reserve

Bank of Philadelphia, Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF).

14 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

But our understanding of the forces that drive

ination is imperfect, and the fact that many advanced

economies are experiencing low ination at the same

time suggests that other, possibly more persistent,

factors may be at work. As one possibility, the natural

rate of unemployment—the rate at which labor markets

exert neither upward nor downward pressure on

ination—is highly uncertain, and it could be lower

in many economies than most economists estimate.

Alternatively, ination expectations could be lower

than suggested by the available indicators.

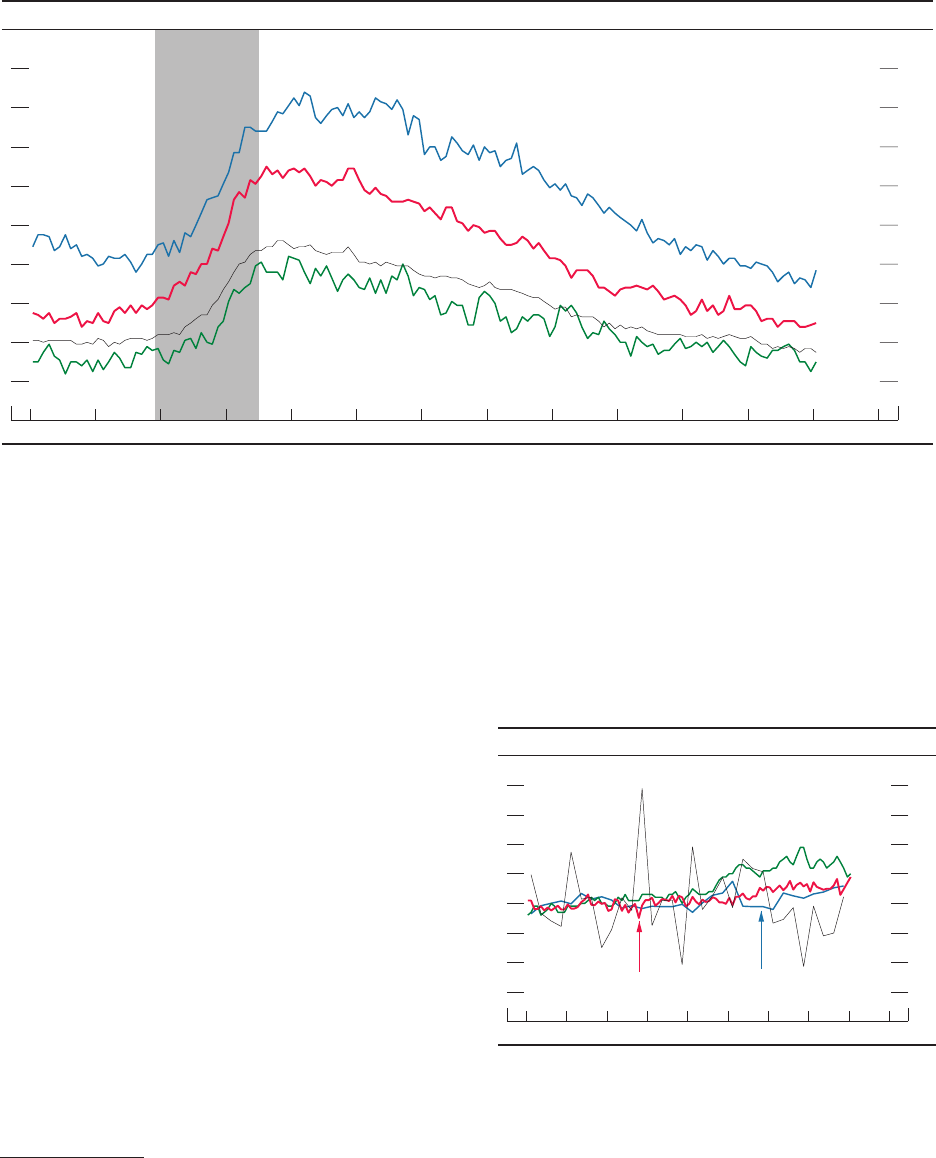

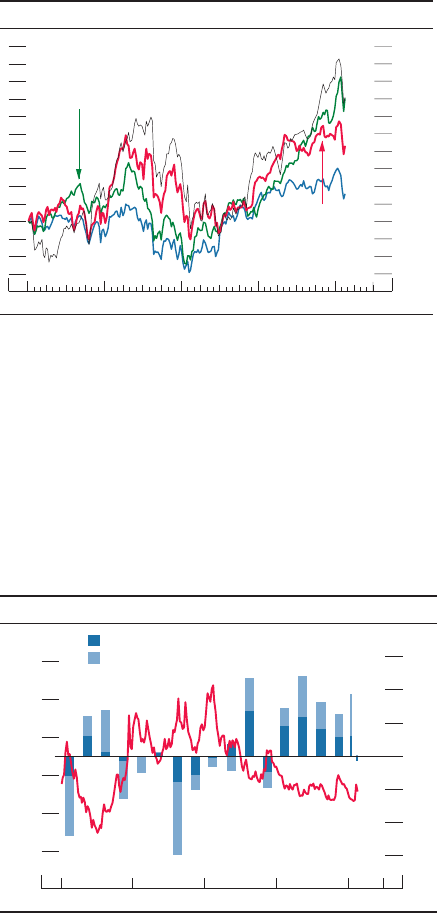

More-fundamental changes in the global economy

could also be contributing to the recent stretch of

lower ination. First, anecdotal reports suggest that

technological changes could be reducing pricing

power in many industries, holding down ination as

that occurs.

2

For example, the increased prevalence of

Internet shopping allows consumers to compare prices

more easily across sellers, possibly implying greater

competition that could be putting downward pressure

on consumer prices (gure C). While this hypothesis is

certainly plausible, it does not easily square with the

observation that, at least within the United States, prot

margins have been high (gure D).

3

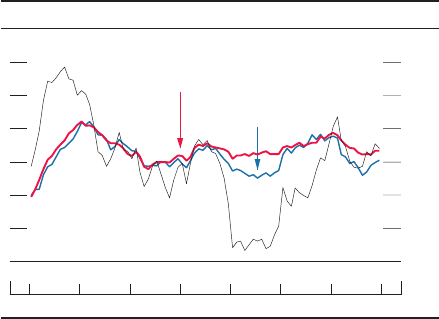

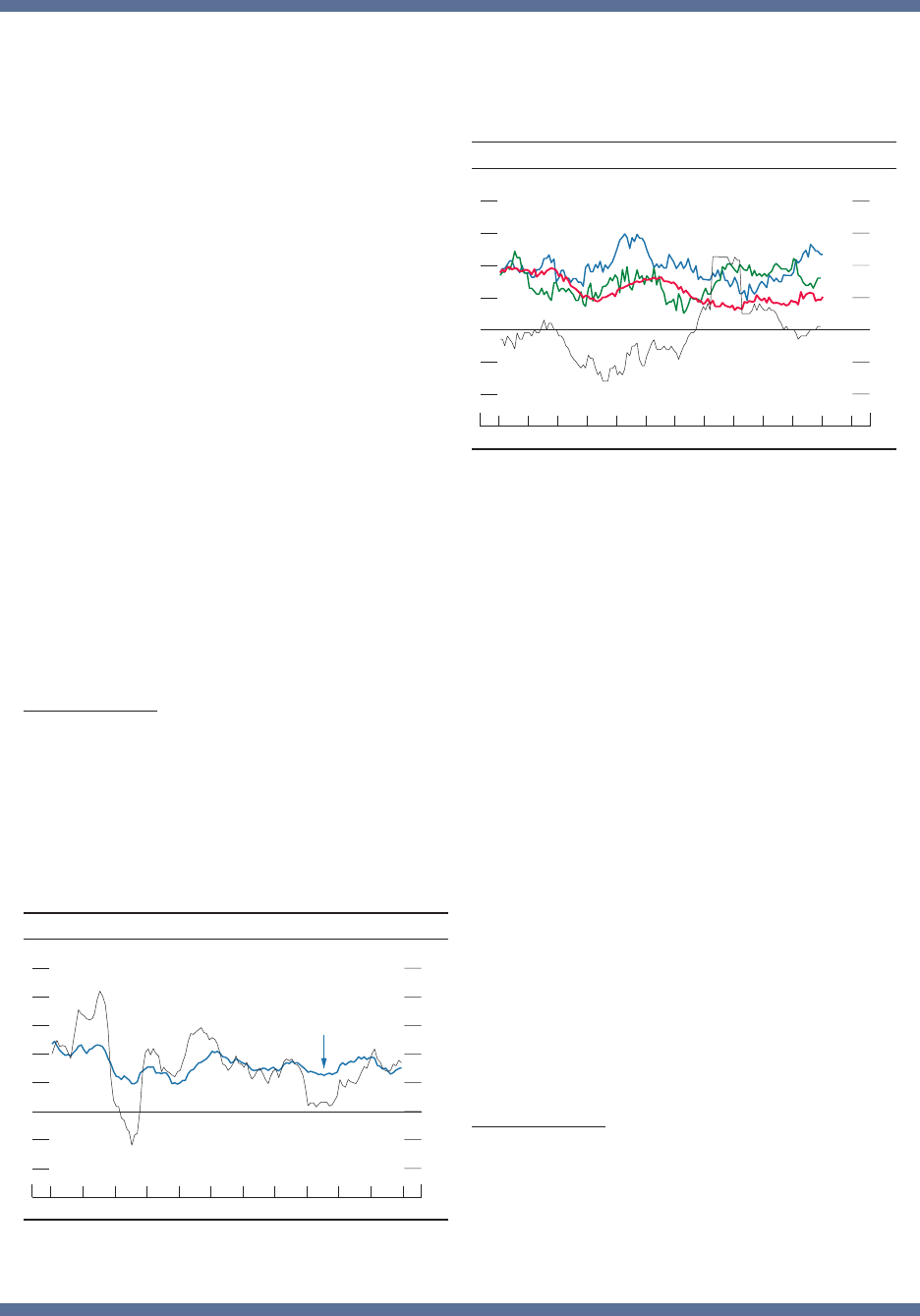

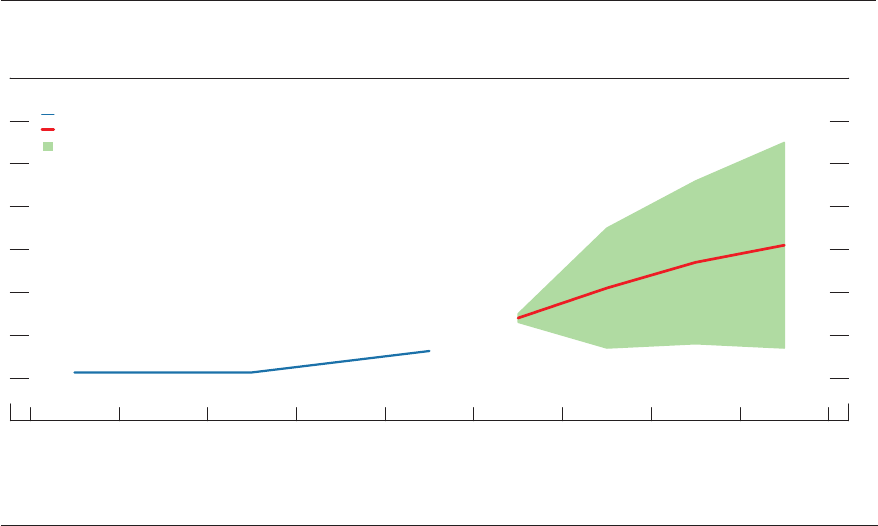

Ination has been persistently low in recent years

across many advanced economies. In the United States,

both overall ination and core (excluding food and

energy prices) ination, as measured by the price index

for personal consumption expenditures, have run below

2percent for most of the period since 2008 (gureA).

In other advanced economies, measures of core

ination have run even lower in some cases, with core

ination in the euro area currently at around 1percent

and in Japan at close to zero (gure B).

What explains this period of low ination? Across

the advanced economies, the main factors holding

ination down likely include the extended period of

economic slack following the Great Recession and

the falling prices of oil and other commodities from

around mid-2014 to early 2016. In the United States,

ination also has been held down by the rise in the

foreign exchange value of the dollar from mid-2014

through 2016. The low core U.S. ination in 2017 has

been more of a puzzle (albeit modest in magnitude)

and harder to associate with an identiable cause.

1

As is discussed in the December2017 Summary of

Economic Projections (Part 3 of this report), most

Federal Reserve policymakers view these recent low

ination readings as likely to prove transitory and

project U.S. ination this year to move closer to their

2percent objective. Many private forecasters appear to

share this view.

Low Ination in the Advanced Economies

Excluding food

and energy

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

12-month percent change

201720152013201120092007

A. Change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures

Monthly

Total

NOTE

: The data extend through December 2017; changes are from one year

earlier.

S

OURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

1. For additional discussion of the reasons for low ination

in the United States, see Janet Yellen (2017), “Ination,

Uncertainty, and Monetary Policy,” speech delivered at

“Prospects for Growth: Reassessing the Fundamentals,” 59th

Annual Meeting of the National Association for Business

Economics, Cleveland, Ohio, September26, https://www.

federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20170926a.htm.

United Kingdom

Canada

Euro area

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

12-month percent change

201820162014201220102008

B. Inflation excluding food and energy in selected

advanced foreign economies

Monthly

Japan

N

OTE:

The data for the euro area incorporate the flash estimate for January

2018. The data for Canada and Japan extend through December 2017.

SOURCE:

For the United Kingdom, Office for National Statistics; for Japan,

Ministry

of International Affairs and Communications; for the euro

area,

Statistical

Office of the European Communities; for Canada,

Statistics

Canada; all via Haver Analytics.

2. Goldman Sachs (2017), “The Amazon Effect in

Perspective,” U.S. Economics Analyst (New York: Goldman

Sachs, September30).

3. See Council of Economic Advisers (2016), “Benets

of Competition and Indicators of Market Power,” Council

of Economic Advisers Issue Brief (Washington: CEA, April),

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/les/page/

les/20160414_cea_competition_issue_brief.pdf.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2018 15

than other consumers.

6

Others have pointed to a

slowdown in medical services price increases across

countries, possibly associated with either health-care

reform or scal austerity.

7

This slowdown has had a

material effect on U.S. ination, though the extent to

which these declines will persist is uncertain.

In summary, while standard economic models

appear to explain much of the post–Great Recession

period of low ination, they do not preclude other

explanations. Even as most policymakers expect

ination in their economies to move back to their

targets over time, they remain attentive to the possibility

that factors not included in those models, such as those

described here, may keep ination low. At the same

time, they are attentive to the opposite risk of ination

moving undesirably high, should tightening demand

conditions lead to faster rises in wages and prices than

currently anticipated.

Second, some observers have pointed to global

developments as helping to explain persistent low

ination across countries. These developments

include economic slack abroad or the integration of

emerging economies into the world economy, leading

to increased competition or downward pressures on

wages.

4

But the evidence that global slack can help

explain ination in a given country, beyond its effect

on commodity and import prices, is mixed at best.

5

Moreover, measures of integration, such as global

trade as a fraction of gross domestic product or the

participation in global value chains, appear to have

leveled off in recent years.

A number of other explanations for low global

ination have been advanced as well. These

explanations include some tentative evidence

suggesting that the aging of the population could be

exerting downward pressure on trend ination, perhaps

because retirees may tend to be more price conscious

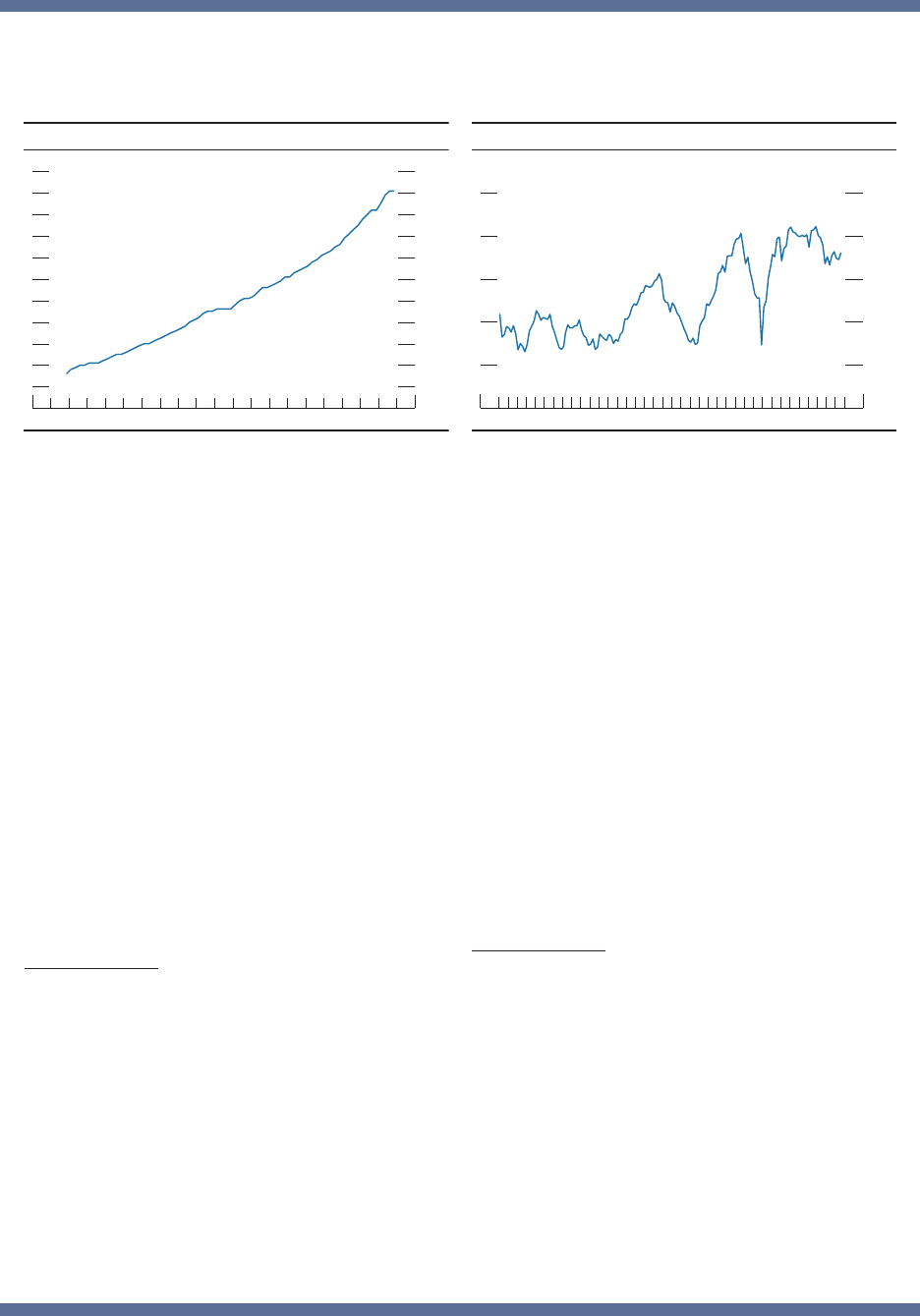

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Percent

2017201420112008200520021999

C. E-commerce sales as a share of retail sales

Quarterly

NOTE: E-commerce sales are sales of goods and services where an order

is

placed

by the buyer or where the price and terms of sale are negotiated

over

an online system. Payment may or may not be made online.

S

OURCE: Retail Indicators Branch, U.S. Census Bureau.

6

8

10

12

14

Percent

20172012200720021997199219871982

Quarterly

D. Corporate profits as a share of gross national product

NOTE: The data extend through 2017:Q3. Corporate profits

include

inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments.

S

OURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

4. See Claudio Borio and Andrew Filardo (2007),

“Globalisation and Ination: New Cross-Country Evidence

on the Global Determinants of Domestic Ination,” BIS

Working Papers 227 (Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International

Settlements, May), www.bis.org/publ/work227.pdf; and

Raphael Auer, Claudio Borio, and Andrew Filardo (2017), “The

Globalisation of Ination: The Growing Importance of Global

Value Chains,” BIS Working Papers 602 (Basel, Switzerland:

Bank for International Settlements, January), www.bis.org/

publ/work602.pdf.

5. See Jane Ihrig, Steven B. Kamin, Deborah Lindner,

and Jaime Marquez (2010), “Some Simple Tests of the

Globalization and Ination Hypothesis,” International Finance,

vol. 13 (Winter), pp. 343–75; and European Central Bank

(2017), “Domestic and Global Drivers of Ination in the Euro

Area,” ECB Economic Bulletin, no. 4 (June), pp. 72–96, https://

www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ebart201704_01.en.pdf.

6. See Jong-Won Yoon, Jinill Kim, and Jungjin Lee (2014),

“Impact of Demographic Changes on Ination and the

Macroeconomy,” IMF Working Paper WP/14/210 (Washington:

International Monetary Fund, November), https://www.imf.

org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2014/wp14210.pdf. However, other

evidence suggests increased inationary pressure from an

aging population; see Mikael Juselius and Előd Takáts (2015),

“Can Demography Affect Ination and Monetary Policy?” BIS

Working Papers 485 (Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International

Settlements, February), https://www.bis.org/publ/work485.pdf.

7. See Tim Mahedy and Adam Shapiro (2017), “What’s

Down with Ination?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2017-35 (San

Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, November),

https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/

economic-letter/2017/november/contribution-to-low-pce-

ination-from-healthcare); and Goldman Sachs (2017), “What

Can We Learn from Lower Ination Abroad?” U.S. Economics

Analyst (New York: Goldman Sachs, November12)

16 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

nevertheless remain relatively low (gure11).

7

The TIPS-based measure of 5-to-10-year-

forward ination compensation and the

analogous measure of ination swaps are now

slightly lower than 2¼percent and 2½percent,

respectively, with both measures below the

ranges that persisted for most of the 10years

before the start of the notable declines

in mid-2014.

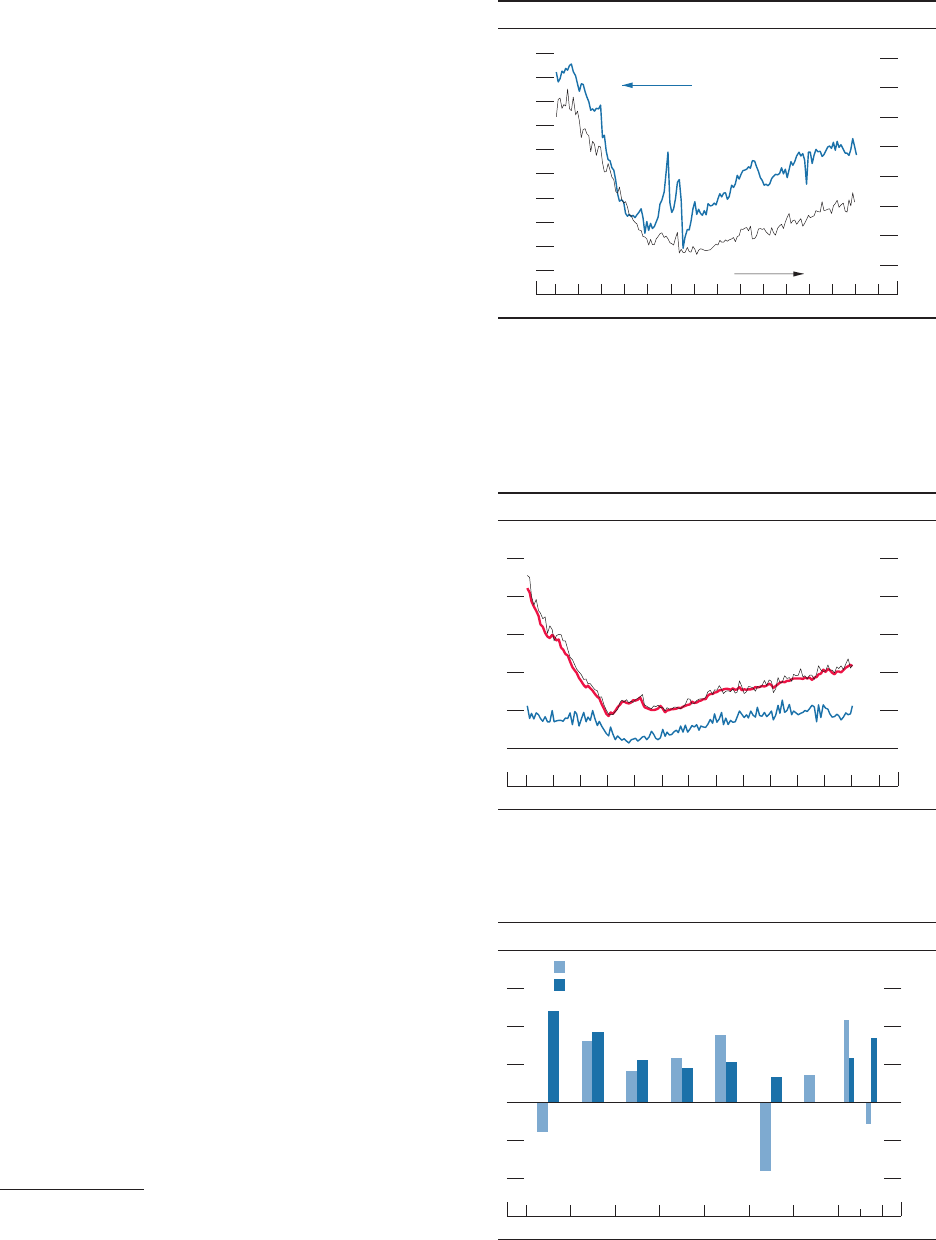

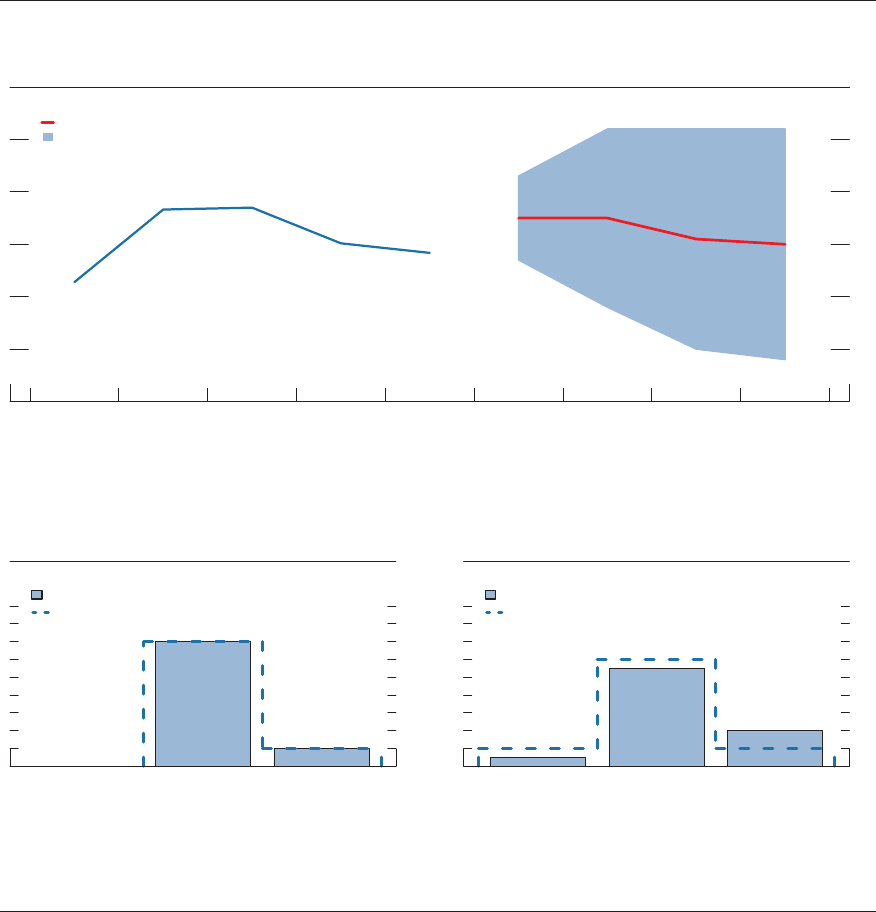

Real gross domestic product growth

picked up in the second half of 2017

Real gross domestic product (GDP) is

reported to have risen at an annual rate of

nearly 3percent in the second half of 2017

after increasing slightly more than 2percent

in the rst half of 2017 (gure12). Much of

that faster growth reects the stabilization

of inventory investment, which had slowed

considerably in the rst half of last year.

Private domestic nal purchases—that is,

nal purchases by U.S. households and

businesses, which tend to provide a better

indication of future GDP growth than most

other components of overall spending—rose

at a solid annual rate of about 3½percent in

the second half of the year, similar to the rst-

half pace.

The economic expansion continues to

be supported by steady job gains, rising

household wealth, favorable consumer

sentiment, strong economic growth abroad,

and accommodative nancial conditions,

including the still low cost of borrowing and

easy access to credit for many households and

businesses. In addition to these factors, very

7. Ination compensation implied by the TIPS

breakeven ination rate is based on the dierence, at

comparable maturities, between yields on nominal

Treasury securities and yields on TIPS, which are indexed

to the headline consumer price index (CPI). Ination

swaps are contracts in which one party makes payments

of certain xed nominal amounts in exchange for cash

ows that are indexed to cumulative CPI ination over

some horizon. Focusing on ination compensation 5 to

10years ahead is useful, particularly for monetary policy,

because such forward measures encompass market

participants’ views about where ination will settle in the

long term after developments inuencing ination in the

short term have run their course.

1

2

3

4

5

Percent, annual rate

2017201620152014201320122011

12. Change in real gross domestic product and gross

domestic income

H1

H2*

*Gross domestic income is not yet available for 2017:H2.

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Gross domestic product

Gross domestic income

Inflation swaps

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Percent

20182016201420122010

11. 5-to-10-year-forward inflation compensation

Weekly

TIPS breakeven rates

N

OTE

:The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend

through

February 16, 2018. TIPS is Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities.

SOURCE: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Barclays; Federal

Reserve

Board staff estimates.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2018 17

upbeat business sentiment appears to have

supported solid growth over the past year.

Ongoing improvement in the labor

market and gains in wealth continue to

support consumer spending . . .

Supported by ongoing improvement in the

labor market, real consumer spending rose at

a solid annual rate of 3percent in the second

half of 2017, a somewhat faster pace than

in the rst half. Real disposable personal

income—that is, income after taxes and

adjusted for price changes—increased at a

modest average rate of 1percent in 2016 and

2017, as real wages changed little over this

period (gure13). With spending growth

estimated to have outpaced income growth, the

personal saving rate has declined considerably

since the end of 2015 (gure14).

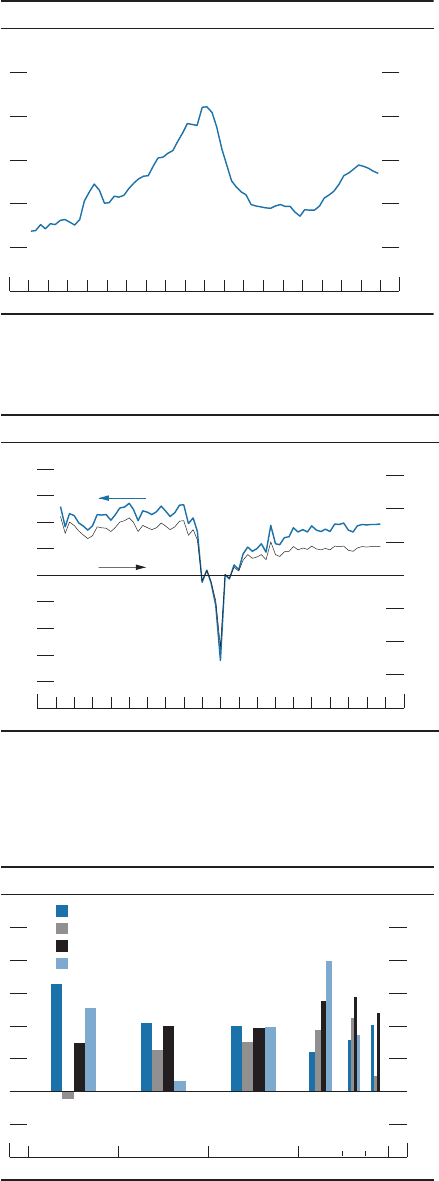

Consumer spending has also been supported

by further increases in household net wealth.

Broad measures of U.S. equity prices rose

robustly last year, though markets have been

volatile in recent weeks; house prices have also

continued to climb, strengthening the wealth

of homeowners (gure15). As a result of the

increases in home and equity prices, aggregate

household net worth rose appreciably in 2017.

In fact, at the end of the third quarter of 2017,

household net worth was 6.7 times the value of

disposable income, the highest-ever reading for

that ratio, which dates back to 1947 (gure16).

. . . borrowing conditions for consumers

remain generally favorable . . .

Consumer credit expanded in 2017 at about

the same pace as in 2016 (gure17). Financing

conditions for most types of consumer loans

are generally favorable. However, banks have

continued to tighten standards on credit card

and auto loans for borrowers with low credit

scores, possibly in response to some upward

drift in delinquency rates for those borrowers.

Mortgage credit has remained readily available

for households with solid credit proles, but

it was still dicult to access for households

with low credit scores or harder-to-document

incomes.

3

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Percent, annual rate

2017201620152014201320122011

13. Change in real personal consumption expenditures

and disposable personal income

H1

H2

SOURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Personal consumption expenditures

Disposable personal income

2

4

6

8

10

12

PercentMonthly

201720152013201120092007

14. Personal saving rate

NOTE: Data are through December 2017.

SOURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

CoreLogic

price index

S&P/Case-Shiller

national index

20

15

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

15

Percent change from year earlier

201720152013201120092007

15. Prices of existing single-family houses

Monthly

Zillow index

N

OTE

: The data for the S&P/Case-Shiller index extend through November

2017.

The data for the Zillow index and the CoreLogic index extend through

December 2017.

SOURCE

: CoreLogic Home Price Index; Zillow; S&P/Case-Shiller U.S.

National Home Price Index. The S&P/Case-Shiller Index is a product of S&P

Dow

Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates. (For Dow Jones Indices

licensing information, see the note on the Contents page.)

18 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Although household borrowing continued to

increase last year, the household debt service

burden—the ratio of required principal and

interest payments on outstanding household

debt to disposable income, measured for the

household sector as a whole—remained low by

historical standards.

. . . and consumer condence is strong

Consumers have remained optimistic about

their economic situation. As measured by the

Michigan survey, consumer sentiment was

solid throughout 2017, likely reecting rising

income, job gains, and low ination (gure18).

Furthermore, the share of households

expecting real income to rise over the next year

or two has continued to strengthen and now

exceeds its pre-recession level.

Activity in the housing sector has

improved modestly

Real residential investment spending increased

around 2percent in 2017, about the same

modest gain that was seen in 2016. Housing

activity was soft in the spring and summer,

possibly reecting the rise in mortgage interest

rates early in the year, and then picked up

toward the end of the year. For the year as a

whole, sales of new and existing homes gained,

and single-family housing starts increased

(gures 19 and 20). In contrast, multifamily

housing starts continued to edge down from

the solid pace seen in 2016. Going forward,

lean inventories are likely to support further

gains in homebuilding activity, as the months’

supply of homes for sale has remained near

low levels.

Business investment has continued to

rebound . . .

Real outlays for business investment—that

is, private nonresidential xed investment—

rose at an annual rate of about 6percent

in the second half of 2017, a bit below the

gain in the rst half but still notably faster

than the unusually weak pace recorded

in 2016 (gure21). Business spending on

equipment and intangibles (such as research

Consumer sentiment

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

Index

50

60

70

80

90

2018201620142012201020082006

Diffusion index

18. Indexes of consumer sentiment and income expectations

Real income expectations

N

OTE

: The data extend through February 2018; the February data are

preliminary. The consumer sentiment data are monthly and are indexed to

100 in 1966. The real income expectations data are calculated as the net

percentage of survey respondents expecting family income to go up more

than prices during the next year or two plus 100 and are shown as a

three-month moving average.

S

OURCE

: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers.

200

+

_

0

200

400

600

800

1,000

Billions of dollars, annual rate

201720152013201120092007

17. Changes in household debt

Sum

NOTE

: The values for 2017 are the averages of the seasonally

adjusted

annualized quarterly flows through 2017:Q3.

S

OURCE: Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release Z.1,

“Financial

Accounts of the United States.”

Mortgages

Consumer credit

5.0

5.5

6.0

6.5

7.0

Ratio

20172014201120082005200219991996

16. Wealth-to-income ratio

Quarterly

NOTE

: The data extend through 2017:Q3. The series is the ratio of

household net worth to disposable personal income.

SOURCE: For net worth, Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release Z.1,

“Financial

Accounts of the United States”; for income, Bureau of Economic

Analysis via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2018 19

and development) advanced at a solid pace

in the second half of the year, and forward-

looking indicators of business spending are

generally favorable: Orders and shipments of

capital goods have posted net gains in recent

months, and indicators of business sentiment

and activity remain very upbeat. That said,

business outlays on structures turned down in

the second half of 2017, as investment growth

in drilling and mining structures retreated

from a very rapid pace in the rst half and

investment in other nonresidential structures

declined.

. . . while corporate nancing conditions

have remained accommodative

Aggregate ows of credit to large nonnancial

rms remained solid through the third

quarter, supported in part by continued low

interest rates (gure22). The gross issuance

of corporate bonds stayed robust during

the second half of 2017, and yields on both

investment-grade and high-yield corporate

bonds remained low by historical standards

(gure23).

Despite solid growth in business investment,

outstanding commercial and industrial (C&I)

loans on banks’ books continued to rise

only modestly in the third quarter of 2017.

Respondents to the Senior Loan Ocer

Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices,

or SLOOS, reported that demand for C&I

loans declined in the third quarter and was

little changed in the fourth quarter even as

lending standards and terms on such loans

eased.

8

Respondents attributed this decline in

demand in part to rms drawing on internally

generated funds or using alternative sources

of nancing. Financing conditions for small

businesses appear to have remained favorable,

and although credit growth has remained

sluggish, survey data suggest this sluggishness

is largely due to continued weak demand for

credit by small businesses.

8. The SLOOS is available on the Board’s website at

https://www.federalreserve.gov/data/sloos/sloos.htm.

Existing home sales

.2

.4

.6

.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

Millions, annual rate

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

6.5

7.0

7.5

2018201620142012201020082006

19. New and existing home sales

Millions, annual rate

New home sales

N

OTE

: Data are monthly. New home sales extend through December

2017

and include only single-family sales. Existing home sales

includes

single-family, condo, townhome, and co-op sales.

S

OURCE

: For new home sales, U.S. Census Bureau; for existing

home

sales, National Association of Realtors; all via Haver Analytics.

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

15

Percent, annual rate

20172016201520142013201220112010

21. Change in real private nonresidential fixed investment

H1

H2

SOURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Structures

Equipment and intangible capital

Multifamily starts

Single-family permits

0

.4

.8

1.2

1.6

2.0

Millions of units, annual rate

2018201620142012201020082006

20. Private housing starts and permits

Monthly

Single-family starts

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau via Haver Analytics.

20 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Net exports subtracted from GDP

growth in the fourth quarter after

providing a modest addition during the

rest of the year

U.S. real exports expanded at a moderate

pace in the second half of last year after

having increased more rapidly in the rst half,

supported by solid foreign growth (gure24).

At the same time, real imports surged in the

fourth quarter following a slight contraction in

the third quarter. As a result, real net exports

moved from modestly lifting U.S. real GDP

growth during the rst three quarters of 2017

to subtracting more than 1percentage point in

the fourth quarter. Although the nominal trade

and current account decits narrowed in the

third quarter of 2017, the trade decit widened

in the fourth quarter (gure25).

Federal scal policy actions had a

roughly neutral effect on economic

growth in 2017 . . .

Federal government purchases rose 1percent

in 2017, and policy actions had little eect on

federal taxes or transfers (gure26). Under

currently enacted legislation, which includes

the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and the

Bipartisan Budget Act, federal scal policy

will likely provide a moderate boost to GDP

growth this year.

9

The federal unied decit continued to widen

in scal year 2017, reaching 3½percent of

nominal GDP. Although expenditures as a

share of GDP were relatively stable at a little

under 21percent, receipts moved lower in 2017

to roughly 17percent of GDP (gure27).

The ratio of federal debt held by the public

to nominal GDP was 75¼percent at the end

of scal year 2017 and remains quite elevated

relative to historical norms (gure28).