PHYSICIAN’S GU IDE TO

Assessing and Counseling

Older Drivers

2nd edition

The information in this guide is provided to assist physicians in evaluating

the ability of their older patients to operate motor vehicles safely as part of

their everyday, personal activities. Evaluating the ability of patients to operate

commercial vehicles or to function as professional drivers involves more

stringent criteria and is beyond the scope of this publication.

This guide is not intended as a standard of medical care, nor should it be used

as a substitute for physicians’ clinical judgement. Rather, this guide reects the

scientic literature and views of experts as of December 2009, and is provided

for informational and educational purposes only. None of this guide’s materials

should be construed as legal advice nor used to resolve legal problems. If legal

advice is required, physicians are urged to consult an attorney who is licensed to

practice in their state.

Material from this guide may be reproduced. However, the authors of this

guide strongly discourage changes to the content, as it has undergone rigorous,

comprehensive review by medical specialists and other experts in the eld of

older driver safety.

The American Medical Association is accredited by the Accreditation Council

for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education

(CME) for physicians.

The American Medical Association designates this educational activity for a

maximum of 6.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should only claim

credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Additional copies of the guide can be downloaded or ordered online at the

AMA’s Older Driver’s Project Web site: www.ama-assn.org/go/olderdrivers.

For further information about the guide,

please contact:

Joanne G. Schwartzberg, MD

Director, Aging and Community Health

American Medical Association

515 N. State Street

Chicago, IL 60654

Physician’s Guide

to Assessing and

Counseling Older Drivers

An AMA Continuing Education Program

First Edition Original Release Date–7/30/2003

Second Edition–2/3/2010

Expiration Date–2/3/2012

Accreditation Statement

The American Medical Association is accredited

by the Accreditation Council for Continuing

Medical Education to provide continuing medical

education for physicians.

Designation Statement

The American Medical Association designates

this educational activity for a maximum of 6.25

AMA PRA Category 1 Credits

TM

. Physicians

should only claim credit commensurate with the

extent of their participation in the activity.

Disclosure Statement

The content of this activity does not relate to

any product of a commercial interest as dened

by the ACCME; therefore, there are no relevant

nancial relationships to disclose.

Educational Activity Objectives

• Increase physician awareness of the safety risks

of older drivers as a public health issue

• Identify patients who may be at risk for unsafe

driving

• Use various clinical screens to assess patients’

level of function for driving tness

• Employ referral and treatment options for

patients who are no longer t to drive

• Practice counseling techniques for patients who

are no longer t to drive

• Demonstrate familiarity with State reporting

laws and legal/ethical issues surrounding

patients who may not be safe on the road

Instructions for claiming AMA PRA

Category 1 Credits™

To facilitate the learning process, we encourage

the following method for physician participation:

Read the material in the Physician’s Guide to

Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers, complete

the CME Questionnaire & Evaluation, and then

mail both of them to the address provided. To

earn the maximum 6.25 AMA PRA Category 1

Credits™ , 70 percent is required to pass and

receive the credit.

IV Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

This Physician’s Guide to Assessing and

Counseling Older Drivers is the product

of a cooperative agreement between

the American Medical Association and

the National Highway Trafc Safety

Administration.

First edition: Primary Authors

Claire C. Wang, MD

American Medical Association

Catherine J. Kosinski, MSW

American Medical Association

Joanne G. Schwartzberg, MD

American Medical Association

Anne Shanklin, MA

American Medical Association

Second edition:

Principal Faculty Authors

Editor: David B. Carr, MD

Associate Professor of Medicine and

Neurology Washington University at

St. Louis Clinical Director

Planning Committee:

David B. Carr, MD;

Associate Professor of Medicine and

Neurology Washington University at

St. Louis Clinical Director

Joanne G. Schwartzberg, MD

Director, Aging and Community Health,

American Medical Association

Lela Manning, MPH, MBA

Project Coordinator, American Medical

Association

Jessica Sempek, MS

Program Administrator, American Medical

Asscoiation

Citation

Carr DB; Schwartzberg JG; Manning

L; Sempek J; Physician’s Guide to

Assessing and Counseling Older

Drivers, 2nd edition, Washington,

D.C. NHTSA. 2010.

This guide beneted signicantly

from the expertise of the following

individuals who served as reviewers

in this project.

Second edition: Content Consultants

Lori C. Cohen

AARP

Senior Project Manager, Driver Safety

Jami Croston, OTD

Washington University at St. Louis

T. Bella Dinh-Zarr, PhD, MPH

Road Safety Director, FIA Foundation

North American Director, MAKE

ROADS SAFE–The Campaign for Global

Road Safety

John W. Eberhard, PhD

Consultant, Aging and Senior

Transportation Issues

Camille Fitzpatrick, MSN, NP

University of California Irvine

Clinical Professor Family Medicine

Mitchell A. Garber, MD,

MPH, MSME

National Transportation Safety Board

Medical Ofcer

Anne Hegberg, MS, OTR/L

Marionjoy Rehabilitation Hospital

Certied Driver Rehabilitation Specialist

Patti Y. Horsley, MPH

Center for Injury Prevention

Policy and Practice

SDSU EPIC Branch

California Department of Public Health

Linda Hunt, OTR/L, PhD

Pacic University

School of Occupational Therapy

Associate Professor

Jack Joyce

Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration

Driver Safety Research Ofce

Senior Research Associate

Karin Kleinhans OTR/L

Sierra Nevada Memorial Hospital

Center for Injury Prevention Policy &

Practice

Occupational Therapy Association of

California

Kathryn MacLean, MSW

St. Louis University

Mangadhara R. Madineedi, MD, MSA

Harvard Medical School

Instructor in Medicine

VA Boston Healthcare System

Director, Geriatrics & Extended Care

Service Line

Richard Marottoli, MD, MPH

American Geriatrics Society

John C. Morris

Professor of Neurology

Washington University School of Medicine

Germaine L. Odenheimer, MD

VAMC

Donald W. Reynolds Department of

Geriatric Medicine

Associate Professor

Alice Pomidor, MD, MPH

Florida State University College of

Medicine

Associate Professor, Department of

Geriatrics

Kanika Mehta Rankin

Loyola University Chicago School of Law

(2nd year) Juris Doctorate Candidate,

2011

Yael Raz, MD

American Academy of Otolaryngology

William H. Roccaforte, MD

American Association for Geriatric

Psychiatry

Nebraska Medical Center

Department of Psychiatry

Gayle San Marco, OTR/L, CDRS

Northridge Hospital Medical Center

Project Consultation, Center for Injury

Prevention Policy & Practice

Freddie Segal-Gidan, PA-C, PhD

American Geriatrics Society

William Shea, OTR/L

Fairlawn Rehabilitation Hospital

VAcknowledgements

Patricia E. Sokol, RN, JD

Senior Poilcy Analyst, Patient Safety

American Medical Association

Esther Wagner, MA

National Highway Trafc Safety

Administration

First edition: Advisory Panel

Sharon Allison-Ottey, MD

National Medical Association

Joseph D. Bloom, MD

American Psychiatric Association

Audrey Rhodes Boyd, MD

American Academy of Family Physicians

David B. Carr, MD

Washington University School of Medicine

Bonnie M. Dobbs, PhD

University of Alberta

Association for the Advancement of

Automotive Medicine

John Eberhard, PhD

National Highway Trafc Safety

Administration

Laurie Flaherty, RN, MS

National Highway Trafc Safety

Administration

Arthur M. Gershkoff, MD

American Academy of Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation

Brian Greenberg, MEd

American Association of Retired Persons

Lynne M. Kirk, MD, FACP

American College of Physicians –

American Society of Internal Medicine

Marian C. Limacher, MD, FACC,

FSGC

American College of Cardiology

Society of Geriatric Cardiology

Richard Marottoli, MD, MPH

American Geriatrics Society

Lylas G. Mogk, MD

American Academy of Ophthalmology

John C. Morris, MD

American Academy of Neurology

Alzheimer’s Association

James O’Hanlon, PhD

Tri-Counties Regional Center

Cynthia Owsley, PhD, MSPH

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Robert Raleigh, MD

Maryland Department of Transportation

William Roccaforte, MD

American Association for Geriatric

Psychiatry

Jose R. Santana Jr., MD, MPH

National Hispanic Medical Association

Melvyn L. Sterling, MD, FACP

Council on Scientic Affairs

American Medical Association

Jane Stutts, PhD

University of North Carolina Highway

Safety Research Center

First edition: Review Committee

Geri Adler, MSW, PhD

Minneapolis Geriatric Research Education

Clinical Center

Reva Adler, MD

American Geriatrics Society

Elizabeth Alicandri

Federal Highway Administration

Paul J. Andreason, MD

Food and Drug Administration

Mike Bailey

Oklahoma Department of Public Safety

Robin Barr, PhD

National Institute on Aging

Arlene Bierman, MD, MS

Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality

Carol Bodenheimer, MD

American Academy of Physical Medicine

and Rehabilitation

Jennifer Bottomley, PhD, MS, PT

American Physical Therapy Association

Thomas A. Cavalieri, DO

American Osteopathic Association

Lori Cohen

American Association of Motor Vehicle

Administrators

Joseph Coughlin, PhD

Gerontological Society of America

T. Bella Dinh-Zarr, PhD, MPH

AAA

Barbara Du Bois, PhD

National Resources Center on Aging

and Injury

Leonard Evans, PhD

Science Serving Society

Connie Evaschwick, ScD., FACHE

American Public Health Association

Jeff Finn, MA

American Occupational Therapy

Association

Jaime Fitten, MD

UCLA School of Medicine

Marshall Flax, MA

Association for the Education and

Rehabilitation of the Blind and

Visually Impaired

Linda Ford, MD

Nebraska Medical Association

Barbara Freund, PhD

Eastern Virginia Medical School

Mitchell Garber, MD, MPH, MSME

National Transportation Safety Board

Andrea Gilbert, COTA/L

Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago

Claudia Grimm, MSW

Oregon Department of Transportation

Kent Higgins, PhD

Lighthouse International

VI Acknowledgements

Linda Hunt, PhD, OTR/L

Maryville University

Mary Janke, PhD

California Department of Motor Vehicles

Gary Kay, PhD

Washington Neuropsychological Institute

Shara Lynn Kelsey

Research and Development

California Department of Motor Vehicles

Susan Kirinich

National Highway Trafc Safety

Administration

Donald Kline, PhD

University of Calgary

Philip LePore, MS

New York State Ofce for the Aging

Sandra Lesikar, PhD

US Army Center for Health Promotion

and Preventive Medicine

William Mann, OTR, PhD

University of Florida

Dennis McCarthy, MEd, OTR/L

University of Florida

Gerald McGwin, PhD

University of Alabama

Michael Mello, MD, FACEP

American College of Emergency Physicians

Barbara Messinger-Rapport, MD, PhD

Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Alison Moore, MD, MPH

American Public Health Association

David Geffen School of Medicine,

University of California

Anne Long Morris, EdD, OTR/L

American Society on Aging

Germaine Odenheimer, MD

Center for Assessment and Rehabilitation

of Elderly Drivers

Eli Peli, M.Sc., OD

Schepens Eye Research Institute

Alice Pomidor, MD, MPH

Society of Teachers of Family Medicine

George Rebok, MA, PhD

Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and

Public Health

Selma Sauls

Florida Department of Highway Safety and

Motor Vehicles

Susan Samson

Pinellas/Pasco Area Agency on Aging

Steven Schachter, MD

Epilepsy Foundation

Frank Schieber, PhD

University of South Dakota

Freddi Segal-Gidan, PA, PhD

American Geriatrics Society

Melvin Shipp, OD, MPH, DrPh

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Richard Sims, MD

American Geriatrics Society

Kristen Snyder, MD

Oregon Health & Science University

School of Medicine

Susan Standfast, MD, MPH

American College of Preventative Medicine

Holly Stanley, MD

American Geriatrics Society

Loren Staplin, PhD

Transanalytics and Texas Transportation

Institute

Wendy Stav, PhD, OTR, CDRS

American Occupational Therapy

Association

Cleveland State University

Donna Stressel, OTR, CDRS

Association of Driver Rehabilitation

Specialists

Cathi A. Thomas, RN, MS

Boston University Medical Center

American Parkinson Disease Association

John Tongue, MD

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery

Patricia Waller, PhD

University of Michigan

Lisa Yagoda, MSW, ACSW

National Association of Social Workers

Patti Yanochko, MPH

San Diego State University

Richard Zorowitz, MD

National Stroke Association

VIITable of Contents

Table of Contents

Preface .................................................................................................................................. IX

Chapter 1 .................................................................................................................................1

Safety and the Older Driver With Functional or Medical Impairments: An Overview

Chapter 2 ...............................................................................................................................11

Is the Patient at Increased Risk for Unsafe Driving?

Red Flags for Further Assessment

Chapter 3 ...............................................................................................................................19

Assessing Functional Ability

Chapter 4 ...............................................................................................................................33

Physician Interventions

Chapter 5 ...............................................................................................................................41

The Driver Rehabilitation Specialist

Chapter 6 ...............................................................................................................................49

Counseling the Patient Who is no Longer Safe to Drive

Chapter 7 ...............................................................................................................................59

Ethical and Legal Responsibilities of the Physician

Chapter 8 ...............................................................................................................................69

State Licensing and Reporting Laws

Chapter 9 .............................................................................................................................145

Medical Conditions and Medications That May Affect Driving

Chapter 10 ...........................................................................................................................187

Moving Beyond This Guide: Future Plans to Meet the Transportation Needs of Older Adults

Appendix A ..........................................................................................................................197

CPT

®

Codes

VIII Table of Contents

Table of Contents (continued)

Appendix B ..........................................................................................................................201

Patient and Caregiver Educational Materials

Am I a Safe Driver? ....................................................................................................................... 203

Successful Aging Tips .................................................................................................................. 205

Tips for Safe Driving ...................................................................................................................... 207

How to Assist the Older Driver ...................................................................................................... 209

Getting By Without Driving ............................................................................................................ 213

Where Can I Find More Information? ............................................................................................. 215

Appendix C ..........................................................................................................................221

Continuing Medical Education Questionnaire and Evaluation

Physicians Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers ....................................................... 221

Continuing Medical Education Evaluation Form ............................................................................. 224

Index ....................................................................................................................................229

IXPreface

Preface

The science of public health and the practice of medicine are often deemed two

separate entities. After all, the practice of medicine centers on the treatment of

disease in the individual, while the science of public health is devoted to preven-

tion of disease in the population. However, physicians can actualize public health

priorities through the delivery of medical care to their individual patients.

One of these priorities is the prevention of injury. More than 400 Americans

die each day as a result of injuries sustained from motor vehicle crashes, rearms,

poisonings, suffocation, falls, res, and drowning. The risk of injury is so great

that most people sustain a signicant injury at some time during their lives.

The Physician’s Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers was created by

the American Medical Association (AMA), with support from the National

Highway Trafc and Safety Administration (NHTSA), to help physicians

address preventable injuries—in particular, those incurred in motor vehicle

crashes. Currently, motor vehicle injuries are the leading cause of injury-related

deaths among 65- to 74-year-olds and are the second leading cause (after falls)

among 75- to 84-year-olds. While trafc safety programs have reduced the fatal-

ity rate for drivers under age 65, the fatality rate for older drivers has consistently

remained high. Clearly, additional efforts are needed.

Physicians are in a leading position to address and correct this health disparity.

By providing effective health care, physicians can help their patients maintain

a high level of tness, enabling them to preserve safe driving skills later in life

and protecting them against serious injuries in the event of a crash. By adopting

preventive practices—including the assessment and counseling strategies outlined

in this guide—physicians can better identify drivers at risk for crashes, help

enhance their driving safety, and ease the transition to driving retirement if

and when it becomes necessary.

Through the practice of medicine, physicians have the opportunity to promote

the safety of their patients and of the public. The AMA and NHTSA urge you

to use the tools in this Physician’s Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers

to forge a link between public health and medicine.

The project was supported by cooperative agreement number DTNH22-08-H-00185

from the National Highway Trafc Safety Administration (NHTSA) of the Department

of Transportation. While this guide was reviewed by NHTSA, the contents of this guide

are those of the authors and do not represent the opinions, policies or ofcial positions

of NHTSA.

CHAPTER 1

Safety and the Older Driver

With Functional or Medical

Impairments: An Overview

1

Chapter 1—Safety and the Older Driver With Functional or Medical Impairments: An Overview

Patients like Mrs. Simon and Mr. Evans

are becoming more common in physi-

cians’ practices. Buoyed by the large

ranks of “baby boomers” and increased

life expectancy, the U.S. older adult

population is growing nearly twice as

fast as the total population.

1,2

Within

this cohort of older adults, an increasing

proportion will be licensed to drive, and

it is expected that these license-holders

will drive more miles than older drivers

do today.

3

As the number of older drivers with

medical conditions expands, patients

and their families will increasingly

turn to physicians for guidance on safe

driving. Physicians will have the chal-

lenge of balancing their patients’ safety

against their transportation needs and

the safety of society.

This guide is intended to help you

answer the questions, “At what level of

severity do medical conditions impair

safe driving?” “What can I do to help

my patient drive more safely?”

*

, and if

necessary to help you counsel patients

1. National Center for Statistics & Analysis.

Trafc Safety Facts 2000: Older Population.

DOT HS 809 328. Washington, DC: National

Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

2. Population Projections of the United States by

Age, Sex, Race, Hispanic, Origin, and Nativity:

1999 to 2100. Population Projections Program,

Population Division, Census Bureau Internet

release date: January 13, 2000. Revised date:

February 14, 2000. Suitland, MD: U.S.

Census Bureau.

3. Eberhard, J. Safe Mobility for Senior Citizens.

International Association for Trafc and Safety

Services Research. 20(1):29–37.

Mrs. Simon, a 67-year-old woman

with type 2 diabetes mellitus and

hypertension, mentions during a

routine check-up that she almost

hit a car while making a left-hand

turn when driving two weeks ago.

Although she was uninjured, she

has been anxious about driving since

that episode. Her daughter has

called your ofce expressing concern

about her mother’s driving abilities.

Mrs. Simons admits to feeling less

condent when driving and wants

to know if you think she should stop

driving. What is your opinion?

Mr. Evans, a 72-year-old man

with coronary artery disease and

congestive heart failure, arrives for

an ofce visit after fainting yesterday

and reports complaints of “light-

headedness” for the past two weeks.

When feeling his pulse, you notice

that his heartbeat is irregular. You

perform a careful history and physi-

cal examination, and order some

laboratory tests to help determine the

cause of his atrial brillation. When

you ask Mr. Evans to schedule a

follow-up appointment for the next

week, he tells you he cannot come

at that time because he is about to

embark on a two-day road trip to

visit his daughter and newborn

grandson. Would you address the

driving issue and if so, how?

What would you communicate to

the patient?

CHAPTER 1

Safety and the Older

Driver With Functional

or Medical Impairments

An Overview

about driving cessation and alternate

means of transportation. Mobility

counseling and discussing alternative

modes of transportation need to take a

more prominent role in the physician’s

ofce. To these ends, we have reviewed

the scientic literature and collaborated

with clinicians and experts in this eld

to produce the following physician tools:

• An ofce-based assessment of

medical tness to drive. This

assessment is outlined in the

algorithm, Physician’s Plan for

Older Drivers’ Safety (PPODS),

presented later in this chapter.

• A functional assessment battery,

the Assessment of Driving Related

Skills (ADReS). This can be found

in Chapter 3.

• A reference table of medical

conditions and medications that

may affect driving, with specic

recommendations for each, can

be found in Chapter 9.

In addition to these tools, we also

present the following resources:

• Information to help you navigate

the legal and ethical issues regarding

patient driving safety. Information

* Please be aware that the information in this

guide is provided to assist physicians in evaluat-

ing the ability of their older patients to operate

motor vehicles safely as part of their everyday,

personal activities. Evaluating the ability of

patients to operate commercial vehicles or to

function as professional drivers involves more

stringent criteria and is beyond the scope of this

guide.

2 Chapter 1—Safety and the Older Driver With Functional or Medical Impairments: An Overview

on patient reporting, with a state-by-

state list of licensing criteria, license

renewal criteria, reporting laws,

and Department of Motor Vehicles

(DMV) contact information, can be

found in Chapters 7 and 8.

• Recommended Current Procedural

Terminology (CPT

®

) codes for

assessment and counseling procedures.

These can be found in Appendix A.

• Handouts for your patients and their

family members. These handouts,

located in Appendix B, include a self-

screening tool for driving safety, safe

driving tips, driving alternatives, and

a resource sheet for concerned family

members. These handouts can be

removed from the guide and photo-

copied for distribution to patients

and their family members.

We understand that physicians may

lack expertise in communicating with

patients about driving, discussing the

need for driving cessation (delivering

bad news), and being aware of viable

alternative transportation options to

offer. Physicians also may be concerned

about dealing with the patient’s anger,

or even losing contact with the patient.

Driving is a sensitive subject, and the

loss of driving privileges can be stressful.

While these are reasonable concerns,

there are ways to minimize the impact

on the doctor-patient relationship when

discussing driving. We provide sample

approaches in subsequent chapters in

the areas of driving assessment, rehabili-

tation, restriction, and cessation.

We want this information to be

readily accessible to you and your

ofce staff. You can locate this guide

on the Internet at the AMA Web site

(www.ama-assn.org/go/olderdrivers).

Additional printed copies may also

be ordered through the Web site.

Before you read the rest of the guide,

you may wish to familiarize yourself

with key facts about older drivers.

Older drivers: Key facts

Fact #1: The number of older adult

drivers is growing rapidly and they

are driving longer distances.

Life expectancy is at an all-time high

4

and the older population is rap-

idly increasing. By the year 2030, the

population of adults older than 65 will

more than double to approximately 70

million, making up 20 percent of the

total U.S. population.

5

In many States,

including Florida and California, the

population of those over age 65 may

reach 20 percent in this decade The

fastest growing segment of the popula-

tion is the 80-and-older group, which

is anticipated to increase from about 3

million this year to 8 to 10 million over

the next 30 years. We can anticipate

many older drivers on the roadways

over the next few decades, and your

patients will likely be among them.

Census projections estimate that by

the year 2020 there will be 53 million

persons over age 65 and approximately

40 million (75%) of those will be

licensed drivers.

6

The increase in the

number of older drivers is due to many

factors. In addition to the general aging

of the population that is occurring in

all developed countries, many more

female drivers are driving into advanced

age. This will likely increase with aging

cohorts such as the baby boomers.

In addition, the United States has

become a highly mobile society, and

older adults are using automobiles for

volunteer activities and gainful employ-

ment, social and recreational needs,

and cross country travel. Recent studies

suggest that older adults are driving

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

2008. National Center for Health Statistics.

Accessed on December 14, 2008 at;

www.cdc.gov/nchs/PRESSROOM/

07newsreleases/lifeexpectancy.htm

5. U.S. Census Bureau, Healthy Aging, 2008.

Accessed on December 14, 2008 at; www.cdc.

gov/NCCdphp/publications/aag/aging.htm

6. U.S. Census Bureau. Projection of total resident

population by 5-year age groups and sex with

special age categories; middle series, 2016–2020.

Washington, DC: Population Projections

Program, Population Division, U.S. Census

Bureau; 2000.

more frequently, while transportation

surveys reveal an increasing number of

miles driven per year for each successive

aging cohort.

Fact #2: Driving cessation is inevi-

table for many and can be associated

with negative outcomes.

Driving can be crucial for performing

necessary chores and maintaining social

connectedness, with the latter having

strong correlates with mental and physi-

cal health.

7

Many older adults continue

to work past retirement age or engage in

volunteer work or other organized ac-

tivities. In most cases, driving is the pre-

ferred means of transportation. In some

rural or suburban areas, driving may be

the sole means of transportation. Just as

the driver’s license is a symbol of inde-

pendence for adolescents, the ability to

continue driving may mean continued

mobility and independence for older

drivers, with great effects on their qual-

ity of life and self-esteem.

8

In a survey of 2,422 adults 50 and older,

86 percent of survey participants report-

ed that driving was their usual mode of

transportation. Within this group, driv-

ing was the usual method of transporta-

tion for 85 percent of participants 75 to

79, 78 percent of participants 80 to 84,

and 60 percent of participant’s 85 and

older.

9

This data also indicates that the

probability of losing the ability to drive

increases with advanced age. It is esti-

mated that the average male will have

6 years without the functional ability to

drive a car and the average female will

have 10 years.

10

However, our society

has not prepared the public for driving

7. Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., & See-

man, T. E. From social integration to health:

Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med.

51:843–857.

8. Stutts, J. C. Do older drivers with visual and

cognitive impairments drive less? J Am Geriatr

Soc. 46(7):854–861.

9. Ritter, A. S., Straight, A., & Evans, E.

Understanding Senior Transportation: Report

and Analysis of a Survey of Consumers Age

50+. American Association for Retired Persons,

Policy and Strategy Group, Public Policy

Institute, p. 10–11.

10. Foley, D. J., Heimovitz, H. K., Guralnik, J., &

Brock, D. B. Driving life expectancy of persons

aged 70 years and older in the United States.

Am J Public Health. 92:1284–1289

3Chapter 1—Safety and the Older Driver With Functional or Medical Impairments: An Overview

cessation, and patients and physicians

are often ill-prepared when that time

comes.

Studies of driving cessation have noted

increased social isolation, decreased

out-of-home activities,

11

and an in-

crease in depressive symptoms.

12

These

outcomes have been well documented

and represent some of the negative con-

sequences of driving cessation. It is im-

portant for health care providers to use

the available resources and professionals

who can assist with transportation to

allow their patients to maintain inde-

pendence. These issues will be discussed

further in subsequent chapters.

Fact #3: Many older drivers

successfully self-regulate their

driving behavior.

As drivers age, they may begin to

feel limited by slower reaction times,

chronic health problems, and effects

from medications. Although transporta-

tion surveys over the years document

that the current cohort of older driv-

ers is driving farther, in later life many

reduce their mileage or stop driving

altogether because they feel unsafe or

lose condence. In 1990, males over 70

drove on average 8,298 miles, compared

with 16,784 miles for men 20 to 24; for

women, the gures were 3,976 miles

and 11,807 miles, respectively.

13

Older

drivers are more likely to wear seat belts

and are less likely to drive at night,

speed, tailgate, consume alcohol prior

to driving, and engage in other risky

behaviors.

14

Older drivers not only drive substan-

tially less, but also tend to modify

11. Marottoli, R. A., de Leon, C. F. M., & Glass,

T. A., et al. Consequences of driving cessation:

decreased out-of-home activity levels. J Gerontol

Series B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 55:S334–340.

12. Ragland, D. R., Satariano, W. A,. & MacLeod,

K. E. Driving cessation and increased depressive

symptoms J Gerontol Series A Bio Sci Med Sci.

60:399–403.

13. Evans, L. How safe were today’s older drivers

when they were younger? Am J Epidemiol.

1993;137(7);769–775.

14. Lyman, J. M., McGwin, G., &Sims, R.V. Factors

related to driving difculty and habits in older

drivers. Accid Anal Prev. 33:413–421.

when and how they drive. When they

recognize loss of ability to see well after

dark, many stop driving at night. There

are data that suggest older women are

more likely to self-regulate than men.

15

Others who understand the complex

demands of left turns at uncontrolled

intersections and their own diminished

capacity forgo left-hand turns, and

make a series of right turns instead. Self-

regulating in response to impairments

is simply a continuation of the strategy

we all employ daily in navigating this

dangerous environment—driving. Each

of us, throughout life, is expected to

use our best judgment and not operate

a car when we are impaired, whether

by fatigue, emotional distress, physical

illness, or alcohol. Thus, self-awareness,

knowledge of useful strategies, and

encouragement to use them may be

sufcient among cognitively intact

older adults; however, this remains an

important area for further study.

Older drivers may reduce their mile-

age by eliminating long highway trips.

However, local roads often have more

hazards in the form of signs, signals,

trafc congestion, and confusing inter-

sections. Decreasing mileage, then, may

not always proportionately decrease

safety risks.

16

In fact, the “low mileage”

drivers (e.g., less than 3,000 miles per

year) may actually be the group that is

most “at-risk.”

17

Despite all these self-regulating mea-

sures, motor vehicle crash rates per mile

driven begin to increase at age 65.

18

On

a case-by-case level, the risk of a crash

depends on whether each individual

driver’s decreased mileage and behavior

15. Kostyniuk, L. P., & Molnar, L. J. Self-regulatory

driving practices among older adults: health, age

and sex effects. Accid Anal Prev. 40: 1576–1580.

16. Janke, M. K. Accidents, mileage, and the exag-

geration of risk. Accid Anal Prev. 1991;23:183–

188.

17. Langford, J., Methorst, R., & Hakamies-

Blomqvist, L. Older drivers do not have a high

crash risk—a replication of low mileage bias.’

Accid Anal Prev. 38(3):574–578.

18. Li, G., Braver, E. R., & Chen, L. H. Exploring

the High Driver Death Rates per Vehicle-Mile

of Travel in Older Drivers: Fragility versus

Excessive Crash Involvement. Presented at the

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety; August

2001.

modications are sufcient to counter-

balance any decline in driving ability.

In some cases, decline—in the form of

peripheral vision loss, for example—

may occur so insidiously that the driver

is not aware of it until he/she experi-

ences a crash. In fact, a recent study

indicated that some older adults do not

restrict their driving despite having

signicant visual decits.

19

Reliance on

driving as the sole available means of

transportation can result in an unfortu-

nate choice between poor options. In

the case of dementia, drivers may lack

the insight to realize they are unsafe

to drive.

In a series of focus groups conducted

with older adults who had stopped

driving within the past ve years, about

40 percent of the participants knew

someone over age 65 who had problems

with his/her driving but was still behind

the wheel.

20

Clearly, some older drivers

require outside assessment and interven-

tions when it comes to driving safety.

Fact #4: The crash rate for older

drivers is in part related to physical

and/or mental changes associated

with aging and/or disease.

21

Compared with younger drivers whose

car crashes are often due to inexperi-

ence or risky behaviors,

22

older driver

crashes tend to be related to inattention

or slowed speed of visual processing.

23

Older driver crashes are often multiple-

vehicle events that occur at intersections

and involve left-hand turns. The crash is

usually caused by the older driver’s failure

to heed signs and grant the right-of-way.

At intersections with trafc signals, left-

19. Okonkwo, O. C., Crowe, M., Wadley, V. G.,

& Ball, K. Visual attention and self-regulation

of driving among older adults. Int Psychogeriatr.

20:162–173.

20. Persson, D. The elderly driver: deciding when to

stop. Gerontologist. 1993;33(1):88–91.

21. Preusser, D. F., Williams, A. F., Ferguson, S. A.,

Ullmer R. G., & Weinstein, H.B. Fatal crash

risk for older drivers at intersections. Accid Anal

Prev. 30(2):151–159.

22. Williams, A. F., & Ferguson, S. A. Rationale

for graduated licensing and the risks it should

address. Inj Prev. 8:ii9–ii16.

23. Eberhard, J. W. Safe Mobility for Senior

Citizens. International Association for Trafc

and Safety Sciences Research. 20(1):29–37.

4 Chapter 1—Safety and the Older Driver With Functional or Medical Impairments: An Overview

hand turns are a particular problem for

the older driver. At stop-sign-controlled

intersections, older drivers may not know

when to turn.

24

These driving behaviors indicate that

visual, cognitive, and/or motor factors

may affect the ability to drive in older

adults. Research has not yet determined

what percentage of older adult crashes

are due to driving errors that are also

common among middle-aged drivers,

what proportion are due to age-related

changes in cognition (such as delayed

reaction time), or how many could be

attributed to age-related medical illness-

es. However, it is believed that further

improvements in trafc safety will likely

result from improving driving perfor-

mance or modifying driving behavior.

25

The identication and management

of diseases has a potential to maintain

or improve driving abilities and

road safety.

Fact #5: Physicians can inuence

their patients’ decisions to modify

or stop driving. They can also help

their patients maintain safe

driving skills.

Although older drivers believe that

they should be the ones to make the

nal decision about driving, they also

agree that their physicians should advise

them. In a series of focus groups con-

ducted with older adults who had given

up driving, all agreed that the physi-

cians should talk to older adults about

driving, if a need exists. As one panelist

put it, “When the doctor says you can’t

drive anymore, that’s denite. But when

you decide for yourself, there might be

questions.” While family advice had

limited inuence on the participants,

most agreed that if their physicians

advised them to stop and their family

concurred, they would certainly retire

from driving.

26

This is consistent with a

24. Preusser, D. F., Williams, A. F., Ferguson, S. A.,

Ullmer, R. G., & Weinstein, H. B. Fatal crash

risk for older drivers at intersections. Accid Anal

Prev. 30(2):151–159.

25. Lee, J. D. Fifty years of driving safety research.

Hum Factors. 50: 521–528.

26. Persson, D. The elderly driver: deciding when to

stop. Gerontologist. 1993;33(1):88–91.

recent focus group study with caregivers

of demented drivers, who stated that

physicians should be involved in this

important decision-making process.

27

Physicians assist their older patients

to maintain safe mobility in two ways.

They provide effective treatment and

preventive health care, and they play a

role in determining the ability of older

adults to drive safely. Also, improved

cardiovascular and bone health has

the potential to reduce serious injuries

and improve the rate of recovery in the

event of a crash.

In many cases, physicians can keep

their patients on the road longer by

identifying and managing diseases, such

as cataracts and arthritis, or by discon-

tinuing sedating medications. Many

physicians are aware of the literature on

fall prevention, and that clinicians can

reduce future risks of falls and fractures

by addressing certain extrinsic (envi-

ronmental) and intrinsic factors.

28

Driv-

ing abilities share many attributes that

are necessary for successful ambulation,

such as adequate visual, cognitive, and

motor function. In fact, a history of falls

has been associated with an increased

risk of motor vehicle crash.

29

Brief physician intervention on topics

such as smoking and seat belt use has

been shown to be effective. There is

an assumption that doctors can and do

make a difference by evaluating older

individuals for medical tness to drive.

Furthermore, there is a crucial need to

have this hypothesis studied systemati-

cally. To date, little organized effort in

the medical community has been made

to help older adults improve or main-

tain their driving skills. Research and

clinical reviews on the assessment

27. Perkinson, M., Berg-Weger, M., Carr, D.,

Meuser, T., Palmer, J., Buckles, V., Powlishta,

K., Foley, D., & Morris, J. Driving and dementia

of the Alzheimer type: beliefs and cessation

strategies among stakeholders. Gerontologist.

45(5):676–685.

28. Tinetti, M. E. Preventing falls in elderly persons.

N Engl J Med. 348(1):42–49.

29. Margolis, K. L., Kerani, R. P., McGovern, P.,

et al. Risk factors for motor vehicle crashes in

older women. J Gerontol Series A Bio Sci Med Sci.

57:M186–M191.

of older drivers have focused on screen-

ing methods to identify unsafe drivers

and restrict older drivers. Physicians are

in a position to identify patients at risk

for unsafe driving or self-imposed driv-

ing cessation due to functional impair-

ments, and address and help manage

these issues to keep their patients driv-

ing safely for as long as possible.

Physicians must abide by State report-

ing laws. While the nal determination

of an individual’s ability to drive lies

with the driver licensing authority,

physicians can assist with this deter-

mination. Driver licensing regulations

and reporting laws vary greatly by State.

Some State laws are vague and open to

interpretation; therefore, it is impor-

tant for physicians to be aware of their

responsibilities for reporting unsafe

patients to the local driver licensing

authority. Information on State laws is

provided in Chapter 8.

Thus, physicians can play a more active

role in preventing motor vehicle crashes

by assessing their patients for medical

tness to drive, recommending safe

driving practices, referring patients to

driver rehabilitation specialists, advising

or recommending driving restrictions,

and referring patients to State authori-

ties when appropriate.

5Chapter 1—Safety and the Older Driver With Functional or Medical Impairments: An Overview

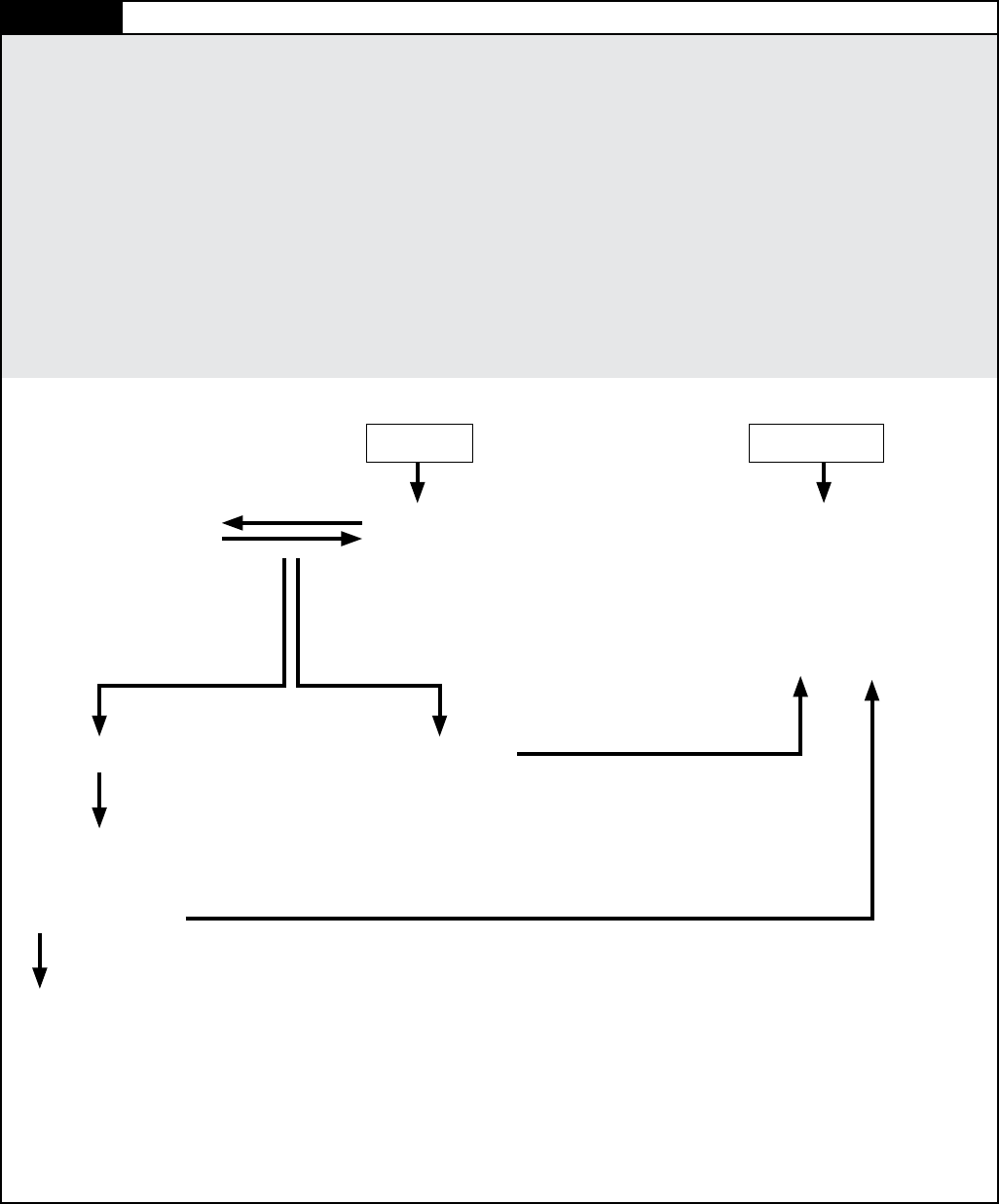

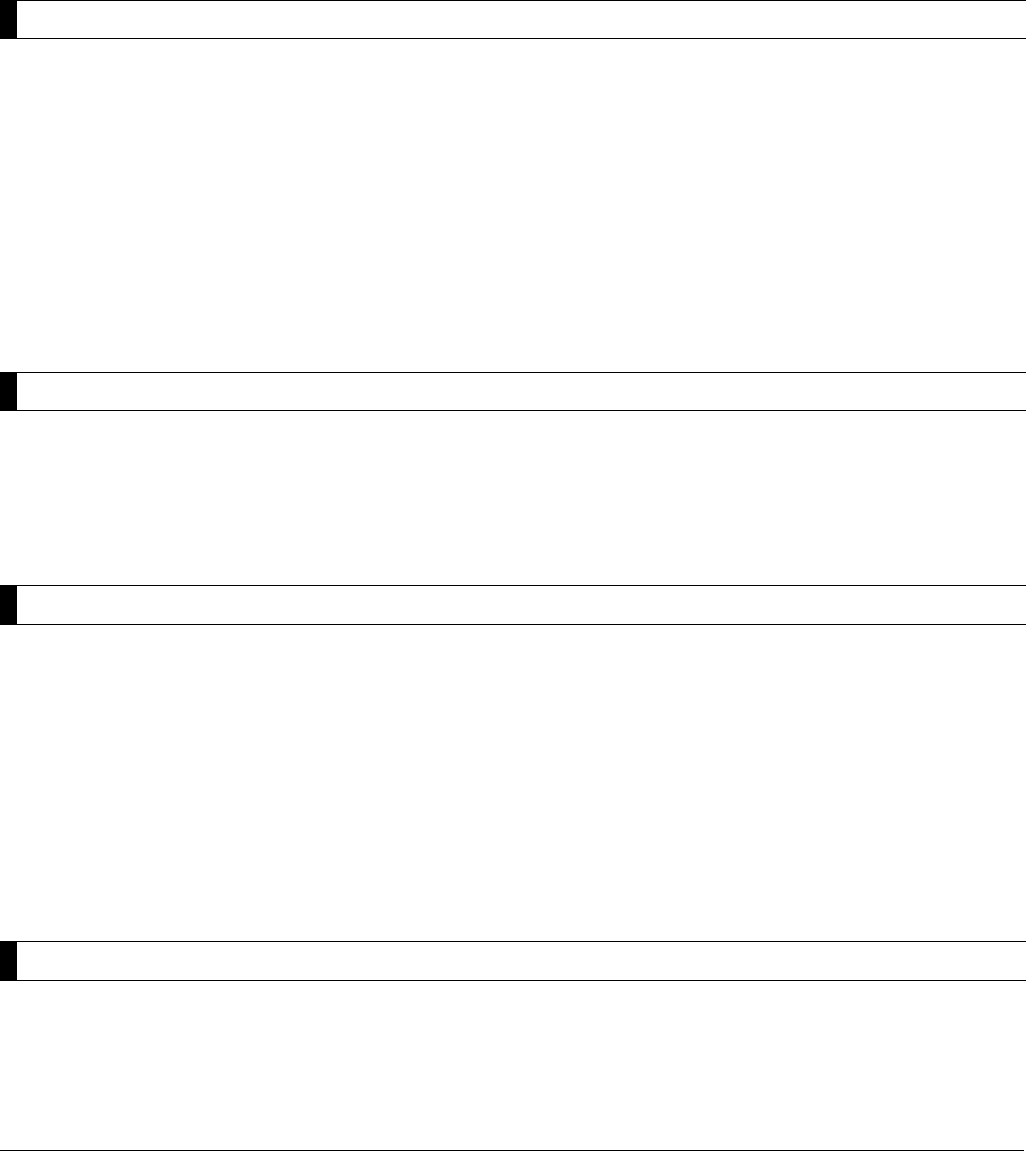

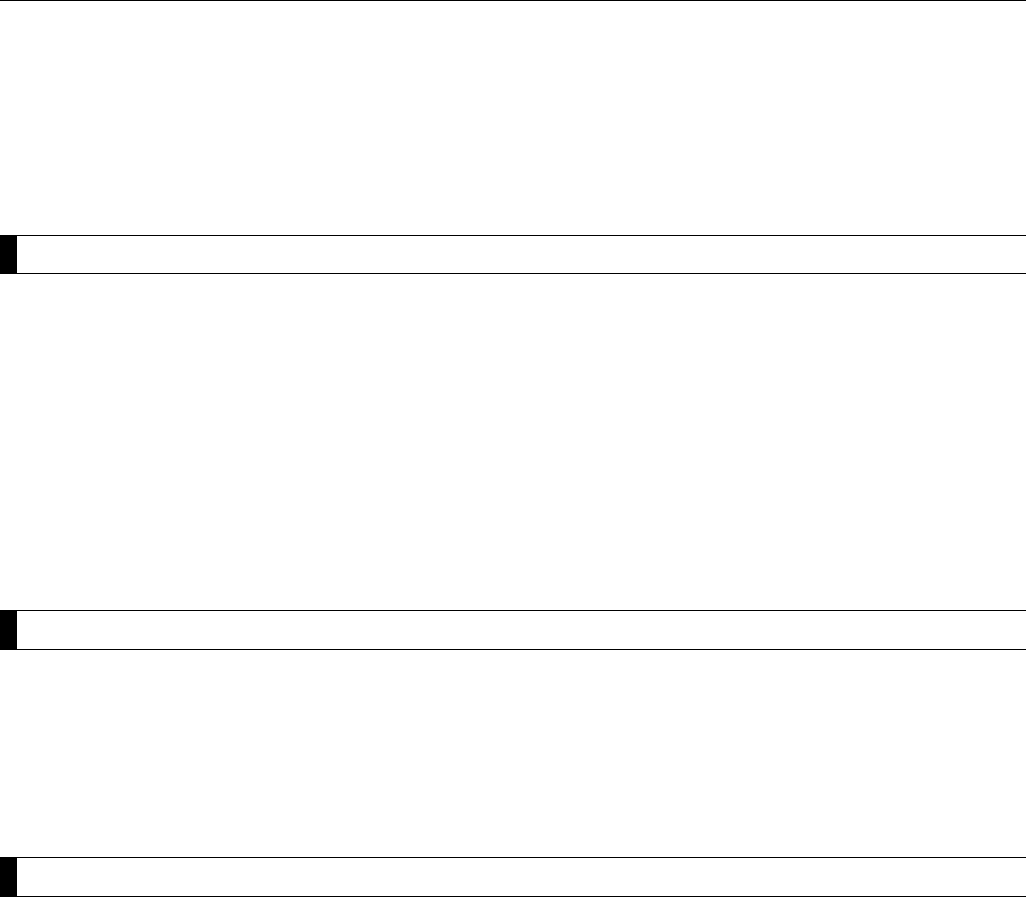

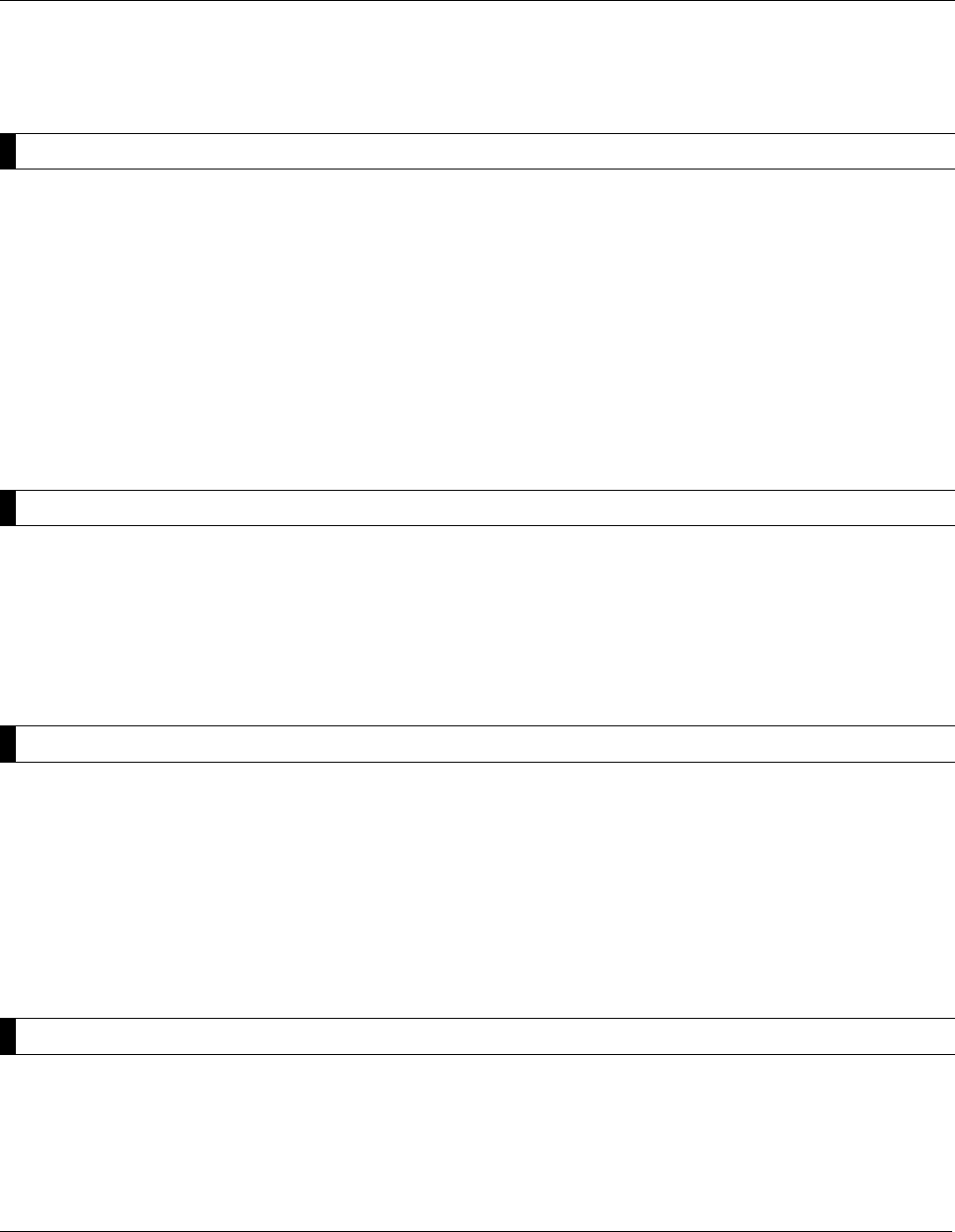

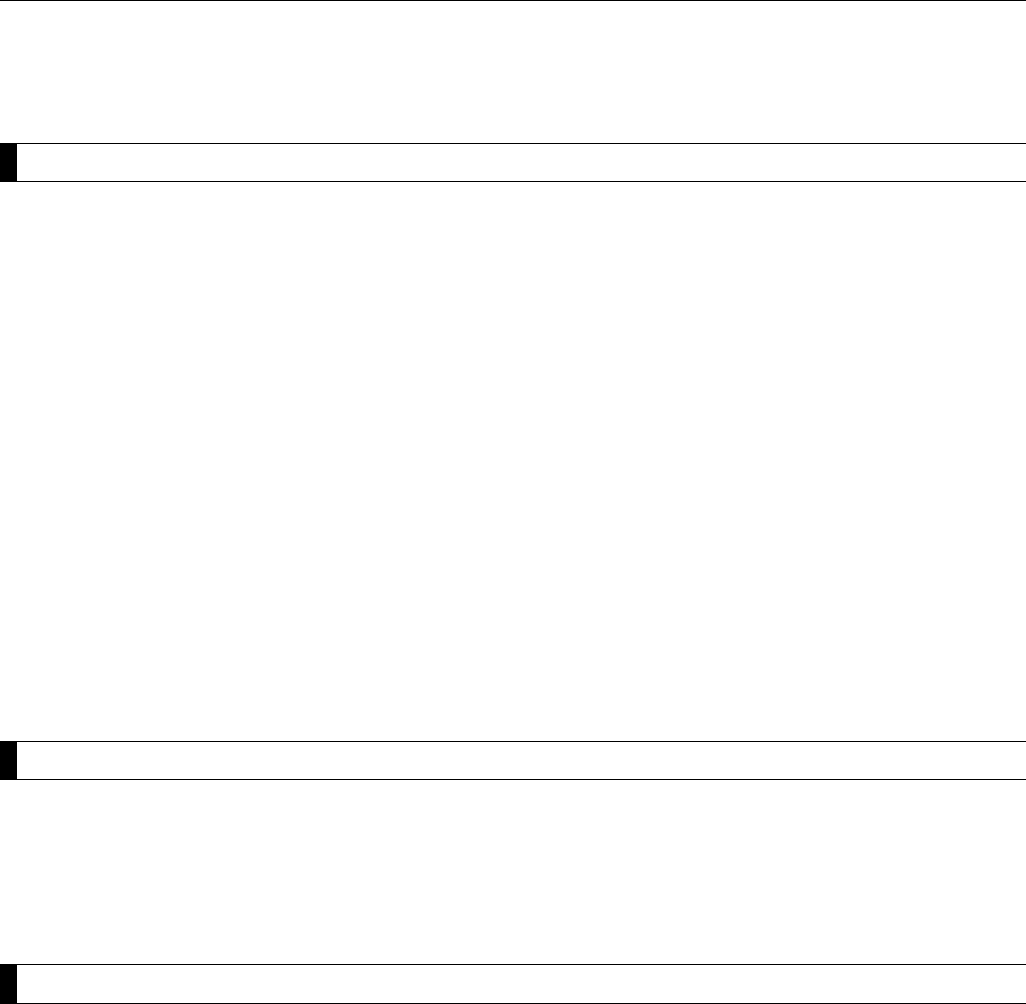

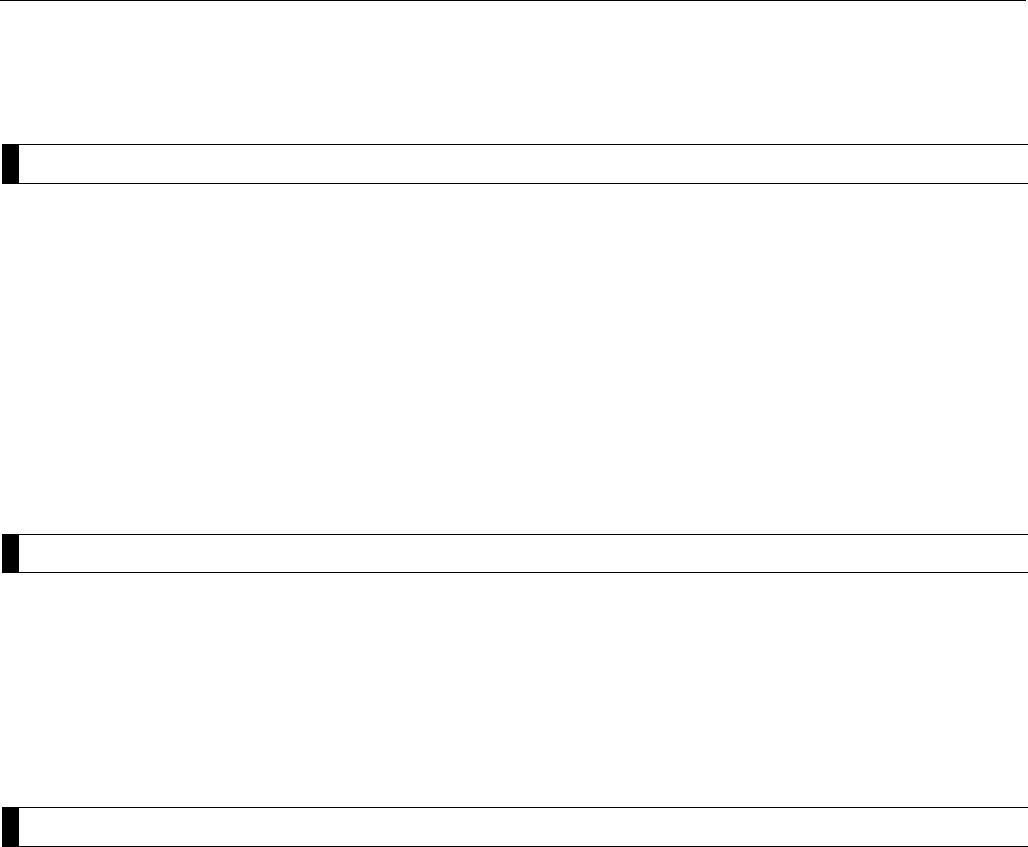

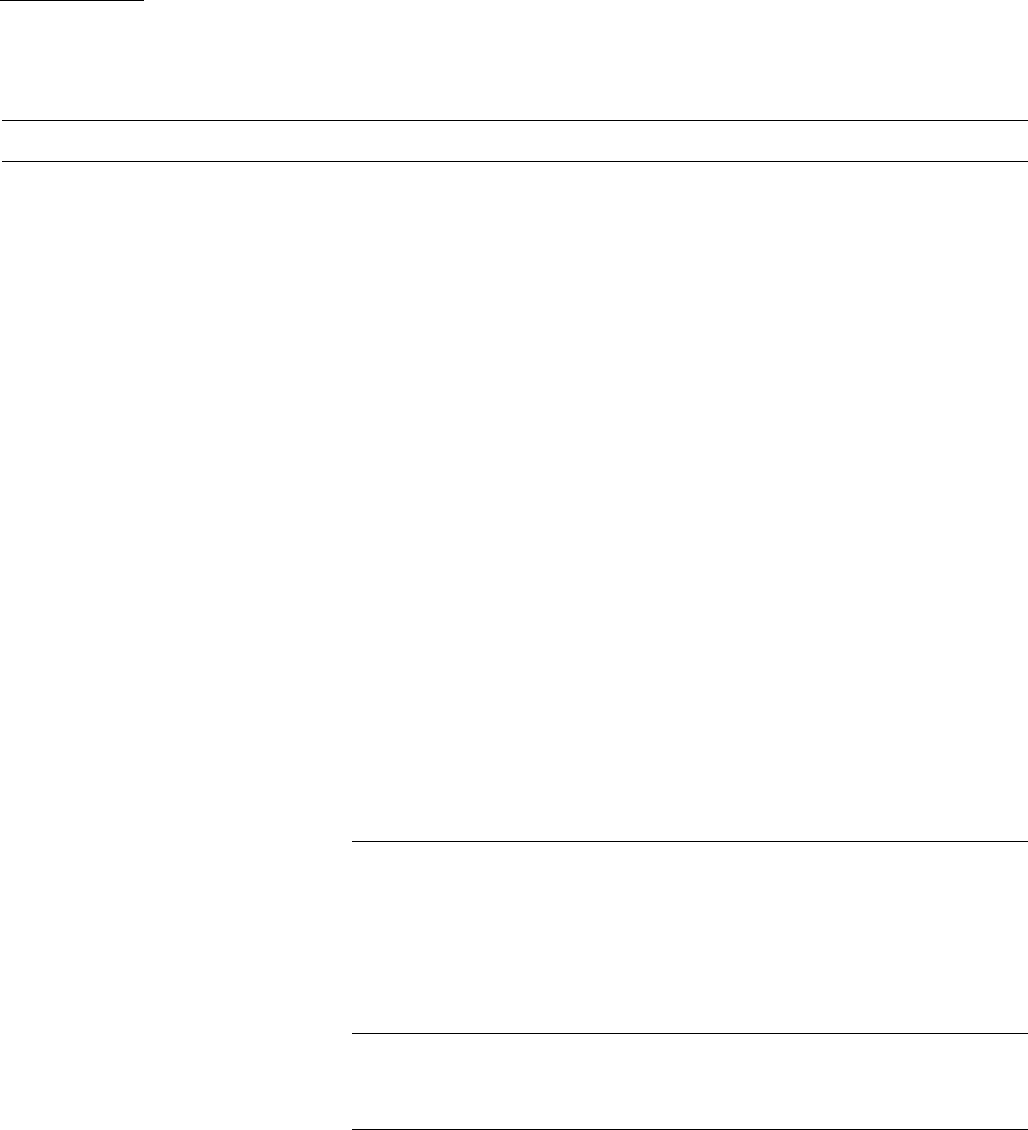

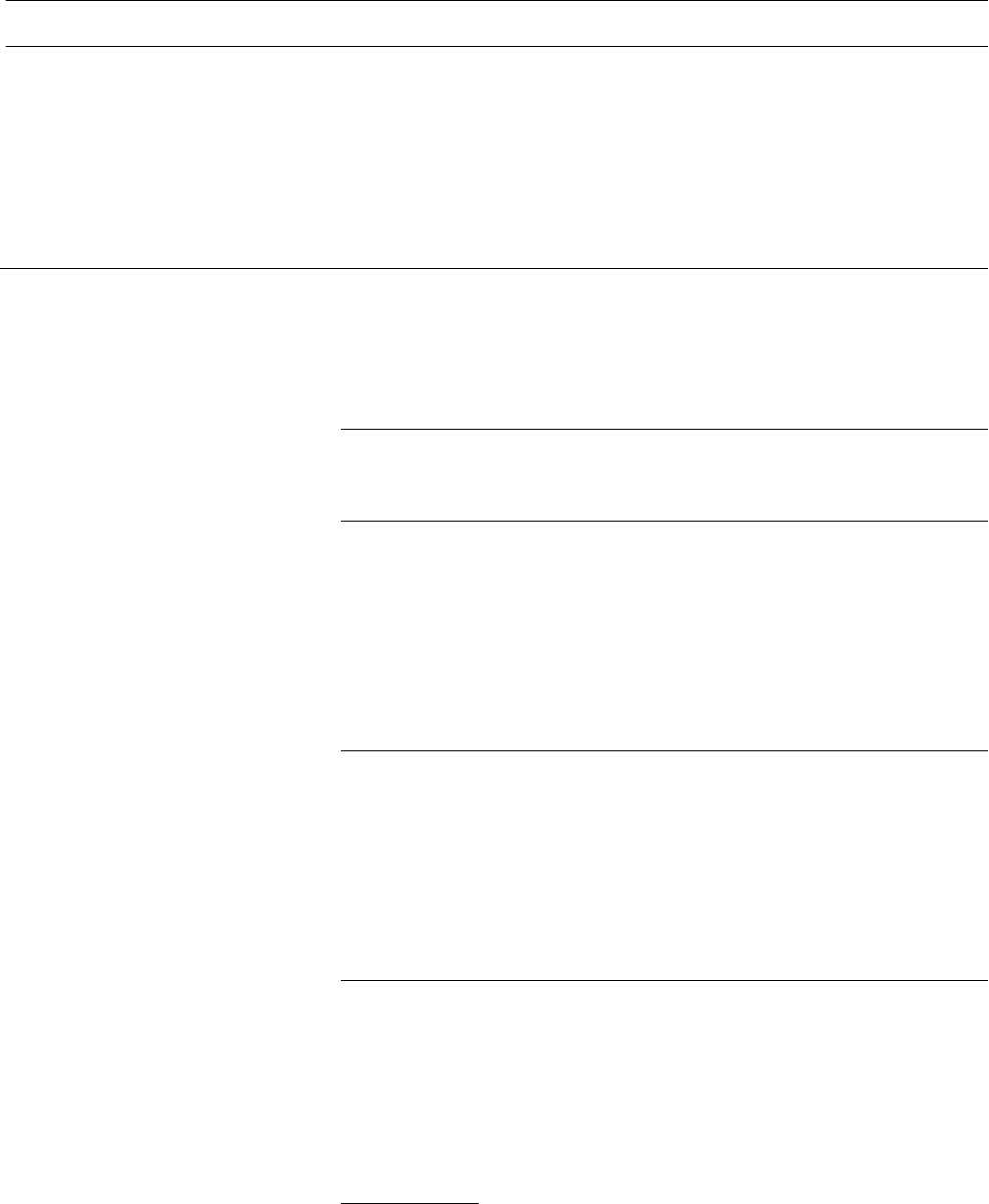

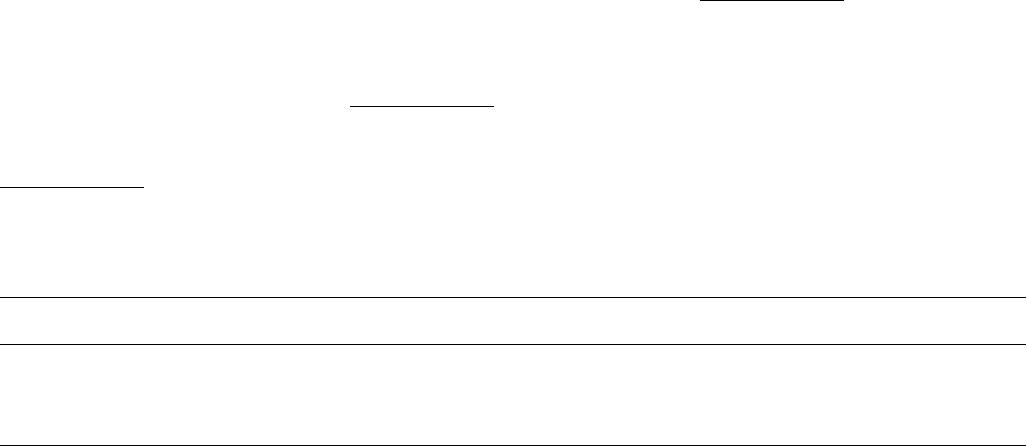

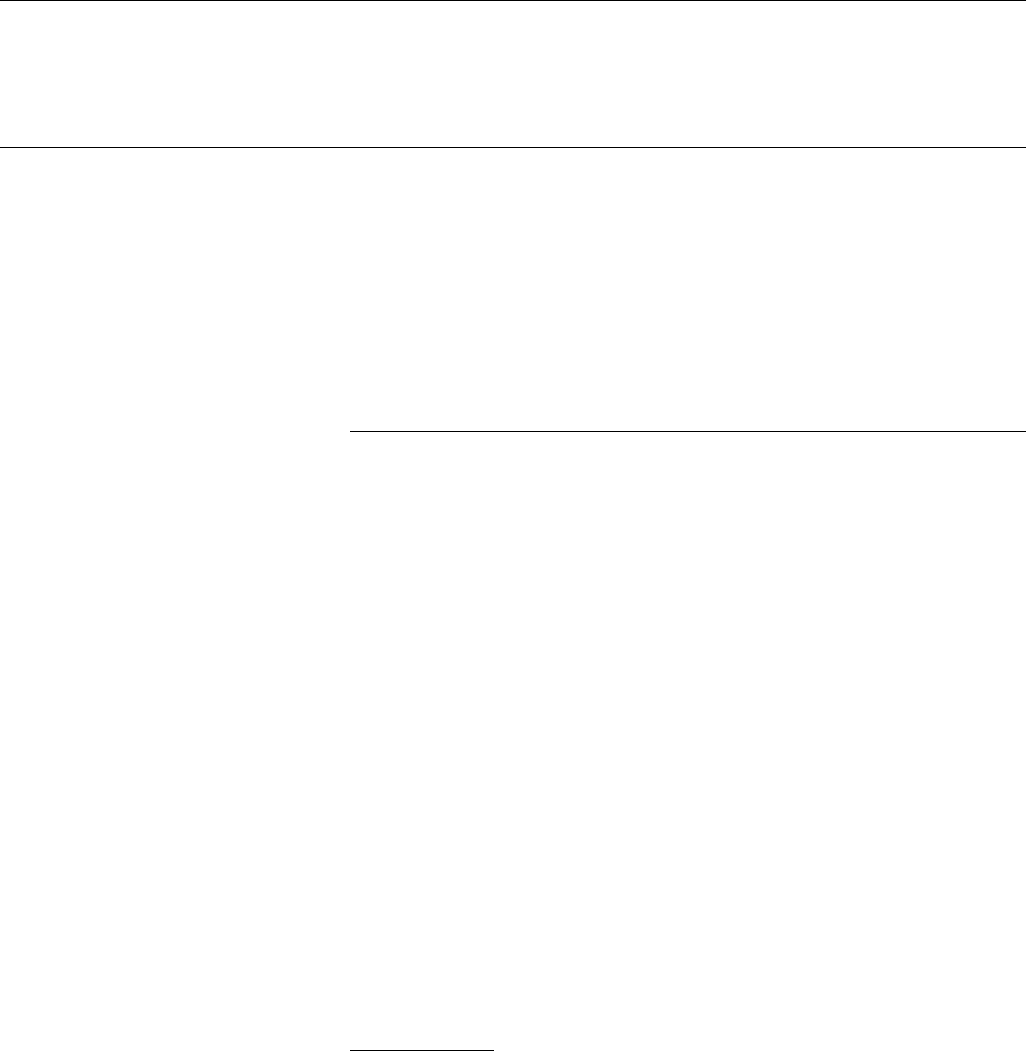

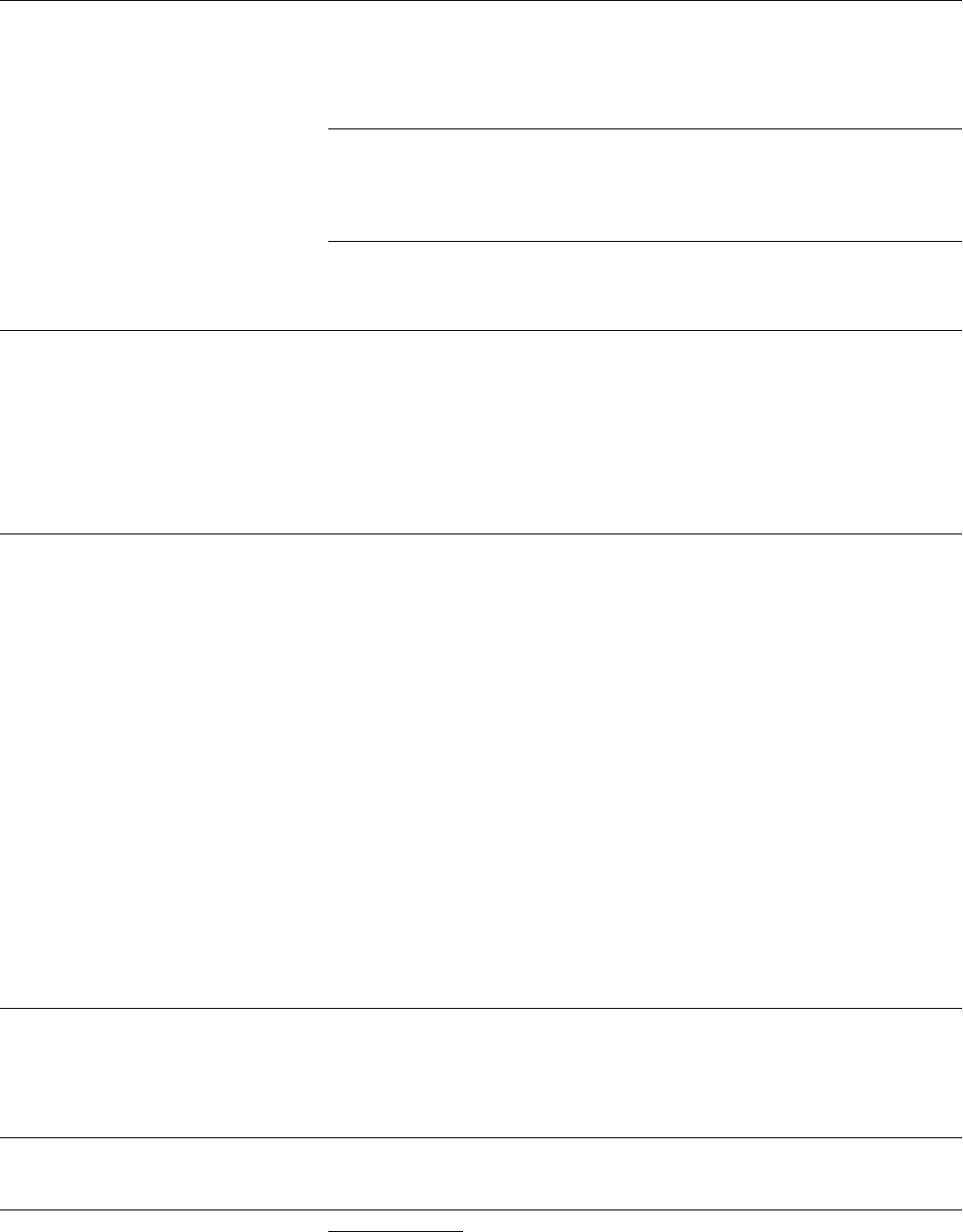

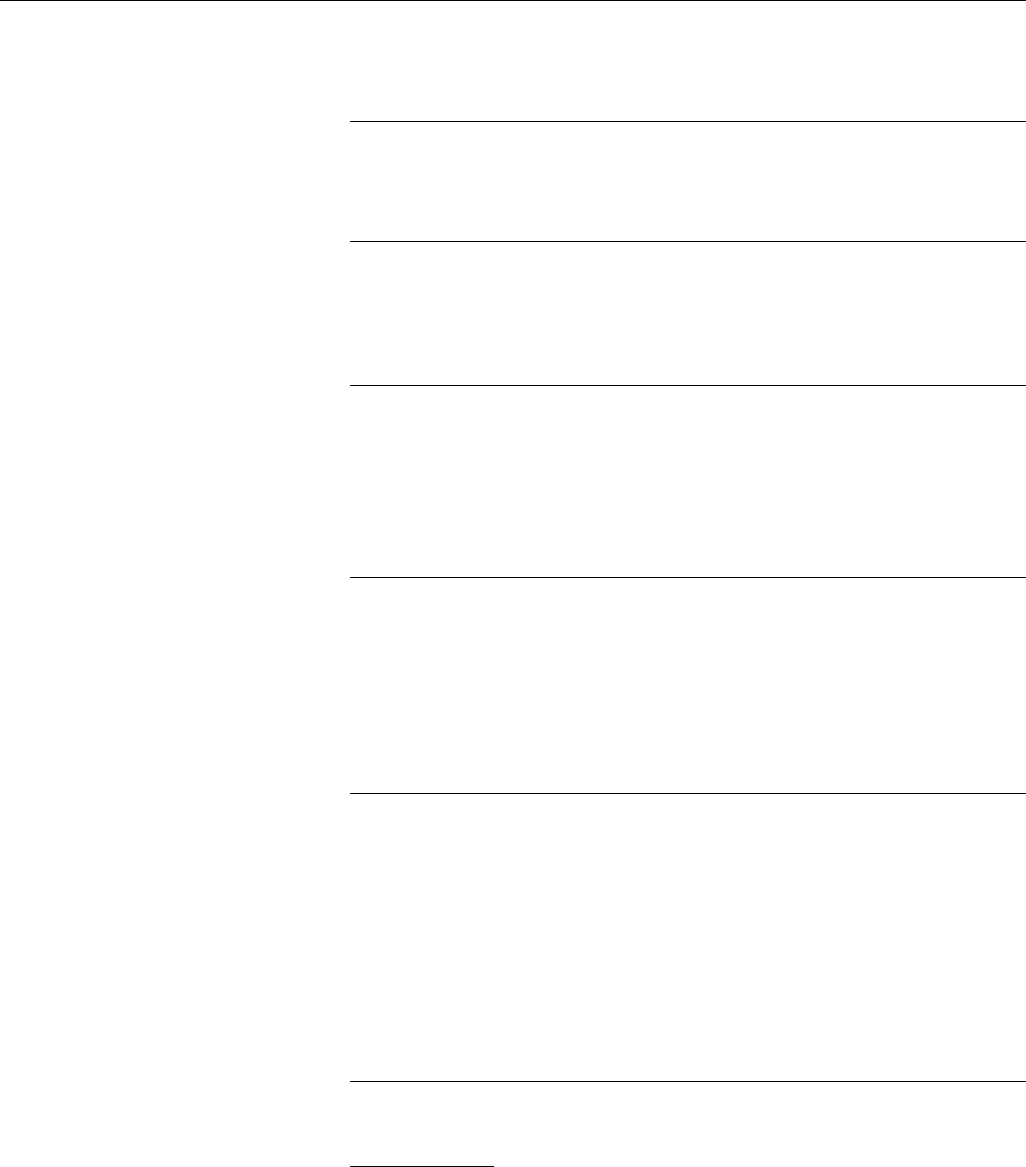

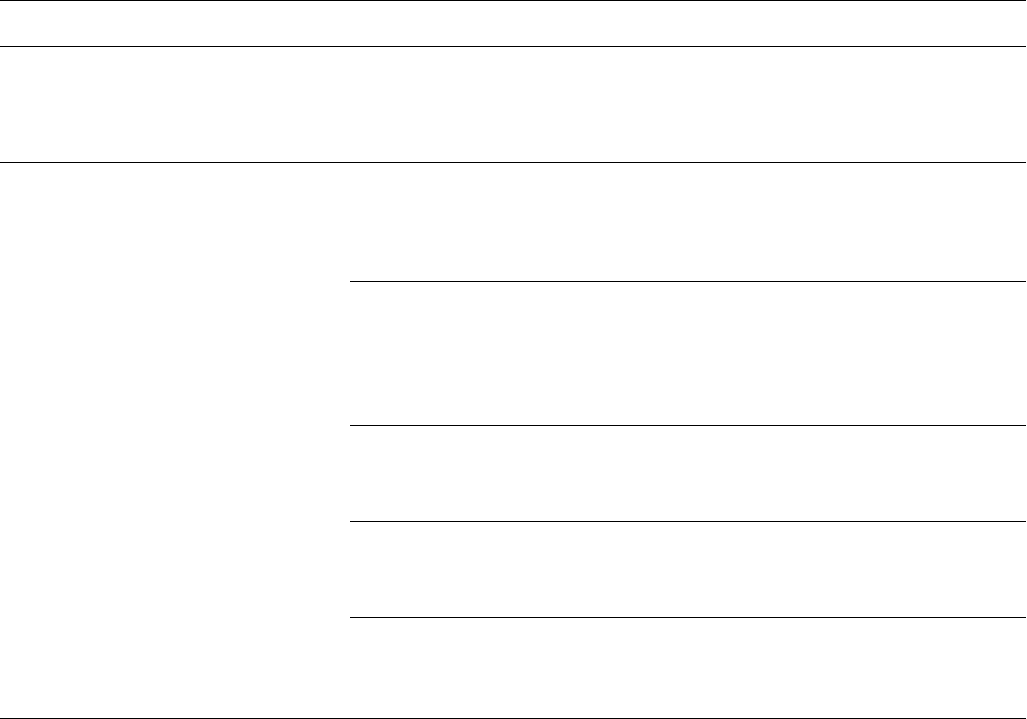

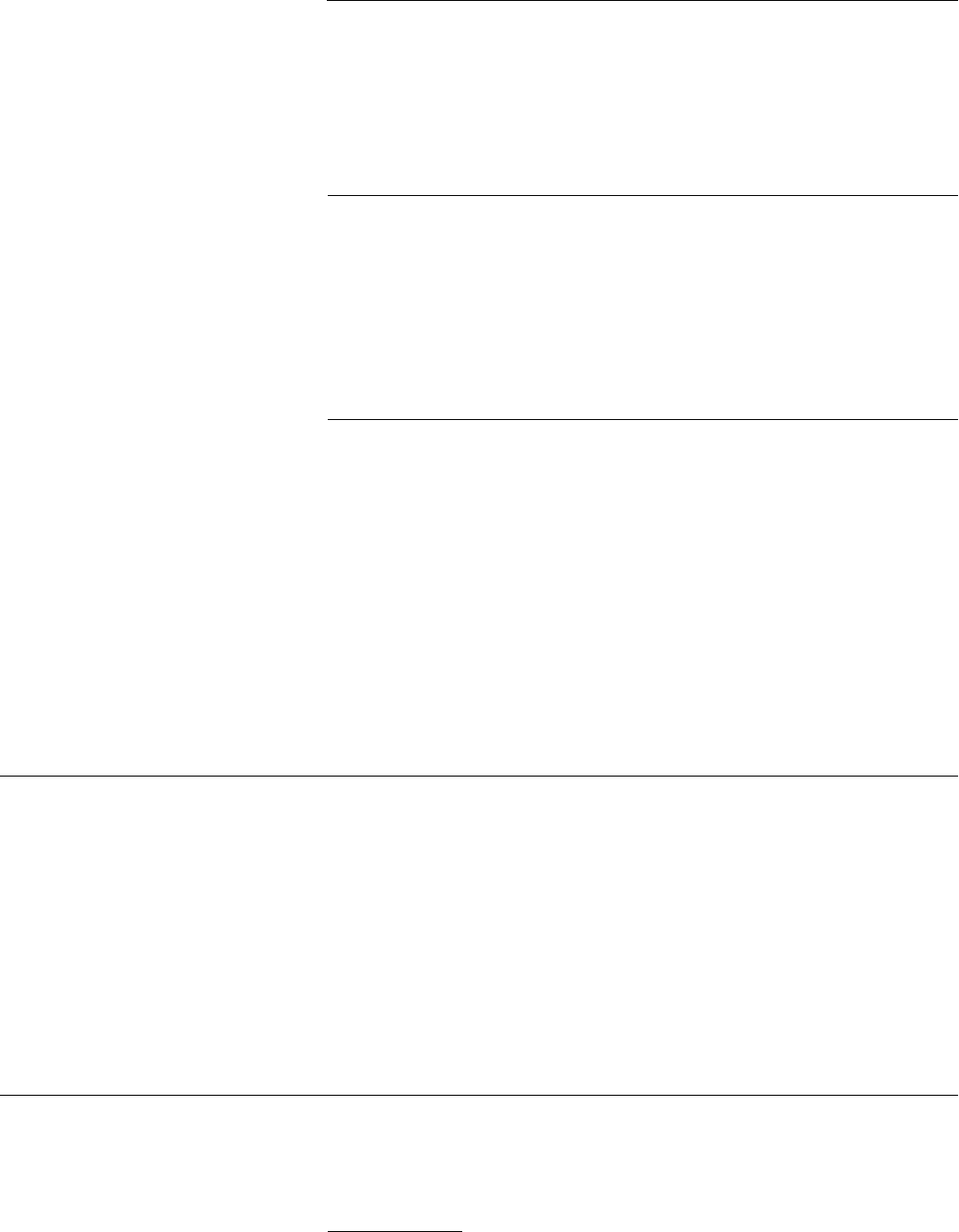

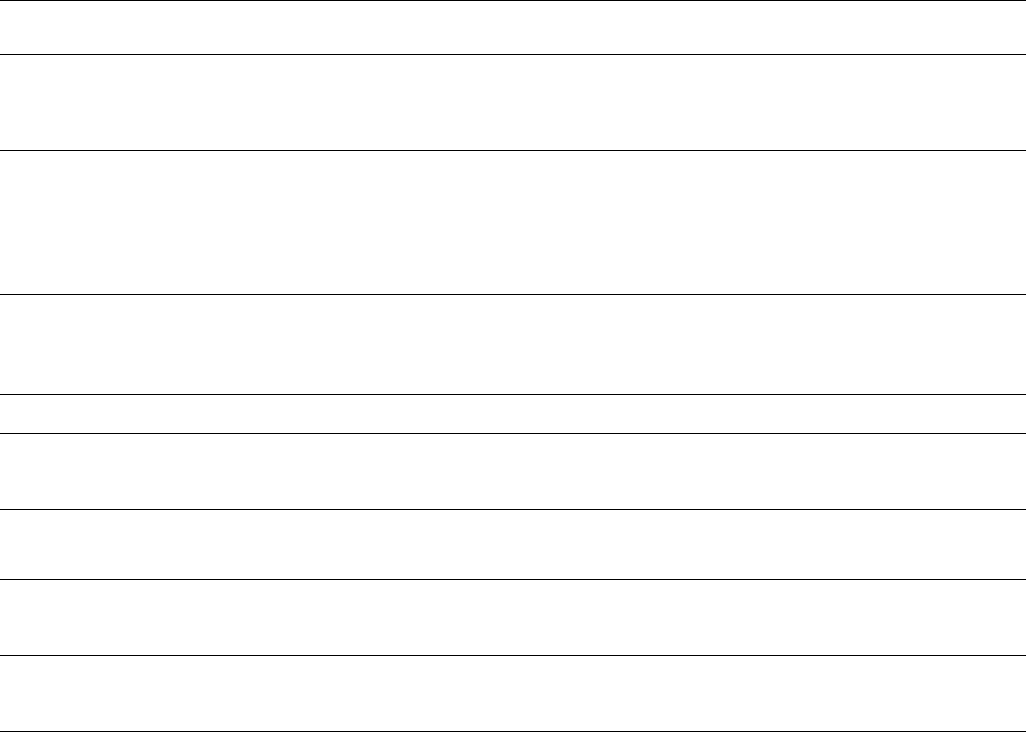

To achieve these ends, primary care

physicians can follow the algorithm,

Physician’s Plan for Older Drivers’ Safety

(PPODS) (see Figure 1.1), which

recommends that physicians:

• Screen for red ags such as medical

illnesses and medications that may

impair driving safety;

• Ask about new-onset impaired

driving behaviors (see Am I a Safe

Driver and How to Help the Older

Driver in the appendices);

• Assess driving-related functional

skills in those patients who are at

increased risk for unsafe driving; for

the functional assessment battery,

Assessment of Driver Related Skills

(ADReS), see Chapter 3;

• Treat any underlying causes of

functional decline;

• Refer patients who require a driving

evaluation and/or adaptive training to

a driver rehabilitation specialist;

• Counsel patients on safe driving

behavior, driving restrictions, driving

cessation, and/or alternate transporta-

tion options as needed; and

• Follow-up with patients who should

adjust their driving to determine if

they have made changes, and evalu-

ate those who stop driving for signs of

depression and social isolation.

While primary care physicians may

be in the best position to perform the

PPODS, other clinicians have a re-

sponsibility to discuss driving with their

patients as well. Ophthalmologists,

neurologists, psychiatrists, physiatrists,

orthopedic surgeons, emergency depart-

ment and trauma center physicians,

and other specialists all treat condi-

tions, prescribe medications, or perform

procedures that may have an impact on

driving skills. When counseling their

patients, physicians may wish to

consult the reference list of medical

conditions in Chapter 9.

In the following chapters, we will guide

you through the PPODS and provide

the tools you need to perform it. Before

we begin, you may wish to review the

AMA’s policy on impaired drivers (see

Figure 1.2).This policy can be applied

to older drivers with medical conditions

that impair their driving skills and

threaten their personal driving safety.

Fact #6: Trafc safety for older

drivers is a growing public

health issue.

Older drivers are the safest drivers as

an age group when using the absolute

number of crashes per 100 licensed

drivers per year.

30

However, the crash

rate per miles driven reveals an increase

at about age 65 to 70 in comparison to

middle-aged drivers.

31

In 2000, 37,409

Americans died in motor vehicle

crashes.

32

Of this number, 6,643 were 65

and older.

33

Accidental injuries are the

seventh leading cause of death among

older people and motor vehicle crashes

are not an uncommon cause.

34

As the

number of older drivers continues to

grow, drivers 65 and older are expected

to account for 16 percent of all crashes

and 25 percent of all fatal crashes.

35

Motor vehicle injuries are the leading

cause of injury-related deaths among

65- to 74-year-olds and are the second

leading cause (after falls) among 75- to

84-year-olds.

36

Compared to other driv-

30. CDC. (1997). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveil-

lance System Survey Data. Atlanta: Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention

31. Ball, K., Owsley, C., Stalvey, B., Roenker, D.

L., & Sloane, M. E. Driving avoidance and

functional impairment in older drivers. Accid

Anal Prev. 30:313–322.

32. NHTSA. FARS. Web-Based Encyclopedia.

www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov.

33. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. (2001).

Fatality Facts: Elderly (as of October 2001).

(Fatality Facts contains an analysis of data from

U.S. Department of Transportation Fatality

Analysis Reporting System.) Arlington, VA:

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

34. Staats, D. O. Preventing injury in older adults.

Geriatrics. 63:12–17.

35. Eberhard, J. Older drivers up close: they aren’t

dangerous. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety

Status Report (Special Issue: Older Drivers).

36(8):1–2.

36. CDC. (1999). 10 Leading Causes of Injury

Deaths, United States, 1999, All Races, Both

Sexes. Ofce of Statistics and Programming,

National Center for Injury Prevention and Con-

trol, Centers for Disease Control and Preven-

tion. Data source: National Center for Health

Statistics Vital Statistics System. Atlanta:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ers, older drivers have a higher fatality

rate per mile driven than any other age

group except drivers under 25.

37

On the

basis of estimated annual travel, the

fatality rate for drivers 85 and older is

9 times higher than the rate for drivers

25 to 69.

38

By age 80, male and female

drivers are 4 and 3.1 times more likely,

respectively, than 20-year-olds to die

as a result of a motor vehicle crash.

39

There is a disproportionately higher rate

of poor outcomes in older drivers, due

in part to chest and head injuries.

40

Old-

er adult pedestrians are also more likely

to be fatally injured at crosswalks.

41

There may be several reasons for this

excess in fatalities. First, some older

drivers are considerably more fragile.

For example, the increased incidence

of osteoporosis, which can lead to

fractures, and/or atherosclerosis of the

aorta which can predispose individuals

to rupture with chest trauma from an

airbag or steering wheel. Fragility begins

to increase at age 60 to 64 and

increases steadily with advancing age.

42

A recent study noted that chronic

conditions are determinants of mortality

and even minor injury.

43

As noted above,

older drivers are also overrepresented in

37. NHTSA. Driver fatality rates, 1975-1999.

Washington, DC: National Highway Trafc

Safety Administration.

38. NHTSA. National Center for Statistics &

Analysis. Trafc Safety Facts 2000: Older

Population. DOT HS 809 328. Washington,

DC: National Highway Trafc Safety

Administration.

39. Evans, L. Risks older drivers face themselves

and threats they pose to other road users.

Int J Epidemiol. 29:315–322.

40. Bauza, G., Lamorte, W. W., Burke, P., &

Hirsch, E. F. High mortality in elderly drivers is

associated with distinct injury patterns: analysis

of 187,869 drivers. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care.

64:304–310.

41. FHWA. (2007). Pedestrian Safety Guide and

Countermeasres. PEDSAFE. 2007. Washington,

DC: Federal Highway Administration. www.

walkinginfo.org/pedsafe/crashstats.cfm. Accessed

November 21, 2007.

42. Li, G., Braver, E., & Chen, L-H. Fragility versus

excessive crash involvement as determinants of

high death rates per vehicle mile of travel for

older drivers. Accid Anal Prev. 35, 227–235.

43. Camiloni, L., Farchi, S., Giorgi Rossi, P., Chini,

F., et al. Mortality in elderly injured patients:

the role of comorbidities. Int J Inj Control Safety

Prom. 15:25–31.

(Continues on page 7)

6 Chapter 1—Safety and the Older Driver With Functional or Medical Impairments: An Overview

Figure 1.1 Physician’s Plan for Older Drivers’ Safety (PPODS)

Is the patient at increased risk for unsafe driving?

Perform initial screen—

• Observe the patient

• Be alert to red ags

¤ Medical conditions

¤ Medications and polypharmacy

¤ Review of systems

¤ Patient’s or family member’s concern/

impaired driving behaviors

At risk

Formally assess function

• Assess Driving Related Skills (ADReS)

¤ Vision

¤ Cognition

¤ Motor and somatosensory skills

Medical interventions

• For diagnosis and

treatment

Counsel and follow up

• Explore alternatives to driving

• Monitor for depression and social isolation

• Adhere to state reporting regulations

Deficit not resolved

Refer to Driver Rehabilitation Specialist:

Is the patient safe to drive?

No Yes

Deficit resolved

Not at risk

Health maintenance

• Successful Aging Tips

• Tips for Safe Driving

• Mature Driving classes

• Periodic follow-up

If screen is positive—

• Ask health risk assessment/social history questions

• Discuss alternatives to driving early in the process

• Gather additional information

7

left-hand-turn collisions, which cause

more injury than more injury than

rear-end collisions.

44

Finally, preliminary

data from a Missouri study of medically

impaired drivers who were in crashes

indicate that the average age of the

vehicle was more than 10 years and the

cars often did not have air bags (personal

communication, Tom Meuser, University

of St. Louis-Missouri). If this latter obser-

vation is a contributing factor, improve-

ment should occur as future cohorts of

aging drivers purchase newer vehicles

with improved crashworthiness.

44. IIHS. (2003). Fatality Facts: Older People as

of November 2002. Arlington, Va: Insurance

Institute for Highway Safety.

Chapter 1—Safety and the Older Driver With Functional or Medical Impairments: An Overview

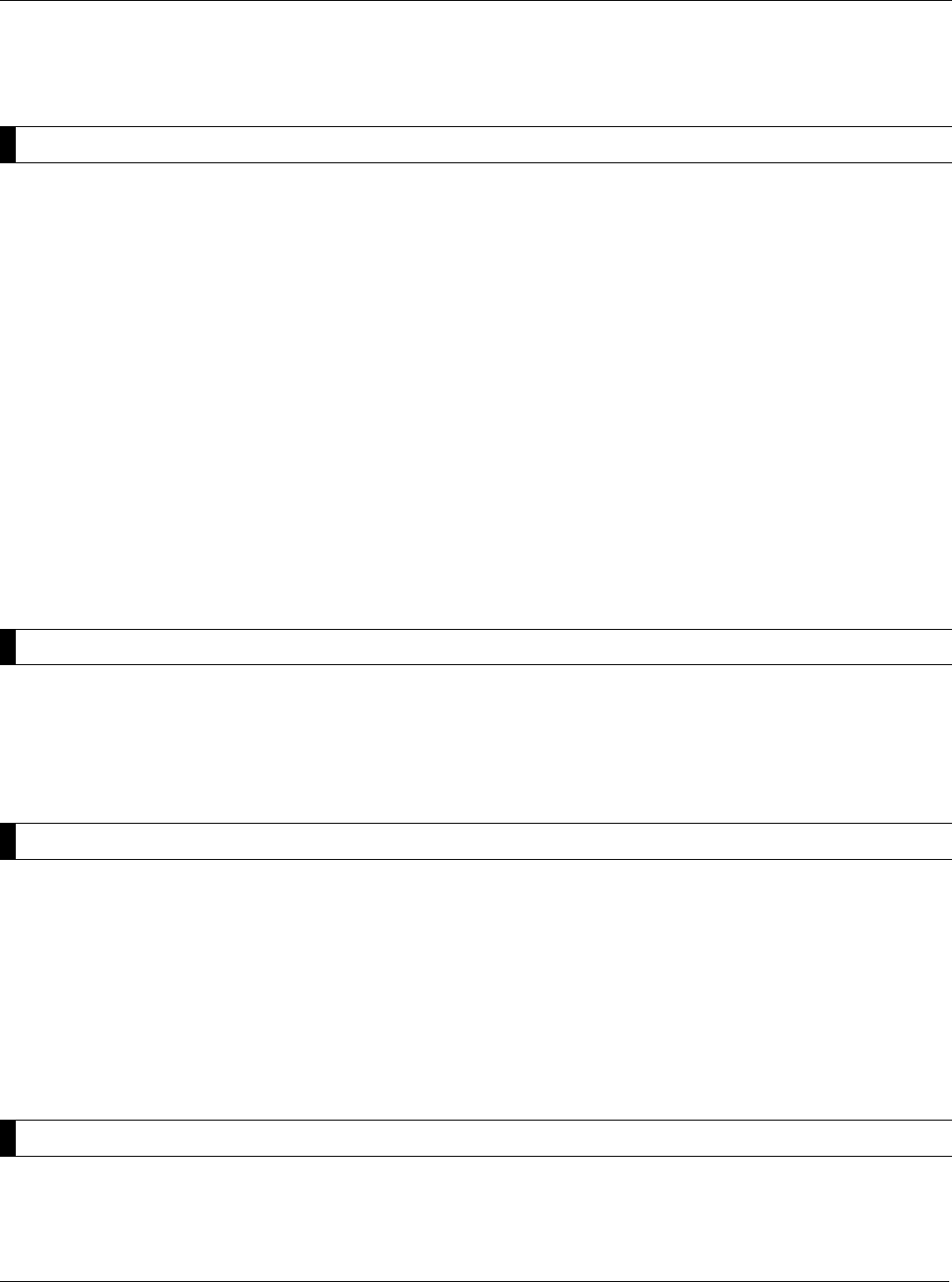

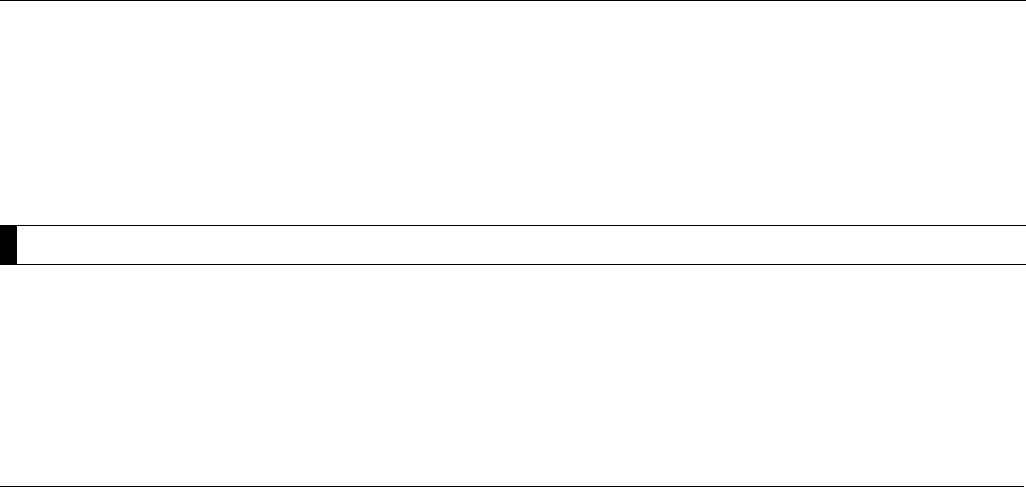

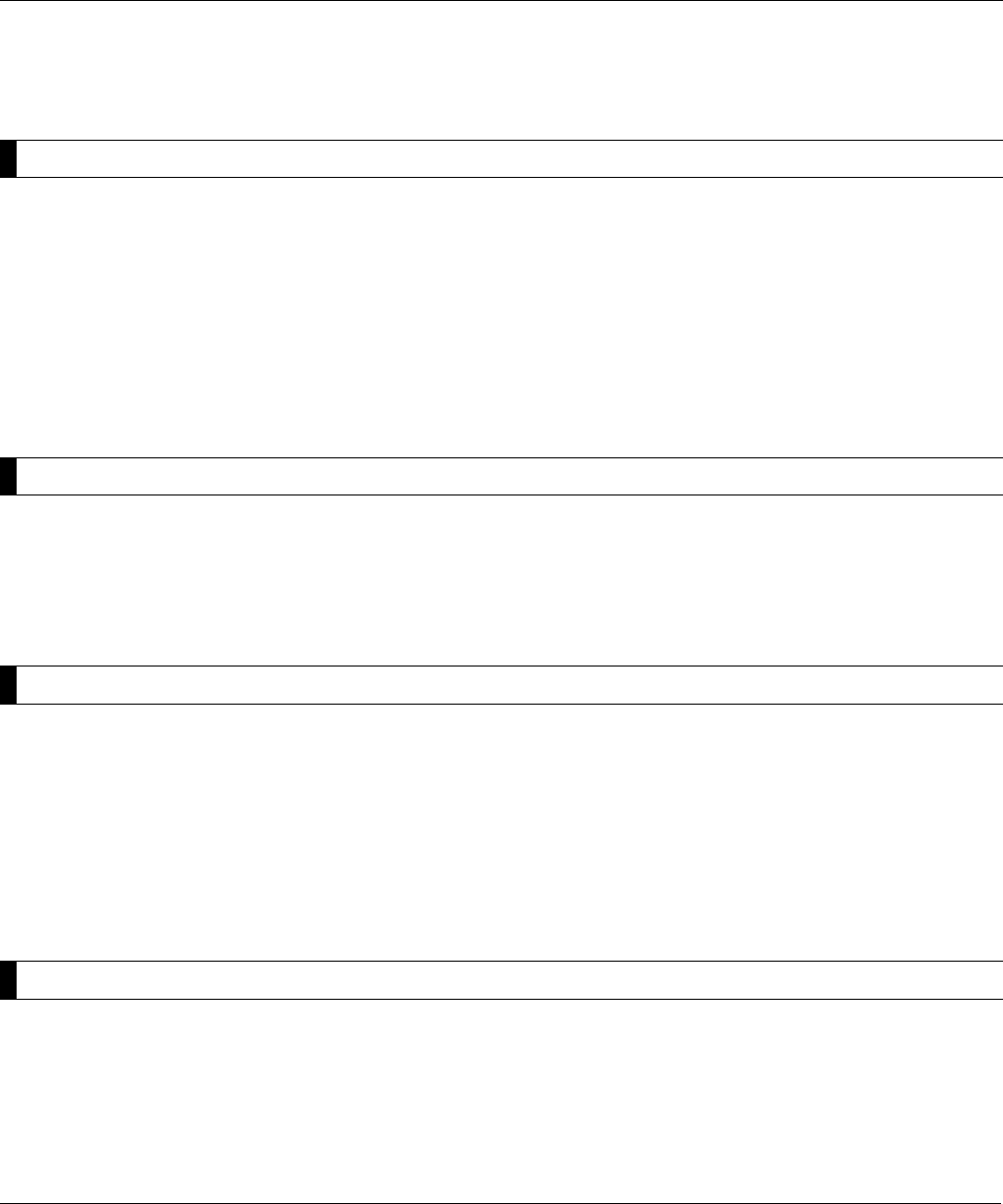

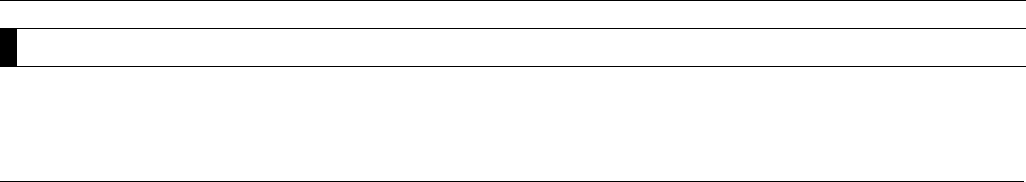

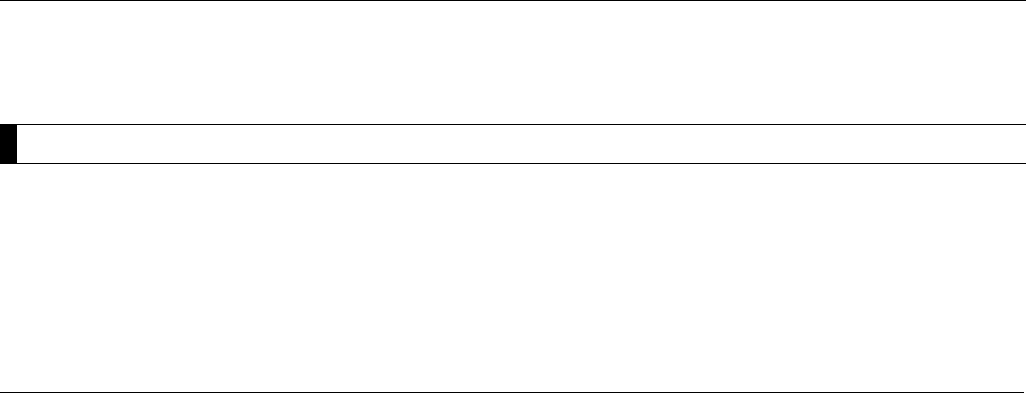

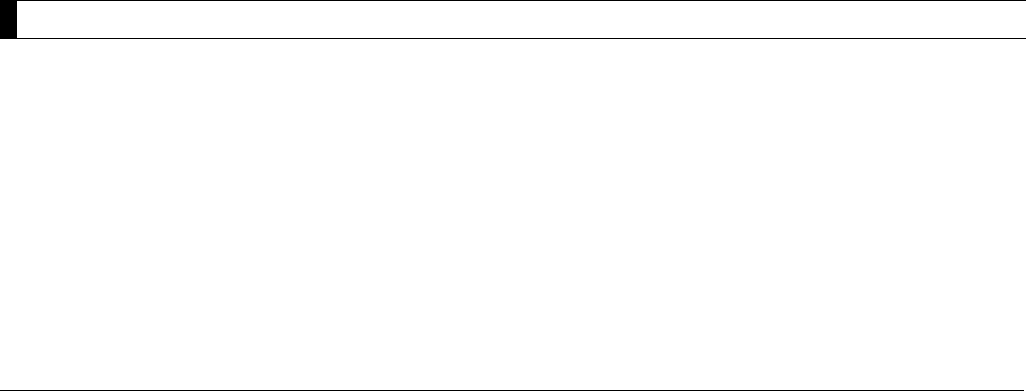

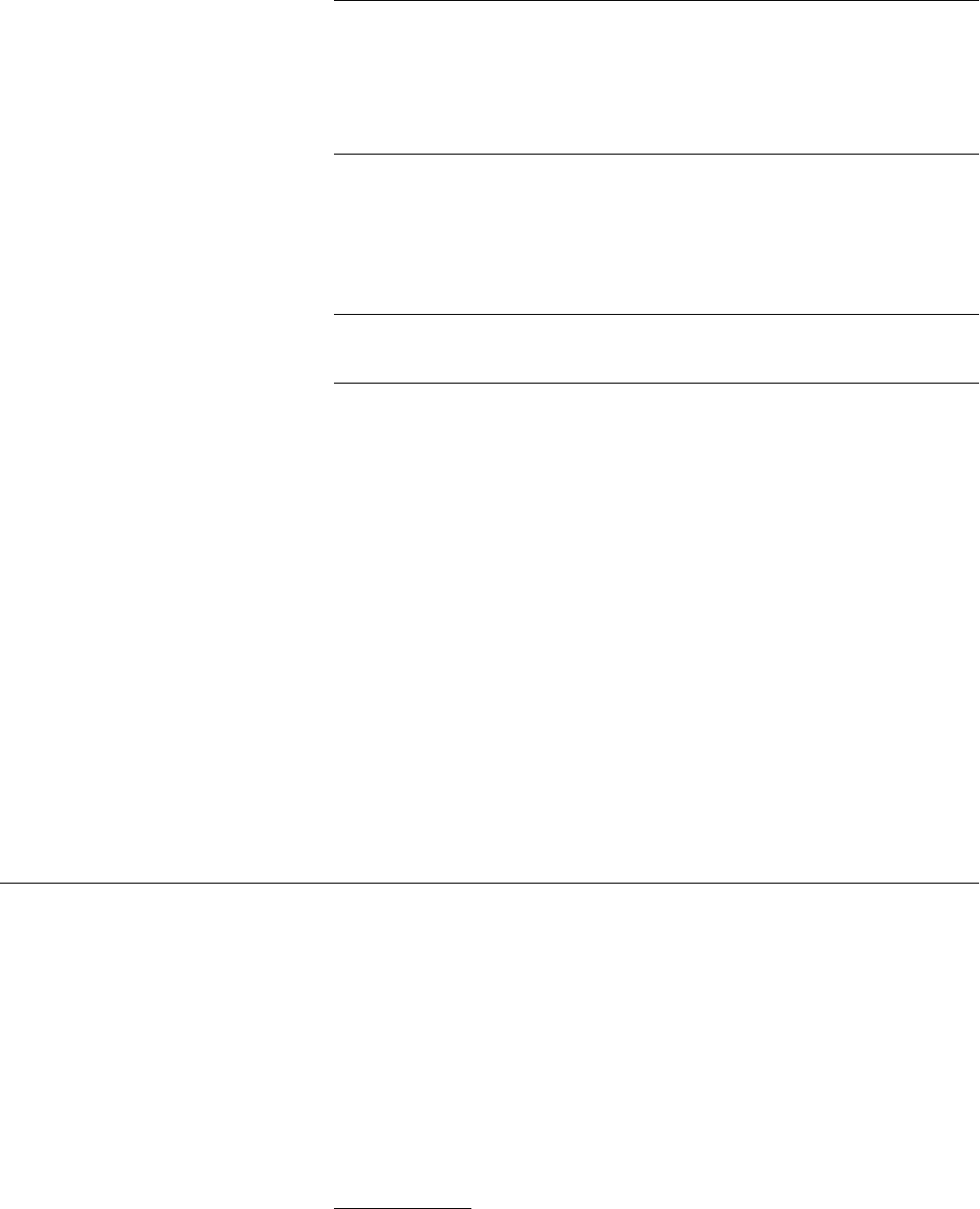

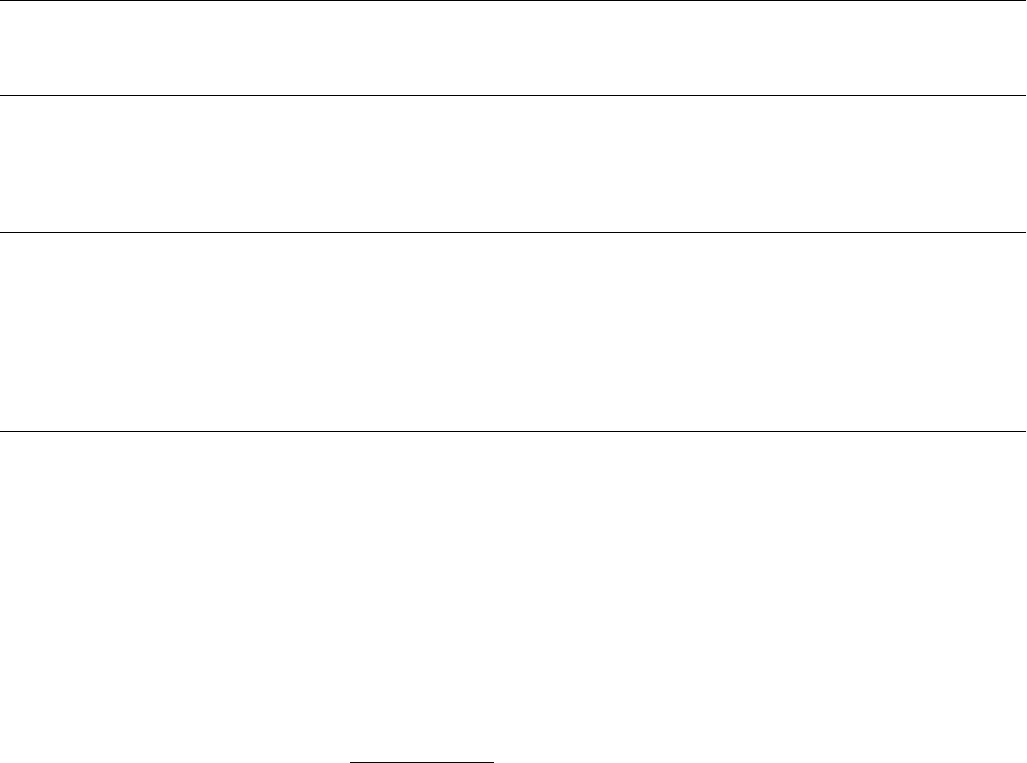

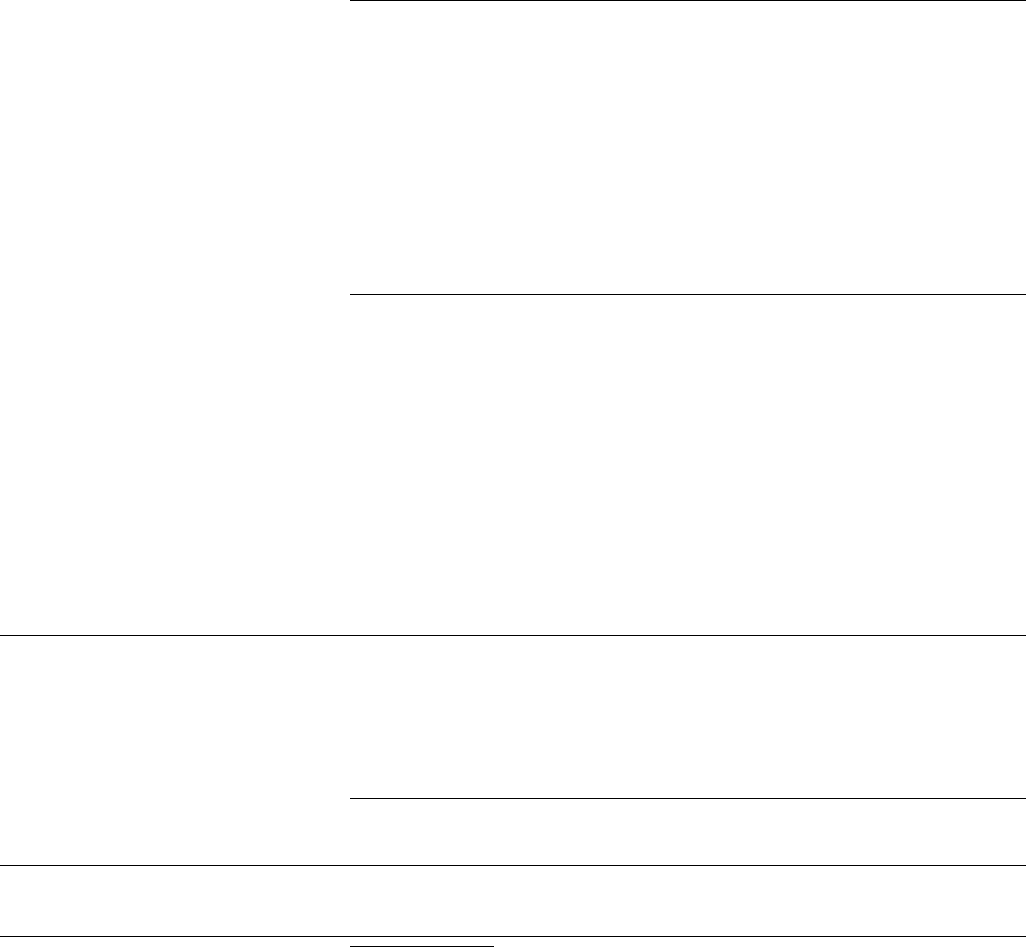

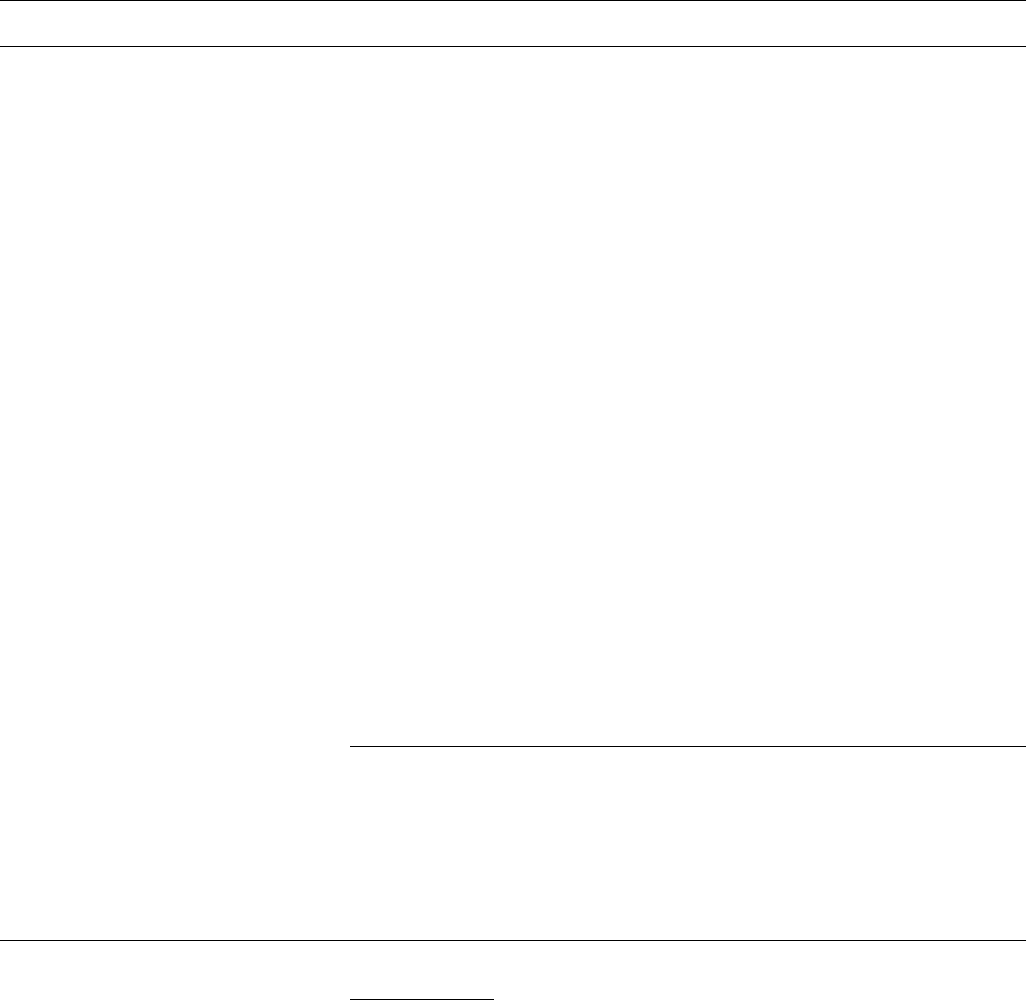

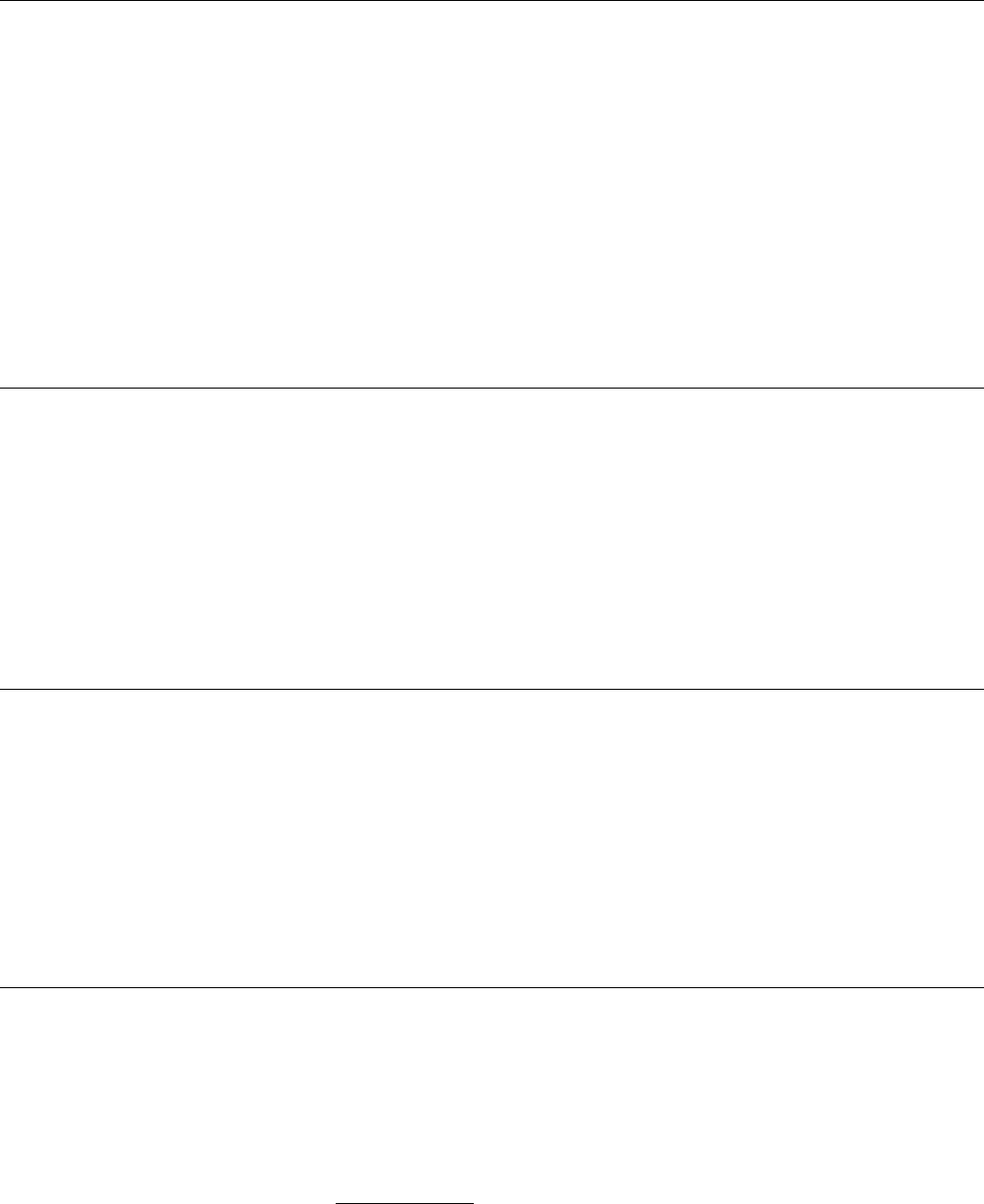

Figure 1.2

AMA ethical opinion

E-2.24 Impaired drivers and their physicians

The purpose of this policy is to articulate physicians’ responsibility to recognize

impairments in patients’ driving ability that pose a strong threat to public safety and

which ultimately may need to be reported to the Department of Motor Vehicles. It

does not address the reporting of medical information for the purpose of punish-

ment or criminal prosecution.

1. Physicians should assess patients’ physical or mental impairments that might

adversely affect driving abilities. Each case must be evaluated individually since

not all impairments may give rise to an obligation on the part of the physician.

Nor may all physicians be in a position to evaluate the extent or the effect of an

impairment (e.g., physicians who treat patients on a short-term basis). In mak-

ing evaluations, physicians should consider the following factors: (a) the physi-

cian must be able to identify and document physical or mental impairments

that clearly relate to the ability to drive; and (b) the driver must pose a clear risk

to public safety.

2. Before reporting, there are a number of initial steps physicians should take.

A tactful but candid discussion with the patient and family about the risks of

driving is of primary importance. Depending on the patient’s medical condition,

the physician may suggest to the patient that he or she seek further treatment,

such as substance abuse treatment or occupational therapy. Physicians also

may encourage the patient and the family to decide on a restricted driving

schedule, such as shorter and fewer trips, driving during non-rush-hour traffic,

daytime driving, and/or driving on slower roadways if these mechanisms would

alleviate the danger posed. Efforts made by physicians to inform patients and

their families, advise them of their options, and negotiate a workable plan may

render reporting unnecessary.

3. Physicians should use their best judgment when determining when to report

impairments that could limit a patient’s ability to drive safely. In situations where

clear evidence of substantial driving impairment implies a strong threat to

patient and public safety, and where the physician’s advice to discontinue driv-

ing privileges is ignored, it is desirable and ethical to notify the Department of

Motor Vehicles.

4. The physician’s role is to report medical conditions that would impair safe driv-

ing as dictated by his or her State’s mandatory reporting laws and standards of

medical practice. The determination of the inability to

drive safely should be made by the State’s Department of Motor Vehicles.

5. Physicians should disclose and explain to their patients this responsibility to

report.

6. Physicians should protect patient confidentiality by ensuring that only the mini-

mal amount of information

is reported and that reasonable security measures are used in handling that

information.

7. Physicians should work with their State medical societies to create statutes

that uphold the best interests of patients and community, and that safeguard

physicians from liability when reporting in good faith. (III, IV, VII) Issued June

2000 based on the report “Impaired Drivers and Their Physicians,” adopted

December 1999.

CHAPTER 2

Is the Patient at

Increased Risk for

Unsafe Driving?

11Chapter 2—Is the Patient at Increased Risk for Unsafe Driving?

Mr. Phillips, a 72-year-old man with

a history of hypertension, congestive

heart failure, type 2 diabetes mel-

litus, macular degeneration, and

osteoarthritis comes to your ofce for

a routine check-up. You notice that

Mr. Phillips has a great deal of trou-

ble walking to the examination room,

is aided by a cane, and has difculty

reading the labels on his medication

bottles, even with his glasses. While

taking a social history, you ask him

if he still drives, and he states that

he takes short trips to run errands,

reach appointments, and meet

weekly with his bridge club.

Mr. Bales, a 60-year-old man with

no signicant past medical history,

presents at the emergency department

with an acute onset of substernal

chest pain. He is diagnosed with

acute myocardial infarction. Follow-

ing an uneventful hospital course, he

is stable and ready to be discharged.

On the day of discharge, he mentions

that he had driven himself to the

emergency department and would

now like to drive himself home, but

cannot nd his parking voucher.

CHAPTER 2

Is the Patient at Increased

Risk for Unsafe Driving?

This chapter discusses the rst steps of

the Physician’s Plan for Older Drivers’

Safety (PPODS). In particular, we

provide a strategy for answering the

question, “Is the patient at increased

risk for unsafe driving?” This part of the

evaluation process includes your clinical

observation, identifying red ags such

medical illnesses and medications that

may impair safe driving, and inquiring

about new onset driving behaviors that

may indicate declining trafc skills.

To answer this question, rst—

Observe the patient

throughout the office visit.

Careful observation is often an impor-

tant step in diagnosis. As you observe

the patient, be alert to:

• Impaired personal care such as poor

hygiene and grooming;

• Impaired ambulation such as difculty

walking or getting into and out of

chairs

• Difculty with visual tasks; and

• Impaired attention, memory, language

expression or comprehension.

In the example above, Mr. Phillips

has difculty walking and reading his

medication labels. This raises a question

as to whether he can operate vehicle

foot pedals properly or see well enough

to drive safely. His physical limitations

would not preclude driving, but may

be indicators that more assessment

is indicated.

Be alert to conditions in the

patient’s medical history,

examine the current list of

medications, and perform

a comprehensive review

of systems.

When you take the patient’s history, be

alert to “red ags,”

45

that is, any medical

condition, medication or symptom that

can affect driving skills, either through

acute effects or chronic functional

decits (see Chapter 9). For example,

Mr. Evans, as described in Chapter 1,

presents with lightheadedness associated

with atrial brillation. This is a red ag,

and he should be counseled to cease

driving until control of heart rate and

symptoms that impair his level of con-

sciousness have resolved. Similarly, Mr.

Bales’ acute myocardial infarction is a

red ag. Prior to discharge from the

hospital, his physician should counsel

him about driving according to the

recommendations in Chapter 9 (see

Figure 2.1).

Mr. Phillips does not have any acute

complaints, but his medical history

identies several conditions that place

him at potential risk for unsafe driving.

His macular degeneration may prevent

him from seeing well enough to drive

safely. His osteoarthritis may make it

difcult to operate vehicle controls or it

may restrict his neck range of motion,

thereby diminishing visual scanning

in trafc. Questions in regard to his

45. Dobbs, B. M. (2005) Medical Conditions and

Driving: A Review of the Literature (1960-

2000). Report # DOT HS 809 690. Wahington,

DC: National Highway Trafc Safety Adminis-

tration. Accessed October 11, 2007.

at www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/research/

Medical_Condition_Driving/pages/TRD.html.

12 Chapter 2—Is the Patient at Increased Risk for Unsafe Driving?

diabetes include: Does he have any

end-organ damage such as sensory neu-

ropathies, chronic cognitive decline, or

uctuations from stroke that may affect

his ability to operate a motor vehicle?

Could any of his medications impair

driving performance?

Most older adults have at least one

chronic medical condition and many

have multiple conditions. The most

common medical conditions in older

adults include arthritis, hypertension,

hearing impairments, heart disease,

cataracts, dizziness, orthopedic impair-

ments, and diabetes.

46

Some of these

conditions have been associated with

driving impairment and will be dis-

cussed in more detail in subsequent

chapters. Additionally, keep in mind

that many prescription and nonpre-

scription medications have the po-

tential to impair driving skills, either

by themselves or in combination with

other drugs. (See Chapter 9 for a more

in-depth discussion on medications and

driving.) Older patients generally take

more medications than their younger

counterparts and are more susceptible

to their central nervous system effects.

Whenever you prescribe one of these

medications or change its dosage, coun-

sel your patient on its potential to affect

driving safety. You may also recommend

that your patient undergo formal

assessment of function (see Chapter 3)

while he/she is taking a new medication

that may cause sedation. Concern may

be heightened if there are documented

difculties in attention or visuospatial

processing speed (e.g., such as the Trails

B test [see Chapters 3 and 4]).

The review of systems can reveal

symptoms that may interfere with the

patient’s driving ability. For example,

loss of consciousness, confusion, falling

sleep while driving, feelings of faintness,

memory loss, visual impairment, and

muscle weakness all have the potential

to endanger the driver.

46. Health United States: 2002; Current Population

Reports, American with Disabilities, p. 70–73.

Figure 2.1

Counseling the driver in the

inpatient setting

When caring for patients in the inpatient

setting, it can be all too easy for physi-

cians to forget about driving. In a survey

of 290 stroke survivors who were inter-

viewed 3 months to 6 years post-stroke,

fewer than 35% reported receiving advice

about driving from their physicians, and

only 13% reported receiving any type of

driving evaluation. While it is possible that

many of these patients suffered such ex-

tensive deficits that both the patient and

physician assumed that it was unlikely for

the patient to drive again, patients should

still receive driving recommendations from

their physician.

Counseling for inpatients may include

recommendations for permanent driving

cessation, temporary driving cessation,

or driving assessment and rehabilita-

tion when the patient’s condition has

stabilized. Such recommendations are

intended to promote the patient’s safety

and, if possible, help the patient regain

his/her driving abilities.

Figure 2.2

Health risk assessment

A health risk assessment is a series of

questions intended to identify potential

health and safety hazards in the patient’s

behaviors, lifestyle, and living environment.

A health risk assessment may include

questions about, but not limited to:

• Physical activity and diet;

• Use of seat belts;

• Presence of smoke detectors and fire

extinguishers in the home;

• Presence of firearms in the home; and

• Episodes of physical or emotional

abuse.

The health risk assessment is tailored to

the individual patient or patient population.

For example, a pediatrician may ask the

patient’s parents about car seats, while a

physician who practices in a warm-climate

area may ask about the use of hats and

sunscreen. Similarly, a physician who sees

older patients may choose to ask about

falls, injuries, and driving.

At times, patients themselves or family

members may raise concerns. If the fam-

ily of your patient asks, “Is he or she safe

to drive?” (or if the patient expresses

concern), identify the reason for the

concern. Has the patient had any recent

crashes or near-crashes, or is he/she los-

ing condence due to declining

functional abilities? Inquiring about

specic driving behaviors may be more

useful than asking global questions

about safety. A list of specic driving

behaviors that could indicate concerns

for safety is listed in the Hartford guide,

“At the Crossroads.”

47

Physicians can

request family members or spouses to

monitor and observe skills in trafc

with full disclosure and permission from

the patient. Another tactic might be

identifying a family member who refuses

to allow other family members such

as the grandchildren to ride with the

patient due to trafc safety concerns.

Please note that age alone is not a red

ag! Unfortunately, the media often

emphasize age when an older driver is

involved in an injurious crash. This

“ageism” is a well-known phenomenon

in our society.

48

While many people

experience a decline in vision, cognition,

or motor skills as they get older, people

age at different rates and experience

functional changes to different degrees.

The focus should be on functional abili-

ties and medical tness-to-drive and

not on age per se.

Inquire about driving during

the social history/health risk

assessment.

If a patient’s presentation and/or the

presence of red ags lead you to suspect

that he/she is potentially at risk for

unsafe driving, the next step is to ask

whether he/she drives. You can do this

by incorporating the following ques-

tions into the social history or health

risk assessment (see Figure 2.2):

47. The Hartford. At the Crossroads. Hartford, CT.

www.thehartford.com/alzheimers/brochure.html.

Accessed December 12, 2007.

48. Nelson, T. (2002). Ageism: Stereotyping and

Prejudice Against Older Persons. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

13Chapter 2—Is the Patient at Increased Risk for Unsafe Driving?

• “How did you get here today?” or

“Do you drive?”; and

• “Are you having any problems while

operating a motor vehicle?”;

• “Have others expressed concern

about your driving?”; and

• “What would you do if you had to

stop driving?”

If your patient drives, then his/her driv-

ing safety should be addressed. For acute

illness, this generally involves counsel-

ing the patient. For example, Mr. Bales

should be counseled to temporarily

cease driving for a certain period of

time after his acute myocardial infarc-

tion (see Chapter 9). If Mr. Phillips is

started on a new medication, he should

be counseled about the side effects and

their potential to impair driving perfor-

mance, if appropriate.

For chronic conditions, on the other

hand, driving safety is addressed by

formally assessing the functions that are

important for driving. This assessment

will be discussed further in the

next chapter.

Please note that some chronic medical

conditions may have both chronic and

acute effects. For example, a patient

with insulin-dependent diabetes may

experience acute episodes of hypogly-

cemia, in addition to having chronic

complications such as diabetic retinopa-

thy and/or peripheral neuropathy.

In this case, the physician should

counsel the patient to avoid driving

until acute episodes of hypoglycemia

are under control and to keep candy

or glucose tablets within reach in the

car at all times. The physician should

also recommend formal assessment of

function if the patient shows any signs

of chronic functional decline. (See

Chapter 9 for the full recommendation

on diabetes and driving.)

If your patient does not drive, you may

wish to ask if he/she ever drove, and if

so, what the reason was for stopping. If

your patient voluntarily stopped driving

due to medical reasons that are poten-

tially treatable, you may be able to

help her or him return to safe driving.

In this case, formal assessment of

function can be performed to identify

specic areas of concern and serve as

a baseline to monitor the patient’s

improvement with treatment. Referral

to a driver rehabilitation specialist in

these cases is strongly encouraged (see

Chapter 5).

Gather additional information.

To gain a better sense of your patient as

a driver, ask questions specic to driving.

The answers can help you determine the

level of intervention needed.

If a collateral source such as a family

member is available at the appointment

or bedside, consider addressing your

questions to both the patient and the

collateral source with the patient’s

permission. If this individual has had

the opportunity to observe the patient’s

driving, his/her feedback may be

valuable.

Questions to ask the patient and/or

family member:

• “How much do you drive?” (or

“How much does [patient] drive?”)

• “Do you have any problems when you

drive?” (Ask specically about day

and night vision, ease of operating

the steering wheel and foot pedals,

confusion, and delayed reaction to

trafc signs and situations.)

• “Do you think you are a safe driver?”

• “Do you ever get lost while driving?”

• “Have you received any trafc viola-

tions or warnings in the past two years?”

• “Have you had any near-crashes or

crashes in the past two years?”

Understand your patient’s

mobility needs.

At this time you can also ask about your

patient’s mobility needs and encourage

him/her to begin exploring alternative

transportation options before it be-

comes imperative to stop driving. Even

if alternative transportation options

are not needed at this point, it is wise

for the patient to plan ahead in case it

ever becomes necessary.

Some questions you can use to initiate

this conversation include:

• “How do you usually get around?”

• “If your car ever broke down, how

would you get around? Is there any-

one who can give you a ride? Can you

use a public train or bus? Does your

community offer a shuttle service or

volunteer driver service?”

Encourage your patients to plan a safety

net of transportation options. You might

want to say, “Mobility is very impor-

tant for your physical and emotional

health. If you were ever unable to drive

for any reason, I’d want to be certain

that you could still make it to your ap-

pointments, pick up your medications,

go grocery shopping, and visit your

friends.”

Sources for educational materials are

listed in Appendix B like the Hart-